Antipsychotic Use in Young Children Declining, but Concerning Trends Remain

Abstract

Many U.S. youth appear to be prescribed antipsychotics without first receiving recommended psychosocial interventions, experts say.

While there are signs of progress in the efforts to scale back the number of U.S. children prescribed antipsychotics, challenges remain: Many children are taking these medications off label, in combination with other psychotropics, and often without first receiving psychotherapy.

Several antipsychotics have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in children; however, only aripiprazole (for irritability associated with autism spectrum disorder, or ASD, and Tourette’s symptoms) and risperidone (ASD irritability) are approved for children under 10. Studies have pointed to significant prescribing of antipsychotics in young children outside of these approved conditions, often in lieu of behavioral approaches, such as family-based psychotherapies, that are known to be safe and effective.

The off-label use of antipsychotics for young children is worrisome, given their many known side effects as well as still-unknown effects on development, noted Greta Bushnell, Ph.D., M.S.P.H. Bushnell was the lead author of a report in the Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry that examined antipsychotic prescriptions to young, privately insured children. She is an assistant professor of epidemiology at the Rutgers School of Public Health.

Older studies have shown that after peaking in the mid-late 2000s, antipsychotic use in young children started to decline. To examine if these trends have continued, Bushnell and colleagues looked at national data from a commercial health insurance claims database collected between 2007 and 2017. They focused on antipsychotic prescriptions to children aged 2 to 7 years.

During the study period, more than 300,000 antipsychotic prescriptions were filled for this age group. The analysis showed that prescription antipsychotic use grew from 0.27% of children in 2007 to a high of 0.29% in 2009, before continually declining over time to a low of 0.17% in 2017.

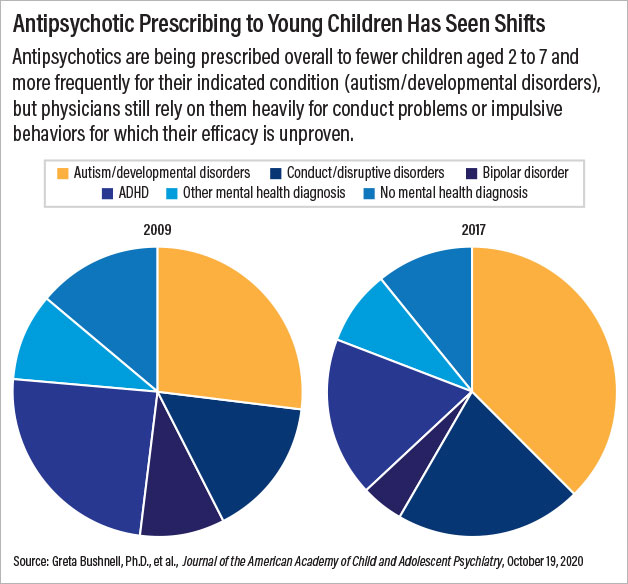

The study also found that these medications were being more frequently prescribed for indicated conditions such as irritability associated with ASD over time. In 2017, 37.6% of all children aged 2 to 7 receiving an antipsychotic prescription had ASD or a related pervasive developmental disorder, compared with 27.2% in the peak year of 2009.

Despite these reassuring findings, Bushnell noted that many young children continue to be given antipsychotics for conditions that are not supported by safety or efficacy data, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Even in 2017, 1 in 10 children given antipsychotics did not have any mental health diagnosis.

Bushnell’s findings also showed that only about 45% of the young children who received antipsychotics had claims for psychotherapy—a rate that has not changed since 2009.

And though fewer young children are receiving antipsychotics, the children getting them are more likely to be taking other medications as well; the number of children receiving polypharmacy (two or more psychiatric medications) rose from 81.7% to 86.4% between 2009 and 2017.

Young children aren’t the only ones being prescribed multiple psychiatric medications, according to a recent report in JAMA Pediatrics.

Chengchen Zhang, M.P.H., a graduate research assistant at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, and colleagues analyzed data collected between 1990 and 2015 from the Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys—an annual survey that tracks health care use and expenditures. The researchers specifically focused on the number of youth up to age 18 who received prescriptions for at least three classes of psychiatric medications over this period.

Zhang and colleagues found that youth treated with multiple psychiatric medications nearly tripled from the period of 1999 to 2004 to 2011 to 2015. Stimulants were the most common medication prescribed to these youth, as more than 80% of youth receiving polypharmacy had an ADHD diagnosis. The rise in polypharmacy was driven by antipsychotics; 38% of all youth receiving polypharmacy between 1999 and 2004 took antipsychotics, but this rose to 69% between 2005 and 2010 and to over 75% between 2011 and 2015. The number of children under 13 receiving polypharmacy appeared to decline by over 10% between 2005 and 2015.

“In looking over these studies, it does appear that doctors are still trying to hit disruptive and impulsive behaviors in children with medication after medication,” said W. David Lohr, M.D., an associate professor of child and adolescent psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Louisville School of Medicine.

“We all have probably encountered those difficult cases where young children’s behavior is so severe that they require medications for their safety, but [these] current data suggest young children are not getting the proven psychosocial interventions that they need,” continued Lohr, who was not involved in either study.

Bushnell agreed that psychotherapy needs to be addressed. “Guidelines recommend that psychosocial services are to be used before antipsychotic treatment,” she told Psychiatric News. Yet her findings showed that less than half of young children prescribed antipsychotics received psychotherapy. “We need to see this rate improve in the coming years.”

Bushnell’s study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Zhang’s study was supported by AHRQ. ■