How Should Organized Medicine Respond to Physician-Assisted Death?

Abstract

Both proponents and opponents agree that wider access to high-quality palliative care and physician-patient communication about end-of-life options is the right response to the growing patient demand for control over the end of one’s days. This is the third in a series of articles on physician-assisted death.

“For some physicians, the sacredness of ministering to a terminally ill or dying patient and the duty not to abandon the patient preclude the possibility of supporting patients in hastening their death. For others, not to provide a prescription for lethal medication in response to a patient’s sincere request violates that same commitment and duty.” —From a 2018 report by the AMA Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. (The report was not adopted by the House of Delegates)

In November last year, the AMA debated the second iteration of a report by the AMA’s Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs (CEJA), which stated again that U.S. physicians come to the fraught issue of physician-assisted suicide (PAS) or physician-aid-in-dying (PAD) with “irreducible differences of opinion.”

Debate about PAS/PAD at the AMA and in other venues has shown that divisions over the issue are, indeed, irreducible: opponents and proponents alike appeal to fundamental tenets of the medical profession—either the injunction to “do no harm” and to extend life or to honor patient autonomy and to diminish suffering.

The CEJA report, which was not adopted by the House of Delegates, asserted that the Code of Medical Ethics, as currently written, encompasses both positions—on the one hand, it asserts that “physician-assisted suicide is fundamentally incompatible with the physician’s role as healer,” while on the other hand, it also preserves (in the so-called “conscience code”—Section 1.1.7) the right of physicians to practice according to their conscience in states where PAS/PAD is legal.

It was a difficult needle to thread. That the House of Delegates did not adopt the CEJA report is not surprising; CEJA renders opinions on some of the most difficult issues in medicine, and the council’s reports often go through several iterations before being accepted. But PAS/PAD appears to be a uniquely fraught topic engaging the most fundamental questions of what it means to be a doctor. Even the term is hotly debated, with proponents insisting that patients with terminal illness seeking to end their lives with medical assistance should not be conflated with individuals who are suicidal when they have years of life yet to live. (This article uses PAS/PAD interchangeably.)

Is the Slope Always Slippery?

Among the prominent concerns about physician-assisted death (PAD) is the “slippery slope,” the possibility that it will be extended to people whose illnesses are not terminal, including those with severe mental illness.

But cannot the stakeholders in this issue—especially organized medicine—build “guardrails” to prevent that from occurring? Is the slope always slippery?

Proponents of PAD in states where it is legal insist that the actual experience suggests that those concerns are unfounded. “I think there is enough accumulated experience in the states and other jurisdictions in which the practice of PAD is legally permitted to establish that the ‘slippery slope’ has not emerged nor does it appear to be emerging,” said Oregon psychiatrist David Pollack, M.D.

Oregon enacted the Death With Dignity Act, in 1997, the first jurisdiction to legalize PAD. “The safeguards in the legislation or regulations in these jurisdictions have proven to be adequate to prevent an ever-growing approval of requests for PAD for inappropriate or excluded reasons/criteria.”

From a logical perspective, the slippery slope is not inevitable, said past APA President and ethics expert Paul Appelbaum, M.D. “Just because a policy or practice moves in a particular direction doesn’t mean that it will necessarily continue moving in that direction. For example, policies to make it harder for people who shouldn’t own firearms to purchase them, such as universal background checks (as some states have implemented), are not going to lead to a ban on anyone owning firearms.”

Nevertheless, Appelbaum said that there is momentum behind expanding PAD. “Just because a policy is not compelled to continue moving in a given direction doesn’t mean that in any given case it won’t. Sometimes initial steps toward a particular end make it more likely—even if not inevitable—that policy will continue to evolve in that direction. I think that’s the case for PAD. Does adoption of PAD for terminal conditions necessarily lead to its extension to nonterminal, including psychiatric, disorders? No, I don’t think so. Indeed, the experience in the United States to date suggests that at the very least it doesn’t do so quickly.

“But I still think that adoption of PAD for terminal conditions in the U.S. will make it much more likely that we will see PAD for nonterminal disorders,” he said. “There are several reasons for this—first implementation of PAD will desensitize policymakers, physicians, and the public to the practice of physicians giving their patients the means to end their lives or doing so directly; second, to the extent that PAD is justified on the basis of patient autonomy in the face of untreatable suffering, it is difficult to argue from an ethical perspective that only terminal patients have the right to exercise such autonomy. Finally, legally, implementation of PAD raises equal-protection issues related to affording a right to one group that is withheld from another (arguably similarly situated) group.”

In comments at the House of Delegates, psychiatrist Jim Sabin, M.D., the chair of CEJA, cited the potentially fractious nature of the subject. “This has been a long slog,” he continued. “The debate has been civil, thoughtful, and respectful on a topic that, if not handled well, could split the association.”

A Return to ‘Caring Over Curing’

How can organized medicine respond to a challenge that so deeply divides physicians? How can it answer the growing movement for patient autonomy and the demand—as reflected in the legalization of PAS/PAD in six states and the District of Columbia—for greater patient control over the end of one’s days? And what about concerns around the “slippery slope,” that the practice could evolve, as it has in some countries, beyond patients with terminal conditions (see sidebar)?

If there is one area of common ground shared by physicians on all sides, it is the need for wider access to palliative care and greater communication between physicians and patients about options for end-of-life care.

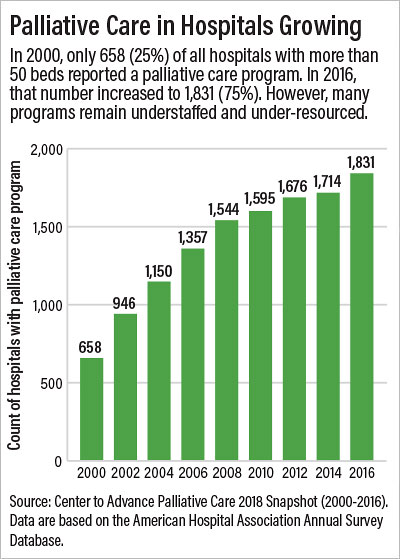

The 2018 Palliative Care Growth Snapshot by the Center to Advance Palliative Care reported that between 2000 and 2016, the number of hospitals with palliative care programs tripled (see chart). Yet availability is highly variable by geography and hospital size. Even in hospitals that report having palliative care services, only a small fraction of the patients that could benefit use the service, the center reported.

In comments to Psychiatric News, Joseph Rotella, M.D., chief medical officer of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAHPM), emphasized a point that both opponents and proponents of PAS/PAD would affirm: “No one should ever have to consider PAD because they cannot access palliative care.”

Rotella said the discussion about what quality of life means to people nearing the end of life presents an opportunity to advocate for palliative care and hospice. “Suffering near the end of life arises from many sources including loss of sense of self, loss of control, fear of the future, and/or fear of being a burden upon others, as well as refractory physical and nonphysical symptoms,” he said. “For the vast majority of patients living with terminal illness, expert palliative care and hospice can help them maintain a quality of life they consider acceptable.”

He continued, “About half of dying patients never enter hospice care, and many get it only for the last days or few weeks of life,” he said. “A barrier to earlier access to hospice care is reluctance by patients, family members, and physicians to have the conversation about prognosis and adjusting goals of care when the illness is advancing. Other forms of palliative care are appropriate at any stage of serious illness and can be provided alongside active treatments for the underlying illness. Most hospitals have inpatient palliative care teams.”

Rotella added that access to palliative care is more limited in outpatient settings, primarily due to a lack of funding. “We’re seeing an expansion of community-based palliative care services as more payers are covering it as a benefit, but current reimbursement under traditional Medicare remains insufficient,” he said.

To address that barrier, AAHPM has proposed an alternative payment model for community-based palliative care that was recommended last year by the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee for limited-scale testing by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Beyond providing better palliative care and making it more widely accessible, Daniel Sulmasy, M.D., Ph.D., senior research scholar at Georgetown University’s Kennedy Institute of Ethics, argues for a return to what the bioethicist Daniel Callahan 30 years ago called the priority of “caring over curing.” He reminds physicians that the same Hippocrates who urged doctors to “do no harm” also cautioned against physicians attempting to treat patients who are “overmastered by disease.”

An opponent of PAS, Sulmasy said it is “the wrong answer” to the right question: How can medicine respond to people’s concerns about dying a technological death?

“The power of modern medicine is not the power to relieve humans of the human condition. We don’t make humans immortal. Our charge is to use life-extending technology wisely. I don’t want to deny people access to chemotherapy that will allow them to live longer with a good quality of life. But I also know there are countless cases in which patients continue to get chemo when it has long outlived its usefulness, when they wind up on ventilators when they probably never should have been started on one to begin with.”

He added, “That’s not good medicine, and the answer to that problem is to stop using treatments that are more burdensome than beneficial, to treat symptoms, and to provide hospice and palliative care when appropriate. Then we can accompany patients through their last days, even as the bonds that keep us together are dissolving.”

Sulmasy added, “At this stage, we are recognizing that they are overmastered by disease, and we are letting them go.” ■