Supportive Psychotherapy

Abstract

Supportive psychotherapy was developed in the early 20th century as a treatment approach with more limited objectives than psychoanalysis, which had previously been the only psychological treatment in the field of medicine. Personality change and exploration of unconscious conflicts were the focus of psychoanalysis and expressive or exploratory psychotherapy. The objectives of supportive psychotherapy were not to change a patient’s personality or to explore conflicts, but rather to help a patient cope with symptoms, to prevent relapse of a serious psychiatric illness, or to help a relatively healthy person deal with a transient problem.

Based on these objectives, the definition of supportive psychotherapy most commonly used, as you’ll see in the new book of which I am co-editor, is “a dyadic treatment that uses direct techniques to ameliorate symptoms and maintain, restore, or improve self-esteem, ego functions, and adaptive skills with a focus on the patient’s overall health and well-being.”

Therapeutic Alliance

The key to successful results in all forms of psychotherapy is the establishment and maintenance of a positive therapeutic alliance between the patient and therapist. The therapeutic alliance is the best predictor of outcome in multiple psychotherapy studies. In the presence of a positive patient-therapist relationship, the patient is more likely to see himself or herself as a partner in the psychotherapy process. A positive therapeutic alliance furthers the patient’s interest in and commitment to the psychotherapy.

Psychopathology–Impairment–Psychotherapy Continuum

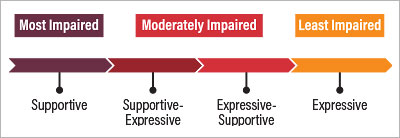

The psychopathology continuum and the supportive-expressive continuum are useful ways of conceptualizing the evaluation and treatment process to decide on the appropriate approach for a given patient. The psychopathology-impairment continuum begins with the most impaired patients on the left side of the continuum, moving to moderately impaired patients in the middle, to least impaired on the right (see figure). The supportive-expressive continuum conceptualizes psychotherapy on a continuum beginning with supportive psychotherapy on the left side, moving to supportive-expressive psychotherapy, then expressive-supportive psychotherapy, and finally expressive psychotherapy and psychoanalysis on the right side.

Supportive psychotherapy is indicated for patients on the left side of the continuum (higher impairment levels), whereas expressive psychotherapy is better suited for patients on the right side of the continuum (healthier patients). However, it has been shown that healthy patients can significantly benefit from supportive psychotherapy.

Evaluation Process

The evaluation process is a critical beginning to the psychotherapy process. Using the psychotherapy continuum, the initial determination as to the level of the patient’s impairment and functioning leads to the determination of the appropriate psychotherapy. Therefore, it is necessary to perform a thorough evaluation and assessment of the patient, including a case formulation and diagnosis, as well as setting the goals of the psychotherapy together with the patient.

Techniques

Once the treatment begins, the therapist must use the appropriate supportive psychotherapy techniques or interventions. There are many supportive psychotherapy techniques that maintain and enhance the therapeutic alliance and help to achieve the objectives of supportive psychotherapy. These include alliance building, esteem building, skills building, and enhancing ego function, such as frustration tolerance and coping skills.

Alliance building occurs when the therapist expresses interest, empathy, and understanding. Esteem building is enhanced through praise, reassurance, normalizing, and encouragement. Skills building and promoting adaptive behavior are objectives that respond to advice, teaching, modeling adaptive behavior, anticipatory guidance, and promoting autonomy. Enhancing ego function can be achieved by reducing and preventing anxiety and expanding awareness.

Additionally, anxiety can be reduced through the use of a conversational style, sharing the agenda with the patient, verbal padding, naming the problem, normalizing, rationalizing, modulating affect, supporting defenses, and limit setting. Expanding awareness can occur through clarification, confrontation, and interpretation.

Using these techniques requires skill and sensitivity on the part of the therapist. For example, when offering praise, the therapist should praise only patient behavior that is praiseworthy. Advice and teaching are only appropriate where the therapist is professionally expert. The use of confrontation does not imply hostility; it simply brings to the patient’s attention ideas, feelings, or a pattern of behavior that he or she has not recognized or has avoided and defended against.

General Considerations

Supportive psychotherapy is generally indicated for almost all psychiatric diagnoses. As with other psychotherapies, it is not indicated for antisocial personality disorder unless the patient has another diagnosis, such as depression. Supportive psychotherapy is often combined with medication and is necessary for patients with significant depressive symptoms, psychosis, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and the like. There is no fixed time interval. Patients can be seen weekly, every other week, or less frequently depending on their needs. Therapists should be flexible with regard to the frequency of psychotherapy sessions and the length of a psychotherapy session. However, personal boundaries between patient and therapist must be maintained. Supportive psychotherapy can also be combined with cognitive-behavioral therapy, especially to address symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Outcome studies of supportive psychotherapy have found it beneficial for many diagnostic entities, including anxiety and depressive disorders, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, personality disorders, eating disorders, and physical illnesses.■