Polysubstance Use Common in SUD Patients

Abstract

Some patients who stop using their preferred substance increase their use of other substances.

More than half of patients who are hospitalized and have a substance use disorder (SUD) use more than one substance, a study in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment suggests. The study, which looked at substance use patterns among patients admitted to general hospitals for acute illness, also found that nearly 70% of patients who used opioids had also used substances such as alcohol, cocaine, or amphetamines at some point in the month before hospitalization.

Hospital-based interventions for substance abuse must take a broad approach, says Honora Englander, M.D.

The findings demonstrate the need for hospital-based interventions, which often focus on just one substance, to take a broader approach, senior author Honora Englander, M.D., told Psychiatric News. Englander is an associate professor of medicine in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) School of Medicine.

“Our study underscores that in hospitalized adults, polysubstance use is the norm, not the exception. This is important as we think about treatment systems, harm reduction efforts, and policy,” Englander said. “The recent national focus on the ‘opioid epidemic,’ while important, may miss the mark and oversimplify patterns of substance use for many people.”

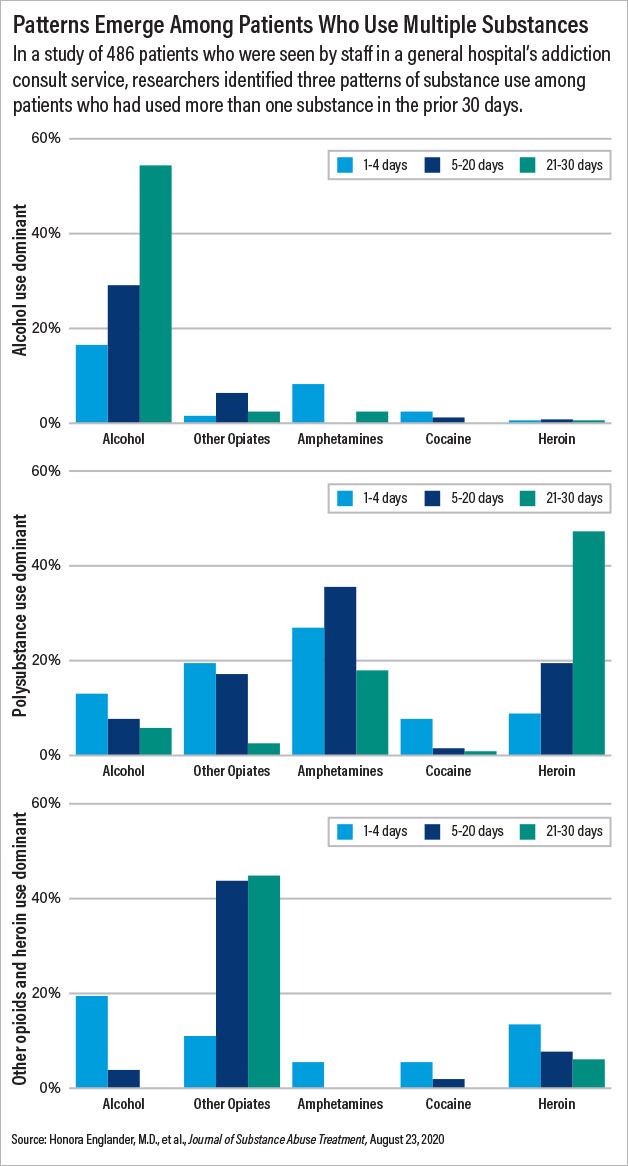

Englander and her colleagues analyzed data from 486 patients who were seen by staff in an addiction medicine consult service at OHSU Hospital between 2015 and 2018. Roughly 36% of the patients were homeless. The researchers used the Addiction Severity Index-Lite to survey patients about their history of substance use, and then followed up once with patients between 30 and 90 days after the patients were discharged. At follow-up, the researchers asked the patients about their use of heroin, other opioids, alcohol, amphetamines, and cocaine. If patients were hospitalized again within 30 to 90 days of their discharge, the researchers interviewed them at the hospital. The researchers found that nearly 53% of patients with SUD used at least two substances.

In the analysis, the researchers also identified subgroups of patients who used one or more substances. At baseline, three patterns emerged: alcohol use dominant, polysubstance use dominant, and heroin/other opioid use dominant. Among those in the polysubstance use dominant group, about 35% used amphetamines five to 20 days a month, 18% used amphetamines more than 21 days a month, nearly 20% used heroin five to 20 days a month, and nearly 48% used heroin more than 21 days a month.

At follow-up, just over 40% of patients reported abstaining from at least one substance they had been using before they were hospitalized. Roughly 28% of those who reported any alcohol use at baseline transitioned to no days of use at follow-up. Among those who reported heroin use at baseline, 19% reported no days of use at follow-up. Of those who reported non-heroin opioid use at baseline, roughly 21% reported no further use of non-heroin opioids at follow-up.

Some patients who reported limiting or abstaining from their preferred substance at follow-up increased their use of other substances. For example, alcohol consumption increased in some patients who decreased or stopped using heroin or other opioids. Others who primarily used heroin and methamphetamine at baseline reported using non-heroin opioids after discharge.

“This was surprising, and we still aren’t sure why it happened,” said lead author Caroline King, M.P.H., who is a medical and doctoral student at the OHSU School of Medicine. “It could be that patients were prescribed other opioids and included those in their [follow-up] survey response or it could be that they transitioned to using other substances after discharge.”

Overall, the results add to a growing body of literature about the usefulness of interprofessional, hospital-based addiction medicine consult services, Englander said. “Hospitalization is a reachable moment to initiate addictions care, start lifesaving medication for opioid use disorder, increase patient trust in hospital providers, and increase engagement in addictions care after discharge.”

Some patients who stop using heroin may transition to other substances, including non-heroin opioids, says Caroline King, M.P.H.

Robert Feder, M.D., a psychiatrist in Manchester, N.H., and a member of APA’s Council on Addiction Psychiatry, said that this study demonstrates the effectiveness of treatment.

“These were pretty sick, relatively low socioeconomic status patients with significant substance use, and they clearly appeared to do better after the intervention,” said Feder, who was not involved in the research. “[The researchers] did some very complicated and robust statistical analysis of the data, and they did it in a way that they could tease out that these people really did do better.”

Feder noted that patients with SUD or alcohol use disorder must be connected with outside resources for treatment to be successful.

“It looked like the researchers had sufficient outpatient resources to refer these people to after they got out of the hospital,” Feder said. “There needs to be an agreement that outpatient treatment providers want to be on the referral list and are available, but that’s a problem in many treatment localities: A lot of them are full and can’t take any more referrals. That leaves the hospital teams in a tough spot if there are not enough people available to provide outpatient treatment. We need more substance use treatment clinicians.”

This study was supported by Oregon Health and Science University, CareOregon, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. ■

“Patterns of Substance Use Before and After Hospitalization Among Patients Seen by an Inpatient Addiction Consult Service: A Latent Transition Analysis” is posted here.