How Will AI Change Psychiatry?

Abstract

Artificial intelligence will likely lead to positive changes for psychiatrists and patients, but experts say it’s hard to envision the technology replacing psychiatrists.

The 1982 film “Blade Runner” envisioned 2019 as the year artificial intelligence (AI) would reach a zenith—complete with living, breathing, and dreaming robots that were indistinguishable from humans. While AI in 2019 was not quite at that level, its presence could be felt across industries, including the medical sector.

2019 in fact saw a couple of notable regulatory announcements related to medical AI. The Food and Drug Administration in April published a discussion paper describing a proposed framework for regulating AI applications, including machine learning software. In September, the AMA approved two medical billing codes for a pair of AI-guided retinal scans (these codes won’t take effect until January 1, 2021).

Although AI is becoming more common in digital-heavy fields such as ophthalmology and radiology, the application of AI in psychiatry to date remains limited.

“Machines can perform well in fields like radiology because medical scans are very pattern based,” said P. Murali Doraiswamy, M.B.B.S., a professor of psychiatry and medicine at Duke University School of Medicine who is exploring technology applications in dementia care. “Psychiatry is quite the opposite; it involves a highly personal and ever-changing interplay of culture, psychosocial stressors, and biology.”

Doraiswamy believes that AI software will help psychiatrists eliminate some administrative work because it can process information quickly (for example, helping pick the best antidepressant based on a patient’s medical history). But he argues that psychiatrists have specialized skills that machines likely cannot reproduce.

“Mental health relies heavily on the ‘softer’ aspects of medicine, such as building rapport with patients and picking up on subtle cues like body language,” said Ellen Lee, M.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, who is also examining how AI can assist in geriatric psychiatry.

Psychiatrists Divided on AI

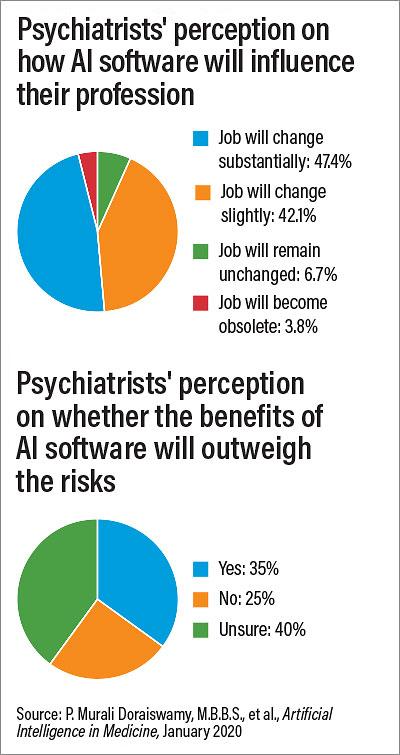

Psychiatrists are not of one mind regarding AI and its potential impact on the field, according to a survey conducted by Sermo in 2019 of 791 psychiatrists from 22 countries. The results (see chart) showed that psychiatrists were evenly split on whether AI would have a minimal or significant impact on their jobs within the next 25 years, though only a few were on the extreme ends (for example, 6.7% said AI would have no impact on their jobs, while 3.8% said their jobs would be obsolete). The survey respondents also had mixed feelings on whether the benefits of AI would outweigh the potential harms, including concerns over the privacy of patient data. Though more respondents than not believed the benefits of AI outweigh its risks, 40% were uncertain.

“I think this speaks to the importance of educating our field about both the strengths and limitations of this technology,” said Doraiswamy, who helped analyze the survey data.

“I think some of the uncertainty among psychiatrists about the impact of artificial intelligence arises because the term ‘AI’ is a bit misleading,” said Johns Torous, M.D., director of the Division of Digital Psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. AI applications in medicine primarily refer to machine learning programs—software that can quickly scan through reams of data and identify patterns and trends. The more data these programs receive, the better the software becomes at predicting these patterns.

“There’s nothing artificial going on; these programs use real data,” Torous explained. “And it’s not intelligence; these programs are only as powerful as the data they are trained on.”

Overcoming Machine Learning Limits

In psychiatry, a major focus of machine learning research is on predicting the onset of a disorder (will this person with acute psychotic symptoms develop schizophrenia?) or outcomes (is this person with depression likely to attempt suicide?). The machine learning software makes use of the robust patient data available in electronic medical records or research depositories, such as a gene bank, to provide a risk estimate.

“I see machine learning as providing an automated second opinion to a psychiatrist,” Brita Elvevåg, Ph.D., a professor of clinical medicine at the University of Tromsø in Norway, told Psychiatric News. But she also doesn’t envision a future where the software takes the place of the psychiatrist.

To make accurate predictions, AI software needs access to a lot of data, which is why many AI research studies involve organizations like Veterans Affairs or Kaiser Permanente that have linked, national databases. Even then, there are concerns about whether the patient data fed into an algorithm is generalizable to people of differing races, ethnicities, and socioeconomic backgrounds, Elvevåg continued.

For example, researchers in Sweden recently designed an AI-based application to distinguish and diagnose a range of dermatological conditions. The program was trained by scanning over 300,000 skin samples, but only about 5% of the samples were from people with a darker complexion. When the application was used to evaluate patients in Uganda, it failed to diagnose the conditions.

Elvevåg is working on a project even more challenging than matching skin discoloration to a skin disorder—developing speech-based biomarkers to identify potential mental illness.

“Speech offers a critical window into a person’s mental processes,” she told Psychiatric News. “Suicidality, depression, mania, delusions, hallucinations, Alzheimer’s, substance use, and a variety of other mental illness issues all change the delivery of speech.”

An effective speech-based diagnostic would have to identify subtle differences in impairment caused by each of the above conditions, while also considering that most patients would likely have multiple disorders that contribute to incoherent speech (like depression and substance use).

“So, to get an algorithm that can answer a specific question like ‘Does this speech pattern indicate psychosis?’ and make the algorithm applicable to every potential patient is difficult,” she said.

Lee also believes that wide variation in diagnosis and symptomatology of psychiatric disorders may limit how much machine learning can improve efforts to diagnose patients. She thinks there might be more value in using machine learning to look within individuals as opposed to across individuals.

“Over time, we can assess each person’s patterns with wearable devices, and we can identify changes in sleep or other parameters that suggest something is amiss,” she said. That’s why she is hopeful that AI could be valuable in geriatric psychiatry, as older people have a longer history of data for machine learning to analyze.

Looking at individual data also comes with caveats, noted Torous. “Context is critical when looking at real-time data, and machines cannot factor that in.” He provided an example from a mobile application he helped develop called mindLamp, which collects mood assessments in real time. One patient using mindLamp reported a significant uptick in depression shortly after switching medications—which was immediately flagged by the program. A discussion with the patient revealed that his medication switch occurred shortly before his mother became ill and that her illness triggered feelings of depression and anxiety.

That’s why Torous believes the best application of AI is as a conduit to bring patients and doctors together. “If I receive some unusual readings on mindLAMP, I would show it to the patient at our next meeting and ask, “Does this look right to you? Let’s talk about this—let’s use some real intelligence.” ■

“Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Psychiatry: Insights From a Global Physician Survey” is posted here.