Common Dementia Screening Tests Often Misclassify Patients

Abstract

The findings might help guide physicians to the most appropriate cognitive tests for their patients based on age, ethnicity, and education level.

Brief cognitive tests that take a few minutes to complete can be useful for screening patients for dementia in busy settings. But, new evidence suggests that such brevity may come at the cost of accuracy.

In a study published November 28, 2018, in Neurology: Clinical Practice, researchers examined the error rates of three commonly used cognitive screening tools: the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), which tests memory skills including proper orientation of time and place; the Memory Impairment Screen (MIS), which tests the ability to remember words; and Animal Naming (AN), a verbal fluency test that involves naming as many animals as possible in 60 seconds. They found about a third of the patients who were screened for dementia by at least one of the three short cognitive assessments were misclassified.

“Our study found that all three tests often give incorrect results that may wrongly conclude that a person does or does not have dementia,” study author David Llewellyn, Ph.D., a senior research fellow at the University of Exeter Medical School, said in a press release. “Each test has a different pattern of biases, so people are more likely to be misclassified by one test than another depending on factors such as their age, education, and ethnicity.”

The study authors hope that the findings might help guide physicians to the most appropriate cognitive tests for their patients.

Llewellyn and colleagues analyzed data from 824 older adults (aged 70 and older) who had participated in a population-based study looking at risk factors for dementia. All participants received a three- to four-hour neuropsychological exam. A panel of experts then used the neuropsychological data to diagnose the participants’ dementia status. The comprehensive exam included the MMSE, MIS, and AN; this enabled the investigators to see how the results of the brief screening tests compared with the final diagnosis.

Of the 824 participants, 291 (35.3 percent) were diagnosed with dementia. The researchers found that the MMSE, MIS, and AN misclassified 21, 16, and 14 percent of the participants, respectively. The study revealed that 35.7 percent of the participants were misclassified by at least one assessment, 13.4 percent were misclassified by at least two, and 1.7 percent were misclassified by all three.

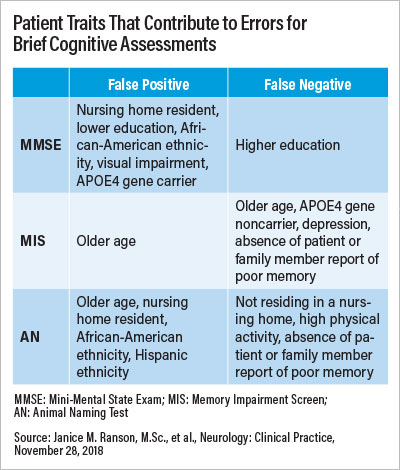

The MMSE errors were overwhelmingly false-positives (that is, a patient without dementia was screened as having dementia), whereas the MIS and AN were more evenly split between false-positives and false-negatives (a patient with dementia being screened as not having dementia).

The researchers identified multiple patient characteristics that contributed to a risk of being misclassified by these tests, though most were specific to one or two of the assessments. For example, African Americans were more likely to be mischaracterized by the MMSE, people with depression were more likely to be mischaracterized by the MIS, and people in nursing homes were more likely to be misclassified by the AN. People with less education and those with heart problems were more likely to be misclassified by both the MMSE and AN.

The study findings also revealed that stroke, which has been previously reported to affect cognitive screening accuracy, did not increase the risk of misclassification in any three of the studied tests.

“Currently, there is not strong evidence to suggest any one particular cognitive test is right for everyone,” said lead study author Janice Ranson, a Ph.D. student in Llewellyn’s lab. She told Psychiatric News that the research group is now using information from the study to find practical ways to improve the accuracy of these cognitive assessments.

In the meantime, she said that knowing which patient variables can influence test results can guide physicians to pick the measurement with the least risk of bias. Or, if test options are limited, physicians can adjust the cutoff scores used to delineate probable dementia versus no dementia for the test. Though the standard cutoff scores of each test are based on clinical consensus, they can be adjusted to factor in such factors as less formal education, she explained.

“It is also important to note that the tests should be only one part of an initial assessment,” Ranson said. “They need to be interpreted alongside a full history, and consideration of any symptoms and difficulties with everyday life, including information from a close family member if available.”

This study was supported by The Alan Turing Institute, Halpin Trust, Mary Kinross Charitable Trust, and National Institute for Health Research. ■

An abstract of “Predictors of Dementia Misclassification When Using Brief Cognitive Assessments” can be accessed here.