From a National Election to an APA Election: A Lesson Learned

In the U.S. election this year, more Americans voted than in any previous presidential election. CBS News reported that as of November 30, both former Vice President Joe Biden with 80,120,249 votes (51.1% of the total) and President Donald Trump with 73,925,044 votes (47.2%) exceeded Barack Obama’s previous record of 69,498,516 votes in the 2008 election. Voter turnout was reported as 66.8% of eligible voters, the highest in 120 years. In 1900, William McKinley won reelection with a 73.7% turnout. The highest voter turnout in U.S. history occurred in 1876, when our 19th president, Rutherford Hayes, was elected to his one term in office with a voter turnout of 82.6%. The comparisons with these last two elections are not fair, however, as the pool of eligible voters consisted basically of White men.

U.S. Voting History

In 1776, voting was controlled by individual state legislatures; only White men who were age 21 and older and owned land could vote. The 14th Amendment, approved by Congress in 1866 and ratified in 1868, granted citizenship to all people “born or naturalized in the United States,” including former enslaved individuals, and guaranteed to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. In 1870, Congress passed the 15th Amendment, which stated that voting rights could not be “denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” But through such means as literacy tests, poll taxes, fraud, and intimidation, significant numbers of Black people were still effectively precluded from voting for close to another century.

In 1964, the 24th Amendment eliminated poll taxes, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 prohibited the states from using literacy tests and other methods that would result in excluding Blacks, or anyone else, from voting. This catapulted the percentage of Black people registered to vote from an estimated 23% to 61% in 1969. As the 2020 election illustrates, however, this hardly eliminated methods to interfere with elections.

Women got the right to vote with passage of the 19th Amendment by Congress in 1919 and ratification by the states in 1920. Achieving this milestone required organized efforts spanning over half a century. Most indigenous people in the United States were not given the right to vote until 1924, with the passage of the Indian Citizens Act.

In 1971 the 25th Amendment lowered the voting age to 18 years old. In 1975, the Voting Rights Act was amended to require bilingual elections in areas with large numbers of citizens with limited English skills, and in 1984, the federal Voting Accessibility for the Elderly and Handicapped Act required polling places to be accessible to people with disabilities.

The turnout in the 2020 presidential election represents a combination of many factors including the respective positions on important issues facing this country, the character and styles of the two candidates, their choice for vice president, and some unintended consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. Depending on where they lived, voters had the option of voting early or on election day or by ballots mailed to voters who could return them by mail or put them in drop-off boxes. A significant number of votes were cast before Election Day—more than 100 million—which was far in excess of prior national elections.

Will our country’s history and the circumstances surrounding our most recent national election affect the voter turnout in the APA election in January? It’s clear how hard we’ve worked as a nation, and are still working, to encourage Americans to register and vote and ensure their vote is counted. For most of us, voting in the APA election is easy. Every eligible voting member of APA has one vote, and no one needs to register. Do APA members vote?

APA Voting History

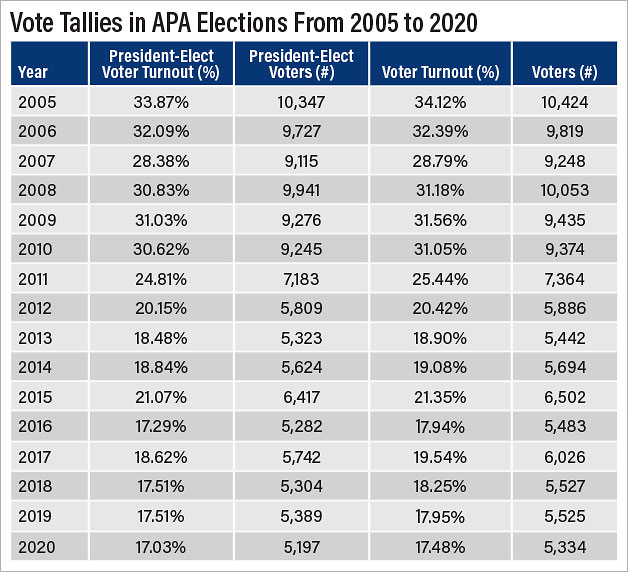

The history of APA’s elections shows progressively decreasing participation of APA voting members as indicated for the president-elect race and by the total votes cast in the table.

Earlier data indicate that in the 1970s, 50% to 60% of eligible voters voted, declining to about 40% by the 1990s. During this time, ballots were cast by mail.

While making it easier to vote in the 2020 national election appears to have resulted in more voter participation, ease of voting has not had a comparable effect on APA elections. In 2001, eligible voting members began to receive electronic ballots in addition to paper ballots. Beginning with the 2011 election, due to budgetary constraints, eligible voting members no longer received both electronic and paper ballots. All eligible voters with correct email addresses on file with APA receive only electronic ballots. Other voters receive a paper ballot.

By 2010 half of voters cast their votes electronically, and in 2020 that percentage increased to approximately 95%. During the same period, the percentage of APA voters who cast ballots decreased from 31.05% to 17.48%, the lowest percentage voter turnout in the past 16 years and probably ever.

The 2021 APA Election

Many of my predecessors have wondered in this column why voter turnout is so low in APA elections. None have come up with a satisfactory answer, nor do I have one. But some reasons endorsed by voters are all wrong. Among them: your vote doesn’t matter, the candidates’ positions don’t differ (“they all make roughly the same promises”), and members of the Board of Trustees don’t really influence what happens because “the staff make all the decisions.”

Here’s the truth: The Board holds the fiduciary responsibility for APA and approves the annual budget, focuses on APA’s priorities, and approves APA policy. The APA president, with the support of the other Board members, establishes special projects for the year. The CEO/medical director is hired by the Board and answers to the Board. The APA Assembly is advisory to the Board; the Board decides on the outcome of actions that come to the Board (usually through the Joint Reference Committee). The Board establishes dues. The Board can modify any council or committee. The staff executes much of the work of APA; the Board decides what that work will be.

It should not be hard to see how Board members affect not only APA, but also you as an individual member of APA, the field of psychiatry, and even medicine at large. For example, this year it was the Board that focused APA’s activities on structural racism (directly and through a task force), worked on a project to determine a psychiatric-bed need formula (through another task force), decided that the 2021 Annual Meeting would be virtual, and passed a significant number of position statements that impact your practice.

It’s not difficult to learn about the candidates, although live opportunities that existed in years past are not available this year. This issue of Psychiatric News includes the names, photos, and website addresses of the candidates. Each candidate participated in a virtual “Meet the Candidates” session.

Electronic ballots will be mailed to eligible voting members with a valid email address on file beginning January 4; reminders to vote will be sent through direct emails and the Psychiatric News Update and Alert. You can cast your vote anytime between January 4 and February 1. Paper ballots are available on request by sending an email to [email protected] and must be postmarked by the February 1 deadline. It’s not hard to vote and takes only a few minutes.

If every APA member who voted in the national election voted in the APA election, we would surely have a turnout that exceeds any in modern times. I hope this information about our nation’s and our Association’s voting history will move you to participate in dramatically reversing a trend in APA members’ participation in elections. Please join me and vote in the upcoming election—your vote really does matter. The 2020 national election should have certainly driven that point home! ■