Co-Occurring Mental Illnesses May Be More Pervasive Than Previously Thought

Abstract

An analysis of medical data from nearly 6 million Danes also found that in most cases, random chance may dictate which disorder people with co-occurring illnesses will develop first.

Using the robust medical data available in Danish health registries, a team of researchers has developed the most comprehensive map of psychiatric comorbidity (the occurrence of more than one mental illness in an individual) to date.

The notion that a patient can have multiple mental illnesses is not new. Research has shown that similar disorders such as depression and anxiety often co-occur, due to both genetic and environmental factors. However, this new study, published January 16 in JAMA Psychiatry, has taken this knowledge to the next level.

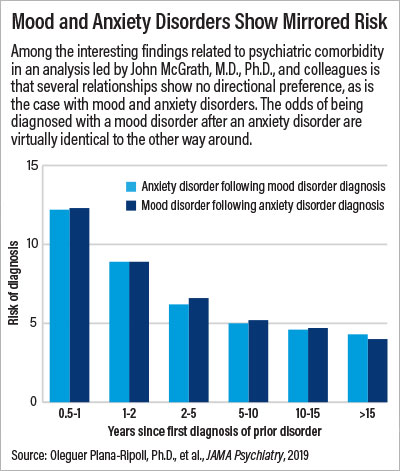

The researchers found that psychiatric comorbidity is more widespread than previously appreciated and is not restricted to closely related psychiatric disorders. In addition, the study found psychiatric comorbidity is often bidirectional; for example, the risk of being diagnosed with major depression after an anxiety disorder is about the same as the risk of being diagnosed with an anxiety disorder after being diagnosed with depression.

“We wanted to provide clinicians, researchers, and patients with the most detailed atlas possible about which psychiatric disorders might occur together,” said senior study author John McGrath, M.D., Ph.D., the Niels Bohr Professor at the National Centre for Register-based Research at Aarhus University in Denmark. “We have a good roadmap now, but we wanted to create the ‘Google streetmap’ version.”

McGrath and his colleagues combed the health registry data of all individuals born in Denmark who resided in the country between 2000 and 2016; this encompassed almost 6 million children and adults and about 84 million years of medical data. They checked for all psychiatric diagnoses, but rather than focus on individual disorders, they grouped mental disorders into 10 categories, as described in ICD-10: behavioral disorders, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; developmental disorders, such as autism; mood disorders, such as depression; neurotic disorders, such as anxiety; organic disorders, such as dementia; eating disorders; intellectual disability; personality disorders; schizophrenia; and substance use disorders. Next, the researchers calculated the risks of an individual with one type of disorder getting a second mental illness diagnosis within 15 years.

They found that comorbidity was pervasive, with some categories of disorders having exceptionally strong odds of occurring together. For example, compared with an individual not diagnosed with a mental disorder, an individual diagnosed with a mood disorder was 30 times more likely to be diagnosed later with a personality disorder or a developmental disorder, and 20 times more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia or a substance use disorder. The younger the age a person was at the time of the first diagnosis, the greater his or her risk of a second diagnosis.

The risk of the second diagnosis was also higher within the first six months after the first diagnosis, which McGrath attributed in part “to doctors doing a thorough job.” A patient comes in and receives a psychiatric diagnosis, which raises the doctor’s attention to other possible symptoms, which may lead to a second diagnosis at a follow-up visit. Therefore, McGrath explained, it is possible that the patient had already developed both disorders, and it just took a little time to uncover both. McGrath added that the risk stayed high for 15 years, though.

Another new discovery from this analysis was that many instances of psychiatric comorbidity were bidirectional. “In some cases, like mood disorders and neurotic disorders, it was startling how similar the risks were of getting one or the other first,” McGrath said. “This is a signal that there are shared genetic risks for these disorders, and that which one manifests first might be purely chance.”

Steven Hyman, M.D., director of the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at the Broad Institute in Boston, told Psychiatric News that these findings reinforce other recent research that has shown a lot of genetic overlap among psychiatric disorders.

“There is probably no single risk gene or genes shared across all psychiatric disorders, but the data are suggesting that there are clusters of disorders with similar genetic risk factors,” said Hyman, who wrote an editorial that accompanied this study.

“For the research community, these findings provide a strong take-home message,” Hyman continued. “We won’t understand the biology of mental illness if we only study these disorders in individual silos.”

To make these findings more widely accessible, McGrath and his team used data from the study to create interactive charts (available online at no charge at detailing age- and gender-specific risks of psychiatric comorbidity. For example, the risk charts show that a woman diagnosed with depression before age 20 has about a 40 percent chance to also be diagnosed with a neurotic disorder within five years, and a 50 percent chance to be diagnosed within 15 years.

“We hope that doctors will make use of these charts to help guide treatment discussions with their patients, and perhaps steps to reduce the risk of psychiatric comorbidity,” McGrath said. “There is always some potential danger for putting risk data out there; it may cause stress in some cases. But I think knowledge is better than ignorance, and if used properly, this information can help in disease prevention.”

This study was supported by the Danish National Research Foundation. ■