Antipsychotics Increasingly Prescribed for Bipolar Disorder

Abstract

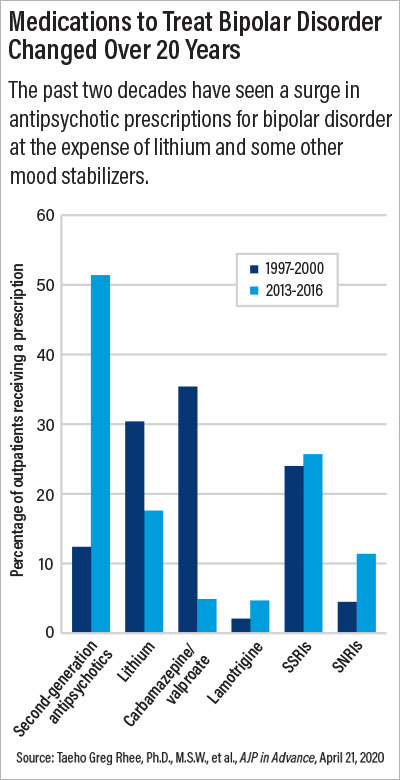

More than half of outpatients with bipolar disorder received a second-generation antipsychotic in 2016, up from 12% just 20 years ago.

Over the past 20 years, a growing number of patients with bipolar disorder have been prescribed antipsychotics, as the number of prescriptions for the mood stabilizer lithium—considered a gold-standard treatment—have dropped. This uptick in antipsychotic prescribing is not surprising given that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved multiple antipsychotics for bipolar disorder during the last two decades. An analysis reported in AJP in Advance now quantifies this national paradigm shift.

Investigators at Yale University School of Medicine and colleagues examined data from the 1997-2016 National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys, an annual questionnaire completed by a nationally representative sample of office-based physicians.

The sample included 4,419 outpatient visits to a psychiatrist by a patient diagnosed with bipolar disorder; this represents over 4 million visits nationally over the 20-year period, according to the authors. The total number of visits per year rose over time, with about 467,000 visits occurring between 1997 and 2000 and 1.06 million visits occurring between 2013 and 2016.

As the number of visits for bipolar disorder rose, so did the use of second-generation antipsychotics; 12.4% of all outpatient visits in 1997 included second-generation antipsychotic prescriptions, compared with 51.4% of all visits by 2016. Visits for bipolar disorder that included prescriptions for lithium dropped from 30.4% to 17.6% during this same period, while prescriptions for any mood stabilizer (which includes carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and valproate) decreased from 62.3% to 26.4%.

The analysis revealed that the largest surge in antipsychotic use occurred between 2000 and 2008—a time in which five antipsychotics received FDA approval for bipolar disorder (aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone). Overall prescribing rates have remained stable since then.

“This study highlights how targeted marketing can make a loud splash in an area where there is not a lot of data,” said Michael Ostacher, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University, who was not involved with the study.

He noted that for decades bipolar patients were limited primarily to lithium as a treatment option. This medication is effective at controlling manic episodes, but it can take a while to reduce symptoms, and it comes with some medical risks. These include toxicity when lithium levels become too high and/or thyroid and kidney damage from long-term use. (Patients on lithium are required to have regular blood tests to monitor lithium levels.)

“Lithium also has some common ‘nuisance’ side effects such as acne and hair thinning,” added Benjamin Goldstein, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto and director of the University’s Centre for Youth Bipolar Disorder. Goldstein was not involved with the study. Such side effects may be particularly off-putting for teens and young adults—the age group in which bipolar symptoms typically manifest, he said.

In addition, there was a belief among some in the psychiatric community that lithium was not well suited for some patients, such as those who experience mixed bipolar episodes (depression and mania at the same time), Ostacher said.

Pharmaceutical companies marketed antipsychotics to doctors as possessing numerous benefits over lithium and other mood stabilizers; these drugs could offer rapid relief of manic symptoms with less stringent blood test requirements. “On top of that, the United States has the phenomenon of permitting direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription products,” added Taeho Greg Rhee, Ph.D., M.S.W., an assistant professor of medicine and public health at Yale and lead author on the study. That amplified the message being sent to physicians and enabled antipsychotic use to take off.

Since lithium and bipolar disorder have been so closely linked for decades, many patients might conflate the medication with the negative stereotypes about bipolar disorder, noted Goldstein. “A young person might remember a grandparent with bipolar who had to be hospitalized because of severe mania and be wary of lithium.” These new medications did not have such historical baggage and were appealing to many patients, he said.

Ostacher added that the role of marketing was not limited to antipsychotics. The mood stabilizer valproate also experienced an uptick in use for a few years after it was approved by the FDA in 1995, but valproate prescriptions have since declined, likely due to studies showing that this drug may pose health risks during pregnancy, he said. “[S]econd-generation antipsychotics also have several health warnings clearly printed on their labels yet remain widely prescribed for bipolar despite no demonstrated evidence that they are superior.”

Ostacher highlighted the risk of antipsychotic-induced weight gain as especially concerning in light of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. “Hospital data show that people with obesity and diabetes are at higher risk of severe COVID symptoms, so psychiatrists should consider that when prescribing antipsychotics.”

Rhee noted that more rigorous head-to-head research is needed to see how lithium, antipsychotics, and other bipolar medications stack up, especially in relation to long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes, including suicide risk.

In addition to studies, Ostacher—who admits to being a big fan of lithium—suggests this medication needs more champions in the field to highlight the medication’s benefits and dispel some of the myths that it doesn’t work in certain patients. Goldstein added that training programs should ensure that psychiatry residents are effectively trained about lithium and its potential risks, so they can feel comfortable prescribing it early in their careers.

In a study that was heavily focused on medication data, one of the most disconcerting findings to Goldstein, however, was the marked reduction of patients on medication who also received psychotherapy; rates dropped from 50.9% of patients in 1997 to 35.7% in 2016.

“Psychotherapy not only helps with bipolar symptoms but also encourages better nutrition, exercise, sleep, and medication adherence,” he said. “We can debate the relative benefits of mood stabilizers and antipsychotics, but no medication will keep a patient organized and motivated; we need psychotherapy for that.”

This study was supported by multiple grants from the National Institutes of Health with additional support from the Dauten Family Center for Bipolar Treatment Innovation, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, Robert E. Leet and Clara Guthrie Patterson Trust, and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. ■

“20-Year Trends in the Pharmacologic Treatment of Bipolar Disorder by Psychiatrists in Outpatient Care Settings” is posted here.