Guns of War Dampened Centennial Celebration

Abstract

Many veterans returned injured from the war—psychologically if not physically—and it sparked a period of increased funding for mental health and psychiatry departments at U.S. medical schools.

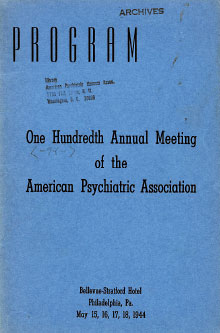

The time was May 1944, less than a month before D-Day, and many of the 2,297 psychiatrists attending APA’s Annual Meeting marking the Association’s centennial anniversary at the Hotel Bellevue Stratford in Philadelphia were in uniform.

“The American Psychiatric Association has gone to war,” said APA President Edward A. Strecker, M.D., in his presidential address at the meeting 75 years ago, “on land and sea; in the air and beneath the surface of the oceans; in sodden Jungles, on burning desert sands, and in arctic wastes; on the home front, in hospitals, clinics, and medical schools. … Practically every member not barred by age, disability, or earmarked as essential for civilian psychiatry is on active duty. In all branches of war service, the psychiatric policy and direction is overwhelmingly in the hands of members of this Association.”

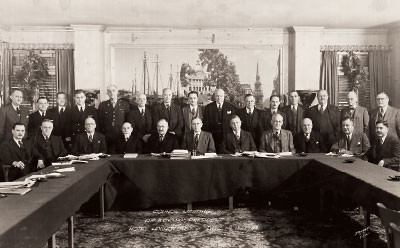

The APA Board of Trustees (then known as the “Council”) met at the Hotel Lexington in New York in December 1944. World War II ended in September 1945.

More has changed about psychiatry and APA than has stayed the same in the 75 years between its centennial celebration in Philadelphia and this year’s 175th anniversary. But then, as today, psychiatrists served their country and were urged to be politically active.

Walter Barton, M.D., a past president of APA and medical director of the Association from 1963 to 1974, was at the centennial celebration. In an interview held at the time of APA’s sesquicentennial in 1994, Barton recalled Strecker’s theme of the role of psychiatry in the preservation of democracy and the call for political activism.

“That’s relevant today, because unless psychiatrists are politically active, there won’t be adequate mental health benefits” for all those who need them, Barton said.

Centennial Celebration

In keeping with the twin theme of psychiatry’s heritage and the preservation of democracy, participants at the centennial meeting received copies of the Declaration of Independence and attended a dramatic presentation of the life of Benjamin Rush, considered to be the father of American psychiatry.

A history of the Association up to that point, 100 Years of American Psychiatry, was produced for the meeting by APA and the American Historical Association. At the time, Barton was heading a section on occupational therapy in the Surgeon General’s office, and like many of his colleagues, he arrived in Philadelphia in uniform. While details of the coming allied invasion in Normandy were unknown, of course, it was widely believed that something momentous was in the making, he said. Barton and Henry Brosin, M.D., also a past president who was in Philadelphia for the centennial and was interviewed in 1994, both remembered the annual meeting then as somewhat cozier than today.

“It was very much smaller than now,” Barton said. “Everyone knew everyone else.”

The entire meeting was run by one man—Austin Davies, Ph.D., executive assistant to the medical director—“with a sheaf of papers in his pocket,” Barton said. Total membership at the time was 3,125, compared with 38,500 today. The Association was governed by 12 “Councillors” who served for staggered terms of three years. The president-elect was Karl M. Bowman, M.D., who served for two terms. (The Annual Meeting in 1945 was canceled due to a railroad strike.)

Diverse Program

A glance at the program calendar for the 1944 meeting gives an indication of the extent to which the war in the Pacific and the impending introduction of American forces in the European theater dominated the atmosphere. There were sessions on “Psychiatric Aspects of Amphibious Warfare,” “Psychiatric Problems in Naval Personnel,” “Rehabilitation of Discharged Soldiers,” “Group Psychotherapy in War Neuroses,” “War Neuroses and Their Treatment in the African-Italian Theater of Operations,” and “Treatment of Combat Induced Emotional Disorder in a General Hospital.”

Nonetheless, the topics covered at the meeting were nearly as diverse as they are today, with sessions on neurology, psychotherapy, psychoanalysis, electroconvulsive therapy, psychosomatic medicine, research, and administrative psychiatry.

Some of the reports from committees at the meeting take on a special poignancy 75 years later.

“The time will come when the study of prevention will occupy our thoughts more constructively,” wrote John Whitehorn, M.D., and Karl Menninger, M.D., in their report from the Committee on Psychoanalysis. “As the field of child psychiatry is more earnestly cultivated in a spirit of research, the prophylactic implication of accumulated psychoanalytic knowledge will receive more recognition in the curricula of medical education and in the program of teacher education.”

Frederick H. Allen, M.D., Oskar Diethelm, M.D., and Harry Stack Sullivan, M.D., wrote this in their report from the Committee on Psychotherapy: “It is clear that psychotherapy, if it is to meet the needs obvious in our immediate future, must make rapid strides towards far better utilization of each physician’s patient-hours. The possible use of therapy aides—physical, chemical, and personal—also demands exploration. This is scarcely to be taken to encourage blind interference, either with human physiology or with social organization, in lieu of psychotherapy. Psychotherapy is at best an intensely responsible, most gravely careful, intervention in favor of the patient’s approximation to a more adequate general future of humanity.”

Turning Point

Brosin, who was a lieutenant colonel in the Army in 1944 and later promoted to full colonel, called the war a great turning point for APA and American psychiatry. Many veterans returned to the United States injured from the war—psychologically if not physically, he said—and it began a period of increasing funding for mental health and for psychiatry departments at medical schools all over the country.

“By the end of the war, the country was willing to vote money for psychiatric care,” Brosin said. “Overnight, it seemed, we got departments of psychiatry at all medical schools, which were funded between 1945 and 1950.” ■