Innovative Suicide Prevention Program Using Psychotherapy Shows Early Success

Abstract

Dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy is designed to reroute the processing of emotions and experiences through the prefrontal cortex, where they can be translated into language.

Multiple hospitalizations, previous failed therapies, suicidal thoughts, episodes of self-harm, and suicide attempts.

These were the common features in a cascade of trouble that brought “Melissa” and “Allison” (not their real names)—two young women in their 20s who shared their stories with Psychiatric News—to the Psychiatry High Risk Program at SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, a year-long comprehensive treatment program.

After multiple trials of failed treatments, both women immersed themselves in the program’s manualized therapy known as dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy (DDP).

Robert Gregory, M.D., says outcome data from the psychotherapy program have earned it recognition from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

DDP, developed by Robert Gregory, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at SUNY Upstate, focuses on “deconstructing” the negative self-image and maladaptive patterns of responding to charged experiences that patients bring to therapy. Drawing on translational neuroscience and object relations theory, the therapy explicitly avoids “crisis management” in favor of working toward more fundamental changes in neural pathways.

These changes allow patients like Melissa and Allison to see themselves, their relationships, and their place in the world in a new, empowering way. “The therapy helped me see myself in a different light,” said Allison, whose history included homelessness and placement in a woman’s shelter after a period of family discord. Today, she is enrolled in college and living independently and continues to see her therapist for monthly visits.

Melissa is a shift manager at her job. She recently got a driver’s license and has her own apartment. She credits DDP with a crucial, life-saving change: “This time last year, I was three months into DDP, three months free of self-harm in my year eight-year battle with self-harm,” she told Psychiatric News. “Never would I have thought this time last year that I would be where I am today.”

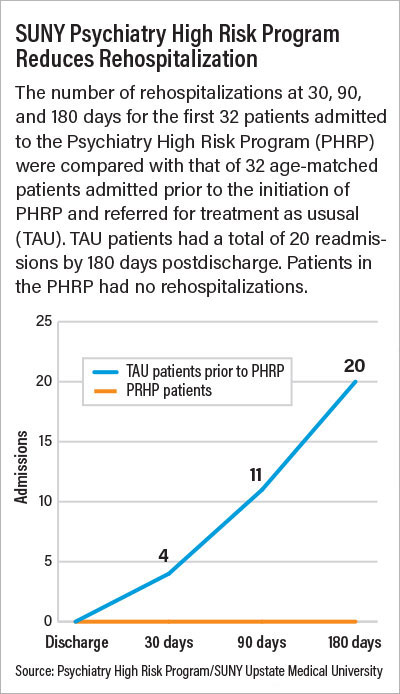

The Psychiatry High Risk Program (PHRP) has carefully tracked outcomes for 216 patients who have enrolled in the program since its inception. They have shown dramatic improvements in suicidal ideation, depression and anxiety, and substance use. Patients in the program have also seen significant decreases in rehospitalization and emergency department use (see chart).

The program’s success has been recognized by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Gregory noted.

“It’s not about solving crisis after crisis, which has often been patients’ experience in therapy before,” Gregory said in an interview. “To help patients be free from depression and suicidal thinking and to be able to form meaningful relationships, we aim to inject hope by opening up new ways of experiencing, perceiving, and relating to oneself and others.

“For many patients, this is really transformative, a radically different way to approach their problems.”

Treatment Programs for Suicide Risk Are Rare

The PHRP at SUNY Upstate was initiated in 2017 in response to the twin crises of rising suicide rates among young people and diminishing availability of services. A press conference at the medical center that year to address the problems brought together U.S. Rep. John Katko (R-N.Y.), New York State Assemblyman Bill Magnarelli, leadership at SUNY Upstate, and the parents of a Syracuse area woman who died by suicide at age 16.

One outcome was the creation of the Youth Mental Health Services Task Force, to which Gregory was appointed, charged with looking at regional services for young people, especially the lack of inpatient beds. Gregory said the task force also highlighted a dearth of step-down programs, day hospitals, and specialty outpatient care. “Interventions for suicide prevention have been almost entirely about education, research, and outreach,” he said. “Treatment programs are surprisingly rare.”

In response, Gregory—a psychotherapist with an interest in the neuroscience of how emotions are processed through neural networks—developed the Psychiatry High Risk Program, incorporating DDP. (Gregory had already developed the therapy and published papers on its theory and application.)

He explained that DDP is designed to address two causal mechanisms common to young adults struggling with suicidal thinking: aberrant emotion processing and an embedded “sense of badness.” DDP counters these ingrained traits not (as in many manualized treatments) by teaching new coping mechanisms or problem-solving skills or (as in traditional psychoanalytic therapy) recounting traumas or interpreting patients’ defenses.

Rather, he said, the goal is to help patients connect with and verbalize their experiences. This enables them to think about those experiences in new ways and develop alternative ways of relating to others. The therapy especially utilizes “autobiographical memory” whereby patients practice recounting specific interpersonal encounters and constructing a narrative and “affect labeling,” an exercise in identifying and naming feelings.

“Neuroscience is converging around the mechanisms of aberrant emotion processing,” Gregory said—specifically the way life experiences and the emotions associated with them become processed in high-risk patients through subcortical structures in the brain, resulting in hyperarousal; mood lability; and impulsive, reactive responses. These can cause patients to spiral quickly into despair, self-destructive behaviors, and suicide, Gregory said.

The work of patients in DDP reroutes those processes through the prefrontal cortex, where experiences and emotions can be translated into language. Gregory likens it to physical and occupational therapies that help stroke victims revitalize muscles and motor neurons that have atrophied. “That’s how I look at successful psychotherapy—strengthening neural pathways and building new synapses and even new neurons,” he said.

He added, “Everything we are doing at the PHRP is reproducible, and I hope other medical centers will create their own treatment programs for high-risk patients.” (Information about PHRP and DDP, including training resources and published research, is posted on the SUNY Upstate website; see end of article for information.)

Jeffrey Smith, M.D., the new head of the APA Caucus on Psychotherapy, says the ability to map the processes of psychotherapy to changes in neural networks is key to demonstrating the efficacy and efficiency of psychotherapy.

“Translational neuroscience has made important strides in understanding how the mind works so that we can look at the sources of trouble for which psychotherapy is the most accurate and powerful tool that we have,” Smith told Psychiatric News. “With appropriately placed words, we can activate a few hundred neurons rather than asking patients to take a medication that affects millions of neurons.”

‘It’s Intense but It Really Works’

That ability to verbalize feelings rather than only act on them is transformative in the stories of the women who spoke with Psychiatric News.

“Talking to my therapist really helps me figure out what it is I am feeling and work through those emotions,” said Allison. “I have really intense emotions that can make my relationships unstable, and sometimes it’s hard for me to talk about my own mental distortions. It’s intense but it really works.”

Melissa echoes those words. “DDP has a specific approach that works well with people like me who have difficulty identifying emotions. Having to really pinpoint emotions helps me understand why I feel the way I do and think about things differently.” Even in the midst of lockdown brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, both women—who testified to having experienced the darkest despair—are remarkably stalwart, looking with hope to the future.

“I had always felt hopeless for a really long time,” Melissa said. “I didn’t want to live anymore, and I had those feelings every day. This therapy changed my life.” ■