Efforts to Describe Mental Illnesses Continue to Make Progress

Abstract

The long and challenging labor to bring psychiatric diagnostic standards into the modern world has improved patient care and made research more reliable and valid.

For Hippocrates and Galen and their followers over succeeding centuries, the four humors explained the origins of human personality and behavior. By the mid-19th century, however, scientists sought anatomical clues for mental illness. That model had a promising start. The discovery that syphilis caused general paresis of the insane and Alois Alzheimer’s recognition of neurofibrillary tangles in the brains of demented patients were valuable discoveries. But those observations were harder to extend to other disorders.

In Germany, Emil Kraepelin, in serial revisions of his textbook on psychiatry through the 1890s, abandoned any attempt at classification based on the anatomic characteristics of a given condition. Instead, he took meticulous notes on each patient and collated the accumulating evidence. He ultimately divided mental illnesses into the psychoses (dementia praecox, now termed schizophrenia) and the mood disorders (manic depressive [now bipolar] disorder).

In 1917, the Committee on Statistics for the American Psychiatric Association (then called the American Medico-Psychological Association), together with the National Committee on Mental Hygiene, formulated a plan for gathering uniform statistics across mental hospitals. This initiative resulted in the creation of the Statistical Manual for the Use of Institutions for the Insane, a first in the United States.

The next major step came after World War II. The war’s psychiatric aftereffects on military personnel pushed the Veterans Administration to develop criteria to manage patients in its care. At the same time, the World Health Organization (WHO) set about revising the International Lists of Causes of Death to include causes of morbidity, culminating in the publication of ICD-6 in 1948, the first version of the ICD to include diseases.

In 1948 APA began work on a variant of ICD-6, which was published in 1952 as the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The “Diagnostic” element was descriptive, and the “Statistical” was a nod to the psychiatrists running America’s mental asylums, said Darrel Regier, M.D., M.P.H., who served as vice chair of the DSM-5 Task Force and is a former director of APA’s Division of Research. He is now a senior scientist and adjunct professor in psychiatry at the Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences.

The first DSM was heavily influenced by the dominant psychoanalytic paradigm of the day, as was its successor, DSM-II, in 1968. Freudian terms like “neurosis” and “reaction” remained, as well as an emphasis on the social and intrapsychic causes of mental illness.

The definitions in both DSM-I and DSM-II were brief and not well differentiated, said DSM expert Michael First, M.D. For instance, one well-known study found that the same set of patient descriptions presented to psychiatrists in the United States and Great Britain resulted in radically different sets of diagnoses. First is a professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University and a research psychiatrist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. He was heavily involved in editing the text and criteria in DSM-IV and DSM-IV-TR and was an editorial consultant on DSM-5 and is now a member of the DSM Steering Committee and co-chair and editor of the DSM-5 text revision (DSM-5-TR).

Loose definitions of mental illness were not just a clinical problem. Researchers lacked consistent standards by which to recruit subjects and measure treatment effects. Insurance companies were increasingly cautious about paying for making a diagnosis and care they saw as ill defined.

In the 1950s, WHO sponsored a comprehensive review of diagnostic issues, conducted by the British psychiatrist Erwin Stengel, M.D. He called for explicit definitions of disorders as a means of promoting reliable clinical diagnoses.

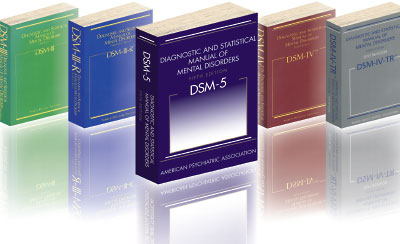

As the knowledge about psychiatric illnesses has progressed, APA’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders has been updated regularly since the first edition was published in 1952. Here are the publication dates of later editions: DSM-II: 1968; DSM-III: 1980; DSM-III-R: 1987; DSM-IV: 1994; DSM-IV-TR: 2000; and DSM-5: 2013. DSM-5-TR is now in development.

“DSM-I and DSM-II had little impact on the mental health fields,” said First. “They were mainly used for statistical purposes, especially in state systems, which needed a system for routine reporting on their patient populations. The move to DSM-III in the early 1970s was motivated by a desire to tackle perceived problems with both the reliability and validity of psychiatric disorders. Both researchers and clinicians needed better definitions.”

APA selected Robert Spitzer, M.D., to head up the development of DSM-III. He had worked on DSM-II and was instrumental in having homosexuality removed as a mental disorder from DSM-III. (An article that focuses on the removal of homosexuality from DSM will appear in the next issue.)

Spitzer wanted psychiatric diagnoses to be defined in terms of purely descriptive symptoms, without the implied etiology suggested by psychoanalytic language, said First.

Much of the groundwork for that had been laid by Eli Robins, M.D., and a group of other psychiatrists at Washington University in St. Louis, who focused on the biology of the brain, said Regier.

In 1972 John Feighner, M.D., of Washington University in St. Louis and colleagues published “Diagnostic Criteria for Use in Psychiatric Research” in the January 1972 Archives of General Psychiatry. The Feighner Criteria helped standardize the definitions of 16 disorders for use by researchers in recruiting subjects for research studies.

“The team that developed the Feighner Criteria made three key contributions to psychiatry: the systematic use of operationalized diagnostic criteria; the reintroduction of an emphasis on illness course and outcome; and an emphasis on the need, whenever possible, to base diagnostic criteria on empirical evidence,” wrote Kenneth Kendler, M.D., Rodrigo Muñoz, M.D., and George Murphy, M.D., in “The Development of the Feighner Criteria: A Historical Perspective” in the February 2010 American Journal of Psychiatry.

Robert Spitzer, M.D., is recognized for pioneering a system of measurement and assessment for diagnosing mental illnesses that helped move American psychiatry toward a more evidence-based nosology.

Spitzer refined and expanded them into the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) for an NIMH study on the psychobiology of depression, and they became the precursors to DSM-III. However, in developing diagnostic criteria for DSM-III, Spitzer went beyond both the Feighner and RDC criteria. His team put them into a consistent format and then used a system whereby a certain number of symptoms were required to make a diagnosis. The result, published in 1980, was groundbreaking.

“DSM-III took over the world of mental health practice—it’s descriptive atheoretical approach and its precise definitions allowed it to be embraced by researchers and clinician across the mental health professions,” said First.

Inevitably, such a major shift in approach would be imperfect. DSM-III was revised (as DSM-III-R) in 1987, the focus of which was correcting errors as well as reflecting the results of research that was sparked by the availability of the DSM-III diagnostic criteria. The next major revision came with DSM-IV in 1994. Its main innovation was the establishment of a three-stage empirical review process that involved literature reviews, MacArthur Foundation-funded reanalyses of existing datasets, and the conducting of disorder-specific field trials to test diagnostic proposals. Moreover, there was a concerted effort to harmonize with ICD-10, which was also in development at the same time and came out in 1992. In recognition of the fact that too-frequent changes to the diagnostic criteria sets are disruptive to both clinicians and researchers but also recognizing the important of keeping the information in the DSM text up to date, a text revision, DSM-IV-TR, came out in 2000.

Work on DSM-5 began in 2000, when APA convened work groups to design the research agenda for the manual. That effort resulted in numerous monographs and articles, as well as one book, A Research Agenda for DSM-5. APA formed the DSM-5 Task Force under the direction of David Kupfer, M.D., to commence the revision process in earnest.

The lack of discrete boundaries between disorders and between disorders and normality suggested the need for a dimensional approach, an idea developed into the spectrum model. New genetic research was revealing that hundreds, perhaps thousands of genes with small effects underlie most cases of disorders like autism and schizophrenia. Combined with environmental exposures, this led to disease presentations that varied in severity and course. The Task Force on DSM-5 adopted a new approach, identifying central tendencies of diagnostic categories but not narrowly limiting them, said Regier. DSM-5 entries not only included a diagnostic classification and diagnostic criteria sets but also extended discussions of prevalence, diagnostic features, course of illness, cultural and gender issues, and other matters.

Drafts were posted online to promote transparency and stimulate feedback during the process. Another innovation with DSM-5 was the establishment upon publication of a “continuous improvement model” for the revision process. “APA invites proposals for changes to DSM-5,” says the manual’s website. “Changes will be made on a rolling basis, as warranted by advances in the science of mental disorders.”

The process of reviewing proposed revisions is overseen by the DSM Steering Committee, chaired by past APA President Paul Appelbaum, M.D. (Psychiatric News) “It will be interesting to see how the DSM evolves now that we’re seeing more dimensional approaches and advances in the biology of mental illness,” said Regier. ■