Tardive Dyskinesia Treatments Offer Welcome Relief to Patients

Abstract

As antipsychotic use has grown over recent decades, so too has the number of people experiencing the irregular and involuntary muscle spasms associated with these medications.

Since their discovery in the 1950s, antipsychotics have remained the best option for treating psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses. And for nearly as long, there has been evidence that they can induce a debilitating and possibly irreversible neurological side effect known as tardive dyskinesia (TD).

Despite this association, antipsychotic use has steadily grown in psychiatry over the decades in patients of all ages. As a result, millions of patients are at risk of experiencing the irregular and involuntary movements of TD.

The recent FDA approval of two drugs that can effectively treat TD—valbenazine and deutetrabenazine—has been a game changer for patients experiencing this side effect.

Experts Debate Origin of TD

The first cases of TD among patients with schizophrenia taking first-generation antipsychotics were documented in Germany in 1957. Over the next decade, as more case reports surfaced in Europe and the United States, there was extensive debate over the nature of these movement problems, noted Henry Nasrallah, M.D., a professor of psychiatry, neurology, and neuroscience, and director of the schizophrenia program at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. Some physicians thought these movements—which typically manifest as tongue flicks, lip smacks, or facial grimacing—were inherent motor symptoms of schizophrenia, but others attributed the symptoms to the medications being prescribed to these patients.

“In the early years, physicians hammered their patients with large antipsychotic doses, which caused acute extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) such as severe muscle spasms (dystonia) within a few hours, and rigidity and tremors within two to four weeks,” Nasrallah said. “It became evident that the patients who received the highest doses and had the most severe EPS were more likely to develop TD later on.”

By the late 1960s a consensus emerged that TD was a side effect of long-term antipsychotic use and researchers began looking for treatments. But despite numerous attempts at treating TD, no effective therapies could be found.

The emergence of second-generation antipsychotics in the mid-1990s brought some relief to patients as these medications had a lower risk of TD than first-generation antipsychotics. Data from different studies indicate that about 5% of adults taking a first-generation antipsychotic develop TD after each year of use; for second-generation drugs, these rates are about 1% to 2% per year, Nasrallah said.

“But less risk does not equal zero risk,” cautioned Stanley Caroff, M.D., an emeritus professor of psychiatry at the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center and the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine. “And these new antipsychotic medications are being marketed and prescribed to more people with a variety of illnesses.”

TD Can Have Negative Psychological Impact on Patients

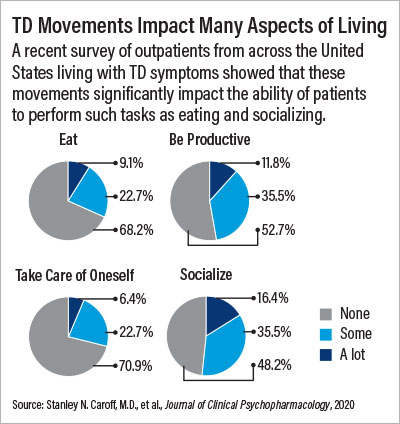

A pair of recent studies Caroff has been involved with have also revealed the potential impact that TD has on patients. RE-KINECT, a study supported by valbenazine manufacturer Neurocrine Biosciences, assessed over 700 patients taking antipsychotics for at least three months from outpatient sites across the United States. Twenty-seven percent of the participants screened positive for possible TD, and among this group three-quarters affirmed that TD made them feel self-conscious or embarrassed. Over 40% also said their TD negatively impacted their ability to do their usual activities or socialize.

The second analysis from Teva Pharmaceuticals—which manufactures deutetrabenazine—highlights how external observers may stigmatize people displaying symptoms of TD. In this randomized study, participants watched actors in various social interactions, such as a first date or a job interview. In some scenarios, actors simulated TD movements; in control scenarios they did not. The participants were then asked to rate their attitudes toward the actors (for example, how likely they would be to date the actor). The participants consistently rated their reactions to actors with TD significantly lower.

“This is more significant than feeling embarrassed,” Caroff said. “Imagine you are someone with schizophrenia on the road to recovery and going to your first job interview. To think it might be derailed by some involuntary movements caused by your medication is concerning.”

Available Treatments

The discovery that TD was associated with a nerve receptor known as VMAT2 and the subsequent development of VMAT2-inhibiting drugs now means patients experiencing symptoms of TD have multiple options for relief, explained Joseph McEvoy, M.D., the Case Distinguished Chair in Psychotic Disorders at the Medical College of Georgia in Augusta.

“Both of these drugs [valbenazine and deutetrabenazine] really work, and work rapidly,” he said. “An objective observer could notice a difference in movements within one week, and by one year of use, involuntary movements are often virtually undetectable.”

“VMAT2 inhibitors have truly been a positive development for patient care and psychiatry.” Caroff added. “Besides the therapeutic benefit, these medications have been instrumental in reviving psychiatrists’ interests in TD.”

But VMAT2 inhibitors, while effective, can create challenges for some patients, including drowsiness or parkinsonism, Caroff continued. Additionally, “while these medications suppress TD, which can be life-changing for many patients, they do not cure it,” he said. Long-term studies with VMAT2 inhibitors have shown that once patients stop taking either drug, their TD often returns to baseline levels. Finally, there are the logistical burdens; many patients with a serious mental illness such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder taking antipsychotics already take multiple medications, and VMAT2 inhibitors are one more set of pills they have to pay for and remember to take each day.

How to Recognize TD

Before prescribing VMAT2 inhibitors to patients, physicians must first differentiate TD movements from other shakes, spasms, and tremors that can arise from antipsychotic use like acute dystonia, Nasrallah said.

Unlike irregular TD movements, other antipsychotic-associated movements are more rhythmic, rarely involve facial muscles, and tend to occur within the first few hours, days, or weeks of treatment. With the exception of geriatric patients, in whom TD can emerge within a few months of antipsychotic treatment, Nasrallah noted that “TD usually starts slowly and evolves over time, so it may not be recognized and diagnosed in the early stage of treatment.”

About 25% of patients with schizophrenia have repetitive facial or body mannerisms known as stereotypies that can also complicate a TD diagnosis. Psychiatrists, however, can identify TD with a 12-point examination known as the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS), in which patients are asked to perform such procedures as opening their mouth and sticking out their tongue while tapping their thumbs. The AIMS evaluation only takes a few minutes to complete, according to Nasrallah.

Caroff cautioned that an AIMS focuses on how prominent and severe the actual movements are, so physicians should also take time to ask more detailed questions about the impact of TD on patients’ lives. Even mild TD may impair quality of life and functioning. There are currently no proven clinical scales to measure the social or personal impact of a movement disorder.

Let the patient guide you, McEvoy suggested. “Ask them what symptoms bother them the most, or better yet, ask them if their work or social life has changed since starting their antipsychotic. Importantly, convey a message of hope if they talk about abnormal movements, because now we can fix it.”

McEvoy was an investigator on Teva’s deutetrabenazine clinical trial AIM-TD and served on its advisory board. Nasrallah and Caroff have provided consultation for both Neurocrine and Teva. Caroff has also received a research grant from Neurocrine. ■