Arkansas Community Showcases Disparities Facing Pacific Islanders in United States

Abstract

Beset by physical and mental health problems, the Marshallese in and around Springdale, Ark., have been ravaged by COVID-19.

In America’s heartland, at the convergence of the Midwest and South, lies an unexpected ethnic community. Far from their homeland, about 15,000 natives of the Marshall Islands—an archipelago of 29 coral atolls in the Western Pacific—have settled in the northwest Arkansas town of Springdale and the surrounding regions. Though not a huge population, the Arkansas Marshallese are one of the fastest growing Pacific Islander communities in the United States, according to census data.

As evidenced by the fresh plots in a local graveyard, COVID-19 has taken a significant toll on a small Marshallese community in Arkansas, which is impacting the psychological health of the population.

They are also one of the communities hardest hit by COVID-19; recent data indicate that the Marshallese—who make up less than 0.4% of Arkansas’ population—accounted for nearly 5% of all COVID-19 deaths in the state as of September.

“It’s possible that everyone in this community will personally know someone who died of COVID, and that sort of mass trauma leaves a mark,” said Andrew Subica, Ph.D., an assistant professor of social medicine and population health at the University of California, Riverside. “The legacy of this pandemic on the Marshallese community will be long lasting and is expected to have ill effects for their psychological well-being.”

As one of the few mainland researchers addressing mental illness and substance use among Pacific Islanders, Subica knows the news of the Arkansas Marshallese or other Pacific Islander pockets in places like Los Angeles or Utah may not draw widespread attention. But the Marshallese pandemic is a prime example of how health disparities can ravage an overlooked population.

History of Health Issues

The Marshallese first came to the United States en masse in the mid-1980s after the two countries finalized a Compact of Free Association, which permitted Marshallese to freely travel to and work in the United States. Many were drawn to northwest Arkansas, which had a booming meat and poultry industry.

The Marshallese brought an island culture to America’s heartland, but they also brought their health issues, including obesity and diabetes.

Members of the Arkansas Coalition of Marshallese help gather food and clothing to support their Pacific Islander community.

The problems can be traced back to 1946, when the United States began using this island chain to conduct dozens of nuclear tests over the next 12 years. In addition to displacing many residents from their home islands, the fallout from the tests contaminated the nearby land and sea, forcing the Marshallese to rely on canned and processed food. A recent analysis of the health of the Arkansas Marshallese adults found that about 38% had diabetes, 41% had hypertension, and 62% were obese. Among the general population, the rates for these three conditions are about 9%, 29%, and 35%, respectively.

Pearl McElfish, Ph.D., co-director of the Center for Pacific Islander Health at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) Northwest Regional Campus, first learned about the history of the Arkansas Marshallese when she was the director of community health and research at UAMS. After receiving multiple grants to address health disparities in the Springdale region, McElfish saw an opportunity for a research and training center focused on Pacific Islander health. The UAMS Center for Pacific Islander Health was created in 2015.

“A research center like that had never been established in the U.S.,” explained McElfish, who is also the vice chancellor at UAMS. There were other centers that studied Pacific Islanders, but they were always grouped alongside Asian Americans, she explained. “Based on their history of displacement as well as their cultural traditions, the Marshallese are more akin to Native Americans than Asian Americans,” said McElfish. “They deserve their own focus.”

Subica, who has conducted mental health surveys among the Marshallese as part of his research, concurs. As an example, he noted that Asian Americans tend to have low rates of alcohol or substance use problems, whereas Pacific Islanders, especially young adults, have tremendous problems with drinking and substance use. A recent survey he conducted suggested the prevalence of alcohol use disorder among Marshallese was nearly four times the national average of 5.8%. His surveys also identified rates of major depression and anxiety disorder to be 21% and 12%, respectively, in this population.

But since Pacific Islanders are less populous than Asians Americans, these data can get hidden in a large sampling of both groups. “If we want to improve the health of these communities, we absolutely have to disaggregate Pacific Islanders from Asian Americans,” he said.

Community Organizations Provide Center’s Boots on Ground

Since opening in 2015, the Center for Pacific Islander Health has focused on two major health issues: the treatment and prevention of diabetes and improved maternal health.

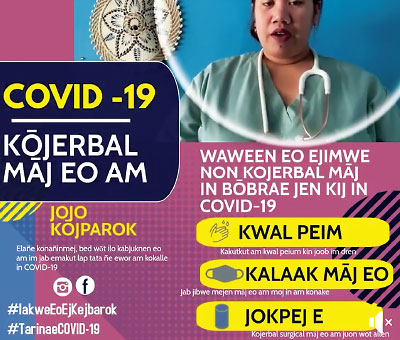

The Arkansas Coalition of Marshallese hosts a weekly Facebook session with a nurse to keep the community safe and informed about COVID-19.

“We found in our surveys that 25% of Marshallese women had no prenatal care prior to delivery, while about half of the rest do not receive care until their second trimester,” McElfish said. This lack of care was troubling, McElfish noted, given that elevated rates of diabetes or alcohol use disorder can increase the prevalence of pre-term and/or low-weight births.

McElfish told Psychiatric News that they are currently working to expand the breadth of health issues that are the focus of the center. “We know we have barely scratched the surface of the numerous health disparities facing the Marshallese, but this is a group that has been overlooked in health care and we have learned each area of study will require a significant commitment,” she said. To ensure the development of screening tools or behavioral interventions that are culturally sensitive and factor in traits such as the strong family tradition of Pacific Islanders and the value they place in church, the Center for Pacific Islander Health collaborates with local advocacy groups such as the Marshallese Education Initiative and the Arkansas Coalition of Marshallese (ACOM). ACOM is dedicated to empowering the Marshallese community through education, health, skills training, and cultural awareness. “This was a central strategy from the start; these organizations are the bridge to connect the Marshallese people with health care in a positive way,” McElfish said.

“Teaming up with local groups is essential to conducting good, ethical community-based research with Pacific Islanders,” said Subica, who has conducted community studies with the Arkansas Marshallese as well as other Pacific Islander groups throughout the United States and understands the challenges with engaging this population in research. “I would not have been able to do any surveys in Arkansas without the support and effort of ACOM.”

“Normally, when we want to design a more culturally relevant behavioral therapy for Latinx or African-American individuals, we would recruit people through community clinics and work with them to tailor our interventions,” he continued. “But when I went to various Pacific Islander communities, they politely let me know I could create all the culturally focused therapies I wanted for them, but that won’t get them to walk in the door when it comes to their mental health.”

Subica explained that some of that recalcitrance is due to common treatment barriers such as stigma or uncertainty about what constitutes a psychiatric disorder. But through his partnership with Pacific Islander communities, Subica also found that they have great uncertainty about the treatment process. Rather than questions such as what cognitive-behavioral therapy entails, many Pacific Islanders possess concerns about the confidentiality and cost of therapy. “An important step would therefore be to demystify the treatment process,” he said. As part of his community work, Subica is filming small narrative segments of Pacific Islanders discussing mental health with their pastor and learning about different treatments.

McElfish noted that the Center for Pacific Islander Health was beginning to explore mental health in the Marshallese by looking at better ways to screen patients for depression at their clinic. And then came COVID-19.

COVID-19’s Psychological Toll

“By nature, we are a resilient community, but COVID has hit us very hard,” said Melisa Laelan, founder and director of ACOM. “And the biggest question asked of us is why.”

The pieces for the perfect storm were all in place. The Marshallese are heavily represented in the beef and poultry plants that are ripe for a large-scale virus outbreak, they typically live in multigenerational households that allow further virus spread, they are more likely to have the twin risk factors of diabetes and obesity that lead to worse COVID-19 outcomes, and they have less access to quality health care.

“Based on history, we can also assume that COVID-19 is going to lead to increased depression, anxiety, and addiction down the road,” Subica said. His concern is that, as a group, Pacific Islanders already have elevated rates of these issues coupled with a reduced desire to seek treatments. Problems like interpersonal violence or suicide might reach their own pandemic proportions, he said.

Since the overall population of Pacific Islanders in the states is still small—and since they are often grouped with Asian Americans in census data as well as government health statistics—the toll of COVID-19 on this group has been overlooked nationally. “Even our state government doesn’t have a sense of urgency when it comes to our community,” noted Laelan, who has been fiercely advocating for Marshallese not to be forgotten when states distribute resources from the various federal stimulus packages passed over the past few months.

As they await much needed assistance, Laelan and ACOM have been doing what they can to support the Marshallese, and their proactive efforts at addressing health disparities over the past decade may have kept a bad situation from becoming worse.

ACOM was a loosely organized coalition when Laelan founded it in 2011, but the organization received a big boost in 2015 when McElfish approached her and asked her group to help implement a $3 million grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention aimed at improving health disparities in northwest Arkansas’ Hispanic and Marshallese communities.

As her own mother had recently been diagnosed with diabetes, Laelan understood all too well the health issues plaguing her community. “We knew that we had to address the structural factors contributing to poor health to make an impact,” she said. The partnership with UAMS offered that opportunity.

Over the next years, ACOM initiated programs such as delivering healthy food to households to reduce the reliance on canned goods; advocating for health insurance reform (though the Marshallese have a quasi-legal status through the free compact, they are not U.S. citizens and therefore not eligible for Medicaid, thus leaving many uninsured); and establishing a resource center to help people with social, financial, or substance use problems.

During the COVID-19 crisis, the organization has ramped up food delivery services to help households that need to isolate and is busy translating important public health information into Marshallese. Through their Facebook page, ACOM also hosts a weekly show with a Marshallese nurse that offers tips on how to stay safe, whether at the factory or when arranging a burial service for a loved one.

“It may be too late to protect those who already got sick, but we might be able to make the lives of their families easier and prevent COVID from causing more crises,” Laelan said. ■

“Diabetes and Hypertension in Marshallese Adults: Results from Faith-Based Health Screenings” is posted here.

“Mental Health Status, Need, and Unmet Need for Mental Health Services Among U.S. Pacific Islanders” is posted here.

More information on the Center for Pacific Islander Health is available here.

More information on the Arkansas Coalition of Marshallese is available here.