Childhood Mental Illness, Treatment Vary by State

Abstract

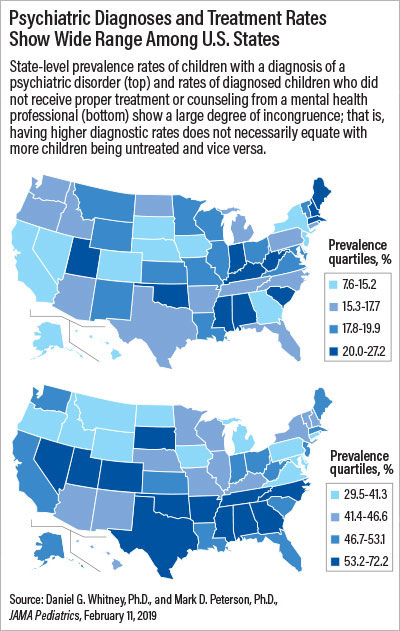

Overall, 16.5 percent of school-age children were diagnosed with at least one mental illness according to 2016 data, but state-level prevalence varied from about 8 percent to 27 percent.

A key element to successfully implementing broad mental health care initiatives for children is to understand where the greatest needs are and where resources are lacking. To that end, researchers at the University of Michigan have compiled state-level estimates of the prevalence of mental illness in children and their access to treatment for these disorders.

Daniel Whitney, Ph.D., and Mark Petersen, Ph.D., of Michigan’s Department of Physical Health and Rehabilitation found that about 16.5 percent of school-age children in the United States have at least one mental health disorder. About half of these children did not receive treatment in the past year. The study, published in the February 11 JAMA Pediatrics, also revealed variability in the estimates from state to state.

The researchers analyzed data from the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health. As part of the survey, which included information on over 50,000 children aged 0 to 17, parents were asked whether they had ever been told by a doctor or other health care provider that their child has a mental health disorder and, if yes, whether the child currently had the condition. The survey also asked parents whether the child had received any treatment or counseling from a mental health professional during the past 12 months. According to the survey, mental health professionals include psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, and clinical social workers.

The analysis by Whitney and Petersen excluded children without health insurance and younger than 6 years old.

Extrapolating to a national population of 46.6 million children in this age range, Whitney and Petersen estimated that 7.7 million children (16.5 percent) had at least one mental disorder in 2016. Children living with a single parent, children who had public insurance, children with special needs, and children who did not have a regular doctor or place of care were more likely to have a mental disorder. The prevalence ranged from a low of 7.6 percent in Hawaii to 27.2 percent in Maine.

The researchers estimated that 49.4 percent of the children with at least one mental disorder did not receive treatment or counseling from a mental health professional in the prior 12 months. Again, state-level rates varied from a low of 29.5 percent in the District of Columbia to 72.2 percent in North Carolina.

Whitney and Petersen then divided the states into quartiles based on prevalence or treatment rates. They found that states with higher prevalence of children with at least one mental health disorder did not necessarily have higher numbers of children not receiving needed treatment; of the 13 states in the top quartile of the prevalence of children with mental health disorders, four states—Alabama, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Utah—were also in the top quartile for children who were not receiving needed treatment. Colorado and Georgia, which had lower than average rates of children with mental health disorders, had a remarkably high prevalence of children not receiving needed treatment. In contrast, Virginia and Wyoming had higher than average rates of children with mental health disorders but lower than average rates of children not receiving needed treatment compared with other states.

Whitney told Psychiatric News that despite some differences between the states, he still believes national policies aimed at improving pediatric mental health care can be effective. “To maximize the impact of national level policies, there may be a need for some states to do some tweaking,” he said.

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research. ■

“U.S. National and State-Level Prevalence of Mental Health Disorders and Disparities of Mental Health Care Use in Children” can be accessed here.