ACA Celebrates 10 Years: Despite Effectiveness, Law Has Been Target of Dismantling

Abstract

A number of research studies have demonstrated a clear benefit of the Affordable Care Act for people with mental illness and substance use disorders.

President Barack Obama signs the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act on March 23, 2010.

Ten years ago on March 23, health care history was made when President Barack Obama signed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

Two days before, the House had approved the bill by a vote of 219-212.

Debate leading up to passage of the ACA was contentious; the changes the new law required were dramatic, capping decades of debate and discussion about how to achieve universal access to health care while containing skyrocketing costs. The most prominent changes mandated by the law were these:

Expanding insurance coverage to 30 million Americans, principally by extending Medicaid coverage (in states that chose to do so) to 133% of the federal poverty level, but also through the establishment of health insurance exchanges for individuals and small group coverage.

Requiring employers to cover their workers, or pay penalties, with exceptions for small employers.

Subsidizing insurance costs for low-income families.

Permitting dependents to be covered on parents’ insurance to age 26.

Barring coverage exclusions based on pre-existing conditions.

Preventing insurers from dropping enrollees who become ill.

Banning lifetime coverage limits and strictly limiting annual coverage limits.

Requiring individuals to have insurance, with some exceptions, such as financial hardship or religious belief.

The reform package also included a number of elements related to psychiatric care: coverage for treatment of mental illness, including substance use disorder (SUD), is required in the basic package of all plans marketed in the exchanges (as well as individual and small market plans outside of the exchanges), and federal mental health parity regulations apply to those plans. Medicaid expansion extended care to some of the most seriously mentally ill people while also closing (but not eliminating) the so-called Medicare Part D “donut hole.” That term applies to the gap in Part D prescription drug coverage for those beneficiaries with very high prescription costs; that gap has been narrowing each year since passage of the ACA and is scheduled to be eliminated entirely this year.

Substance Use Treatment Increases After Medicaid Expansion

Admissions to specialty treatment programs for substance use disorder (SUD) increased significantly in the period following state expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), according to a report last month in Health Affairs.

“The ACA Medicaid expansion was designed to improve access to care for poor, uninsured Americans and to reduce financial barriers to care,” wrote Brendan Saloner, Ph.D., of Johns Hopkins University and Johanna MacLean, Ph.D., of Temple University. “Our study suggests that the expansion achieved both of these objectives for people who received care in specialty SUD treatment programs.”

They used national admissions-level data from 2010 to 2017 from the Treatment Episode Data Set: Admissions, a federally mandated database for all specialty health care professionals who accept public funding or are otherwise subject to state regulation.

There were 11,205,670 admissions overall. Saloner and MacLean calculated admissions per state population in several categories per 100,000 nonelderly adults.

They also calculated the population rate of admissions by treatment setting: residential treatment, intensive outpatient treatment, and nonintensive outpatient treatment (outpatient treatment that either lasts less than two hours a day or occurs on fewer than three days of the week). They excluded admissions to detoxification programs, as this modality is not considered treatment on its own. The primary outcome was differences in treatment utilization between expansion and nonexpansion states before and after expansion.

They found that admissions to treatment steadily increased in the four years after Medicaid expansion, with 36% more people entering treatment by the fourth expansion year in expansion states compared with nonexpansion states. Changes were largest for people entering intensive outpatient programs and those seeking medication treatment for opioid use disorder. The share of admissions paid for by Medicaid increased 23 percentage points in expansion states compared with nonexpansion states, largely displacing treatment paid for by state and local governments.

“Overall, we find that the ACA Medicaid expansion increased the number of people receiving any treatment for opioid use disorder,” Saloner said in comments to Psychiatric News. “This occurred both for treatment that included and did not include medication. In some, but not all, years, we see faster growth in the expansion states in treatment with medications. An important caveat is that we do not know whether this was treatment that was comprehensive and whether it included other effective services such as counseling.”

He said the study was confined to looking at Medicaid expansion but added that he believes the health exchanges and parity requirements in employer-provided insurance “have been an important pathway into service for privately insured patients.”

Saloner also said that despite legal challenges, the Medicaid expansion has largely continued under the Trump administration. “It has actually grown, due to some more states joining the program since 2017, such as Maine and Idaho.”

He concluded: “I think the ACA Medicaid expansion has been really important not only to patients but also to state and local governments. One of our main points is that we see a lot of reduced spending by these governments, because Medicaid is now paying for the care of many previously uninsured individuals.”

The ACA also increased funding for community mental health centers, ensured that patients with psychiatric illness could not be excluded from “medical home” demonstration projects, permitted demonstration projects for co-location of primary and behavioral health care services, and authorized grants to establish “depression centers of excellence.”

Almost no one—including APA—was wholly satisfied with the law. One principal concern at the time was the law’s creation of an Independent Medicare Payment Advisory Board, which would make recommendations about containing Medicare costs (it was repealed before ever taking effect). The law also left intact the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula for physician payment and the discriminatory Medicare copayment for psychiatric services. The SGR was repealed in 2015 by the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act, and Medicare’s discriminatory payment was eliminated entirely in 2014.

“The passage of health reform is an important event, but it is really a beginning, not an end,” said APA Medical Director James H. Scully Jr., M.D., at the time. “Many critical details need to be addressed. … So while we are aware of the historic action that has occurred, there is now an enormous task ahead.”

In a column in Psychiatric News, then-APA President Alan Schatzberg, M.D., wrote, “Is the new law perfect? Of course not, but no law is. … On balance, however, the positives far outweigh the negatives, which is why APA supported passage.”

Law Increases Access to SMI, SUD Care

Imperfect as it was (and remains so to some people of all political persuasions), there is clear evidence that the law has been an enormous benefit to patients with mental illness—especially those with serious mental illness (SMI)—and more gradually, over time, to patients with SUDs.

A 2016 report in Health Affairs by Timothy Creedon, Ph.D., and Benjamin Le Cook, Ph.D., of the Cambridge Health Alliance found that mental health treatment rates increased significantly in 2014 compared with years prior to the implementation of insurance reforms in the ACA. The researchers looked at four time periods (2005-2007, 2008-2010, 2011-2013, and 2014).

“Among those meeting criteria for serious psychological distress in the past year, survey respondents in 2014 were significantly more likely to receive mental health treatment than respondents in any of the pre-2014 comparison periods,” they wrote.

A troubling finding was that the racial and ethnic disparities in access to care and treatment utilization persisted; nonwhite respondents did not experience the same increase in utilization as did whites. But Creeden and Le Cook cited several mitigating factors, including a 2012 Supreme Court decision that made Medicaid expansion voluntary, and several states—including those with some of the poorest populations—did not opt to expand.

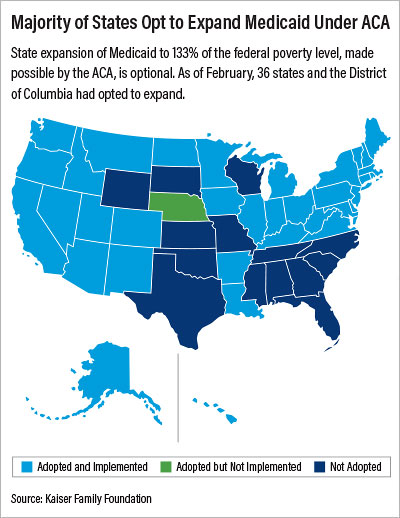

A Kaiser Foundation report found that as of February, 37 states and the District of Columbia opted to expand their Medicaid programs. Fourteen states have not: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming (see chart; Nebraska has opted to expand but has not yet done so).

Another 2016 report in the Journal of Rural Health found that among 39,482 young adults aged 18 to 25 years with psychological distress, adjusted insurance rates increased from 72.0% to 81.9% between 2008 and 2014, though a significant rural/urban difference remained in 2014. Treatment rates for those with psychological distress increased following 2010 reforms, from 30.2% to 33.0%. (Those treatment gains were not sustained into 2014.)

In an ACA anniversary edition of Health Affairs, Brendan Solaner, Ph.D., and Johanna Catherine MacLean, Ph.D., of Temple University found that admissions of individuals for treatment of SUDs steadily increased in the four years after Medicaid expansion, with 36% more people entering treatment by the fourth expansion year in expansion states compared with nonexpansion states (see box).

Challenges to the ACA

Since its passage, the ACA has been the target of Republican congressional attempts to scale back or eliminate the law entirely, court challenges to its constitutionality, and attempts by insurance companies to circumvent the parity requirements. A string of court rulings and settlements with state attorneys general or with state insurance commissions in Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania has compelled health plans to comply with the law.

Most recently, five major health insurers and two managed care companies in Massachusetts agreed to reverse practices that discriminate against patient and mental health professionals and restrict access to care, following a landmark settlement with the Massachusetts attorney general (see Psychiatric News).

Court challenges to the ACA have focused especially around the “individual mandate.” That provision in the original law levied a penalty on individuals who did not sign up for insurance in the exchanges; the mandate was designed to protect insurance companies against the enrollment of individuals who were sicker and were high service utilizers.

In December 2019 a panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit, ruling in the case Texas, et al., v. United States of America, et al., and California, et al., agreed with a district court in Texas that ruled in 2018 that the mandate was unconstitutional. That same district court also ruled that since the mandate was integral to the law, then the entire statute was rendered illegitimate; the court of appeals did not uphold that finding.

The case is before the Supreme Court, and Democrats in Congress and several states have asked the court to expedite review. Without comment, the Supreme Court declined to expedite, and any final ruling is likely to be months away (see Psychiatric News).

In the meantime, there is no question that the ACA has been transformative. Virtually the entire medical community has united behind its preservation. In December 2018, APA joined the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American College of Physicians, and the American Osteopathic Association in denouncing the Texas district court decision.

“As frontline physicians who care for patients in rural, urban, wealthy, and low-income communities, we call for immediate appeal of the decision,” the organizations said in a statement. “In addition, we urge the U.S. Congress and states to stand in strong support of protecting patient access to comprehensive health insurance coverage and join us in advocating for swift appeal. Finally, we urge the administration to continue implementing the law so our patients can continue receiving the care they need. Our message is simple: No one should lose the coverage they have.” ■