Remember Books? Researcher Shows How Reading Is Superior to Screen Time

Abstract

John Hutton, M.D., who studies the effects of screen time on the developing brain, has penned several book series aimed at promoting early reading and reducing screen time.

It’s a scene that seems to come right out of a movie: An aspiring pediatric emergency physician takes time off during his residency to help care for his children and do a little writing on the side. Upon discovering that his neighborhood children’s bookstore is about to go out of business, he and his wife agree to purchase the establishment—signing the contract in green crayon to seal the deal.

The purchase was not the end of the story for John Hutton, M.D., however. After seven years of running Blue Manatee Bookstore in Cincinnati full time, Hutton returned to pediatric medicine—but switched his focus to screen time and literacy. Today, Hutton is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Cincinnati and director of the Reading and Literacy Discovery Center at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

Hutton’s research focuses on what goes on in the brain during the critical period of 3 to 5 years of age when children begin learning to read and to what extent screen-based media affect this early development.

Hutton was the lead author of a study published in JAMA Pediatrics in 2019 that used MRI scans to analyze the brains of 69 preschoolers. The analysis showed that children who used screen-based media more had less-developed white matter in brain areas important for language and literacy than those who used screen media less. White matter is the insulated nerve bundles that crisscross the brain and transmit information between different regions.

The finding that high levels of screen time might contribute to developmental delays is not new. Another 2019 study in JAMA Pediatrics by researchers at the University of Calgary suggested that children with higher than average screen time for their age group were slower at reaching key developmental milestones, such as walking on stairs or putting on their own clothes by kindergarten.

Hutton’s work, however, offers some of the first evidence that screen time might alter the brain.

Screen Time Involves Many Variables

“What we call screen time can encompass many different activities, and many previous studies, important as they are, have been limited because they focus on one variable, like TV in the bedroom,” Hutton told Psychiatric News. His study made use of a new composite scale he codeveloped known as ScreenQ. This scale factors in numerous aspects of screen time cited in the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines, including the types of devices used, where they are used, the frequency of viewing, the type of content, and whether parents are viewing with their children.

His findings reflect complex and increasingly nuanced aspects of media use that may have additive impact, such as initiation at earlier ages, contexts such as mealtimes or bedtime, and use of portable devices. Thus, even children whose parents choose media billed as “educational” (claims that are generally not supported by scientific evidence) might still be at risk of delayed brain development.

“There are fundamental realities about how a child’s brain develops, which have been shaped by millennia of evolution,” Hutton said. “Young children learn language from real people and not from a screen.” The other fundamental reality is that over the past couple of decades screen-based options have exploded.

“Television has been around for a while, but for most of its existence the TV set sat in one room and was often a social activity a family did together,” Hutton continued. “Today people hold devices more powerful than the computers that sent people to the moon.”

How Reading Changes Developing Brain

It was the rapid growth of mobile technology and experiences Hutton had as a father of three young girls that led him to return to medicine in 2008. After completing his pediatrics residency, Hutton began a fellowship at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. His foray into imaging research came after the American Academy of Pediatrics issued its first set of literacy guidelines in late 2014. “The guidelines referenced numerous studies related to reading and brain development, but I noticed that none of them were neuroimaging-based studies,” he said.

Wanting to address this gap, Hutton teamed up with colleagues in the Department of Pediatrics to assess the brain activity of preschool children as they listened to stories. The researchers found that children who spent more time reading at home with their parents had higher activity in a brain region called the parietal-temporal-occipital area. This region is considered a “hub” for integrating visual and language inputs to support comprehension, Hutton said.

A follow-up study found that when it comes to shared reading, using basic picture books provides optimal stimulation for toddlers. In this study, Hutton and colleagues performed MRI scans of children as they either listened to an audiobook, a book with static illustrations, or an animated book.

“We termed the results a ‘Goldilocks Effect,’ ” Hutton said. “Spoken words by themselves were associated with greater ‘strain’ in the children’s language pathways, while animation seemed to be overstimulating their visual networks.” Combining static pictures with words provided just the right visual-language integration at this age, he said.

Hutton admits that his work could be described as “using high-tech methods to verify the obvious,” but he thinks the findings reinforce the value of shared reading to provide nurturing experiences, which drives healthy brain development.

In recent years, Hutton has produced numerous children’s books aimed at promoting literacy and reducing screen time. His first set was a series known as “Baby Unplugged,” which celebrates simple childhood items—like blankets, blocks, and balls—using warm images and basic rhymes to nurture early language. Additionally, he developed a series of board books called “Love Baby Healthy,” which educate parents on such topics as infant calming and safe sleep in a format that can be read to babies. According to Hutton, these books have been distributed to millions of families, including through statewide campaigns.

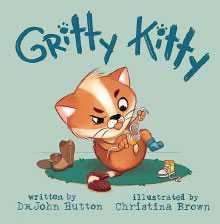

He has also developed books geared toward older children, including a book about resilience called Gritty Kitty and one about attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) titled ADHD-Me! Hutton noted that a typical conversation about ADHD involves the parent and doctor while the child is off in the corner, so he hoped to provide a means to bring the child into the discussion in an empowering way.

Given his recent productivity, it may be hard to envision that Hutton has only been a faculty member at Cincinnati Children’s for four years. “I’m 51 years old and just getting off to the races,” he joked. “I need to make up some time.”

As for the Blue Manatee bookstore that he had to sell in 2018? It ended up in good hands. The bookstore was purchased by a pair of entrepreneurs who converted it into a nonprofit organization called the Blue Manatee Literacy Project, which is dedicated to improving child literacy. The storefront still sells children’s books, and for every book purchased, another is donated to students in the Cincinnati area. ■

“Associations Between Screen-Based Media Use and Brain White Matter Integrity in Preschool-Aged Children” is posted here.

“Home Reading Environment and Brain Activation in Preschool Children Listening to Stories” is posted here.

“Differences in Functional Brain Network Connectivity During Stories Presented in Audio, Illustrated, and Animated Format in Preschool-Age Children” is posted here.