Digital Archive Traces Admissions to Country’s First Mental Hospital for Blacks

Abstract

“Colored persons of unsound mind” were segregated in psychiatric hospitals in Virginia until segregation was outlawed. This article is part of a yearlong series marking APA’s 175th anniversary.

No provisions having been made here for the comfortable accommodation of this class of patients, we have never found it practicable to admit them, although occasional applications have been made to us on behalf of free blacks and frequently of slaves. We will simply remark that for many reasons it would be desirable that an institution for colored persons should be entirely distinct from those occupied by insane whites. —Francis Stribling, M.D. Annual Report of Western Lunatic Asylum, 1845

This photo appears in the 45th Annual Report of Central State Hospital (1915) in Petersburg, Va. The women are engaged in a “diversional occupation” class, whose teacher was said to be “very zealous and competent.”

The policy of separate asylums based on race was debated by Drs. John Galt and Francis Stribling, leaders of the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane, from 1844 to the publication of Galt’s final report in 1853. However, the policy became law in 1869 when Union Army General Edward S. Canby issued a legally “binding” order requiring the Virginia legislature to convert Howards Grove, a former Confederate hospital outside of Richmond, Va., to a state-run multipurpose health and welfare facility for destitute and homeless freedmen suffering from various illnesses. The legislature formally accepted Howards Grove as a temporary mental hospital on June 7, 1870, and built Central Lunatic Asylum for Colored Insane as a permanent statewide facility in Petersburg, Va., in 1885. It was renamed Central State Hospital in 1895. The hospital remained segregated by race until 1968, when federal law required integration.

The 100-year history of segregated admissions produced over 800,000 archival records that have been collected, copied, and analyzed. Preliminary analysis of these historical archival documents provides a demographic overview of people admitted, admission rates by decade, and diagnoses by race to 1940. Virginia law prevents access to records past 1940.

Historically, Central State Hospital used a standard admission registration card to collect identifying data in 15 categories for each person admitted. Data were gathered from patients, families, and commitment orders from the courts. Categorical data included basic demographic information: name, age, race, sex, place of residence, occupation, and marital status. Clinical information such as type of admission, date of admission, diagnosis, cause of illness, length of stay, condition at discharge, mortality, and cause of mortality were also collected. All data were maintained in two types of patient registration books (by name and by county/city) held in medical records and the hospital library.

The initial source of admissions and diagnoses varied. A relatively small number of psychiatric patients were transferred from Eastern Lunatic Asylum, local jails, and a private hospital in Richmond. In its first years, admissions of individuals with primary health care and economic needs greatly exceeded those with severe mental illness. Initially, patients admitted were of varying ages and conditions, with homelessness, developmental delays, and poverty contributing to the institution’s overall census, complexity, and treatment outcomes.

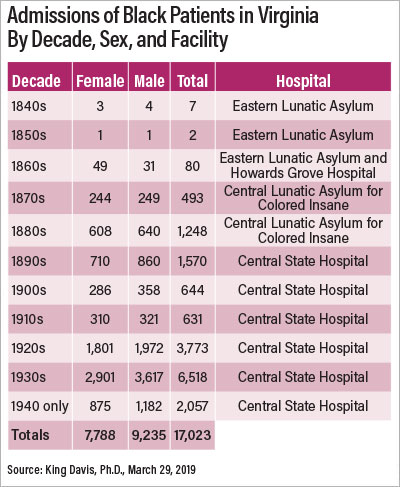

Gradually, the number of patients admitted with psychiatric symptoms increased. In part, the increase came about because Howards Grove, once under state control, could accept only psychiatric patients based on the “binding order” from General Canby in 1869. The rapid growth in excess admissions, greater than the black proportion of the population, started a pattern that would extend throughout the 19th and well into the 20th century. See the table on page 9 for data on admissions by decade, gender, and hospital. Eastern Lunatic Asylum admitted free blacks from 1840 to 1860 when John Galt was the medical director.

The 1920s and 1930s were the decades of the largest historical increases in overall admissions to Central State Hospital. These increases paralleled unprecedented increases in admitting diagnoses of psychosis, dementia, and developmental delay. Although admission numbers are available only for 1940, the one-year total of 2,057 suggests that the 1940s will be the largest in the facility’s history, greatly exceeding its capacity.

Many of these earlier increases in admissions occurred during the post-emancipation years as the black population in Virginia sought to adjust to an uncertain place in the post-slavery economy. It seems likely that the increases in the 1920s and 1930s were also related to changes and unpredictability for blacks in an economy crippled by depression.

Slightly over 80 percent of all admissions were of individuals aged 18 to 54, 13 percent were aged 55 and over, and less than 5 percent were under age 18. These differences were statistically significant and became more pronounced from the 1890s to the 1930s.

Project Is Preserving Important Chapter of American History

The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation provided generous support to researchers from the School of Information at the University of Texas at Austin to collect, catalog, restore, and analyze documents from Eastern Lunatic Asylum, Howards Grove Hospital, and Central Lunatic Asylum for Colored Insane (renamed Central State Hospital in 1895) from 1840 to 1940. The project started in 2008 with financial support from the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors and the president of the University of Texas at Austin to make digital copies of 800,000 documents. Initially, the goal of the project was to preserve these historical documents that had been maintained in nonarchival environments subject to extremes in temperature, humidity, sunlight, and frequent usage.

The goal for the project expanded to identify methods to increase access to these documents by family members and scholars if it could be demonstrated that there was not a loss of privacy or violation of ethics. Permission to make digital copies of all documents and photographs was obtained from the Virginia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services, the Library of Virginia, and from the Director of Central State Hospital.

Geographically, most admissions came from cities and counties that were near the hospital and had large black populations. The largest number of admissions came from the cities of Richmond, Petersburg, and Norfolk and the counties of Charlotte, Pittsylvania, Henry, Patrick, and Carroll. Fewer than 20 people were admitted from Kentucky and Washington, D.C. Almost all the people admitted through 1940 were identified as laborers, with some in semi-skilled to skilled positions as carpenters, plumbers, and shoemakers. Of the 17,023 persons admitted from 1870 to 1940, fewer than 50 held professional positions as teachers, preachers, or lawyers.

Data from the hospital’s admission registers showed that 220 diagnostic labels were used to describe patients’ mental illnesses from 1840 to 1940. For statistical analysis, we collapsed the 220 diagnoses into nine categories consistent with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The range and types of diagnoses over this 100-year period reflect the multipurpose functions of Central State Hospital and other state hospitals. The most frequent diagnosis that qualified a person for admission was psychosis (66 percent) as manifested most often in mania. Dementia was the second most frequent diagnosis (10 percent), and personality disorders and anxiety the least frequent.

There were some diagnostic differences by gender. The most frequent diagnosis given was psychosis, and a slightly higher percentage of women were diagnosed with psychosis than men. The percentage of men diagnosed with alcoholism was close to five times greater than for women, while the percentage of women with affective disorders was almost twice that of men. A higher percentage of women were diagnosed with developmental disorders and physical disease than men, while a higher percentage of men were diagnosed with epilepsy.

King Davis, Ph.D., is a senior research fellow in the School of Information at the University of Texas at Austin. He is also the former commissioner of behavioral health and developmental services for the Commonwealth of Virginia.

The most unexpected finding in the diagnostic data was the significant increases in three disorders from 1920 to 1939: dementia, psychosis, and developmental disorders. Forty-five percent of all admissions for psychosis occurred from the 1920s through 1939. In 1910, there were only 527 admissions for psychosis, but in 1920 the number rose to 2,459 and in the 1930s to 3,957. Diagnoses of dementia increased from 30 in the 1910s to 443 in the 1920s and to 619 in the 1930s. Admission diagnoses of developmental disorders increased from 20 in the 1910 decade to 335 in the 1920s and to 733 in the 1930s.

Although only data up to 1940 are legally available, the one-year total appears to continue the significant patterns seen in the 1920s and 1930s. In the second phase of this project, we will use a variety of statistical measures to identify and weigh factors that help explain the findings. ■