Structural Racism in American Psychiatry and APA: Part 1

Abstract

This article covers October 12, 1773, to June 12, 1862.

Cup Foods, on the corner of 26th Avenue South and East Lake Street in Minneapolis, is a neighborhood grocery store. On May 25, George Floyd, a regular at the store, got more than the pack of cigarettes he went in to buy. Minneapolis police officers served death to George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man, who, in all likelihood, unknowingly paid for his cigarettes with a counterfeit $20 bill. And then the cycle repeated with the murder of Rayshard Brooks.

After Floyd’s murder, you participated in or read about protests that occurred not only from coast to coast, but also worldwide. Surely you have received an email from every organization to which you belong, and probably just as many to which you don’t, expressing their outrage. It’s the thing to do. What will people think if some organizations don’t do it? What’s worse, all manner of commercial enterprises have spewed out their chagrin. If they all meant what they said, they’d do something, such as have fair and transparent background checks for Black workers and pay them equitable wages with good benefits.

Where does APA fit into the latest lethal reminder that racism is still rampant and that, as Al Sharpton stated at Floyd’s memorial, “Time is out for empty words and empty promises”? And where does APA go from here? To better answer these questions, it’s helpful to know where we’ve come from.

18th Century

The history of American psychiatry and the history of Black Americans is the history of slavery and segregation in America for over 200 years, right on through the end of the Civil War; the passage of the 14th and 15th Amendments; the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which included a provision for equal access to public places; and up to the present. The history of American psychiatry and segregation extends well into the lifetime of over 100 million Americans living today.

On October 12, 1773, the Public Hospital for Persons of Insane and Disordered Minds in Williamsburg, Va., the first public freestanding psychiatric hospital in British North America, admitted its first patients. From its opening through the 19th century, the relationship between the hospital and Blacks is both remarkable and perplexing. Unlike most of the hospitals that were later built in the South, the Williamsburg asylum admitted both free Blacks and enslaved Blacks and housed them in the same hospital building. However, enslaved people could be admitted only if their admission did not interfere with the admission of a white person, and their care had to be paid for by their owners. Moreover, the asylum needed slave labor to operate and paying patients to make ends meet. So the Williamsburg asylum accepted slaves in payment for care and treatment and advertised this fact.

John Minson Galt, who was the physician head of the asylum from 1841 to 1862 and one of APA’s founders, did not expect many Blacks to present for admission. Insanity was thought to be a disease of civilized people, and Africans and their descendants were considered a “primitive” population. The assumption of the time was that enslaved people lived a simple life in which decisions were made for them, while white people were exposed to the stress and strain of daily decision making about property, business, education, religion, and health care. Galt thought Blacks were “immune” to insanity “because they are removed from much of the mental excitement to which the free population is necessarily exposed in the daily routine of life.” Such beliefs expose the ignorance of white psychiatrists. How could they think that living a life in which you were owned by someone who could sell your family on a whim, who could punish you for anything he decided was a transgression, who could prohibit you from practicing customs and a religion of your choice, and who controlled every aspect of your living conditions was stress free?

In 1792 Benjamin Rush, considered the father of American psychiatry and the best known physician throughout America in his era, was a remarkable mix of contradictions. He was an ardent abolitionist who owned a slave. He spoke out on the position that Blacks were of equal intelligence and morality as whites. He proclaimed that Black skin was actually a disease, and in support of his belief, Rush produced a Black man who was turning white. A contemporary explanation for this is that this man had vitiligo. Rush prescribed scrubbing the skin long and hard.

The 1840s

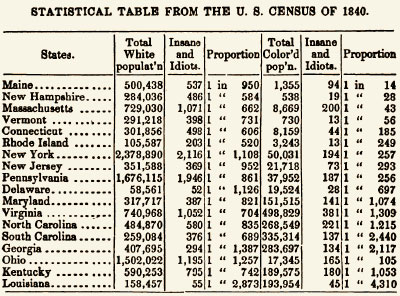

The U.S. census of 1840 brought to the nation’s attention the relationship between slavery and insanity. The census had a new category that year: “insane and idiotic.” The census reported that in free states, there was one insane or idiotic person for every 144.5 Blacks; the ratio for whites was 1 to 867. However, in slave states, the ratio of insanity for Blacks was 1 to 1,558. Also, the farther north one went, the higher the ratio of insanity in Blacks, and the farther south one went, the lower the ratio. The ratio of insanity among Blacks in Maine was 1 in 14, while in Louisiana the ratio was 1 in 4,310. John McCune Smith, the first Black licensed to practice medicine in the United States, and Edward Jarvis, a physician and father of American biostatistics, wrote scathing rebuttals highlighting fundamental methodological flaws. John C. Calhoun, who had resigned his position as vice president to become a senator from South Carolina, supported the findings of the census, proclaiming, “Here is the proof of the necessity of slavery. The African is incapable of self care and sinks into lunacy under the burden of freedom. It is a mercy to him to give this guardianship and protection from mental death.” John McCune Smith’s conclusion was different: “Freedom has not made us mad; it has strengthened our minds by throwing us upon our own resources.”

In the wake of the 1840 census, APA—named at the time the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane—was formed when Samuel Woodward of Worcester, Mass., and Francis Stribling of Staunton, Va., convened a meeting of 13 superintendents. All these alienists came from freestanding psychiatric hospitals, some public and some private. General medical hospitals wanted to segregate patients and could do so by placing them in separate rooms or wards. At least one of the superintendents at that meeting believed the country needed to have hospitals where only white patients were treated. From his point of view, segregating sections of an asylum was unacceptable. This issue arose concurrently with the spread of Moral Treatment. Moral Treatment included the concept that patients of higher social status should not be caused distress by having to associate with patients of lower social status. That lower class group, of course, included Blacks.

This table appears on page 155 of the October 1851 issue of the American Journal of Insanity in the article titled “Startling Facts From the Census.”

Of the original 13 members of APA, most were from New England or New York. One of APA’s founding members was an ardent segregationist who felt admitting Blacks to his hospital was repugnant. That psychiatrist was Francis Stribling from western Virginia. The most active voice in favor of integrated facilities was John Galt from eastern Virginia. Some superintendents endorsed segregation by using different buildings for Blacks.

Stribling was one of the most influential of the original 13 APA members, and the members apparently charged ahead with segregation policies. Stribling developed a set of requirements for institutions to serve Black patients that conveniently resulted in their need to be treated in Galt’s asylum in Williamsburg. Stribling saw no contradiction in adamantly refusing to allow a Black patient into his hospital while permitting enslaved Blacks to move freely about his hospital to serve well-to-do white patients.

In volume 2 of the American Journal of Insanity (now the American Journal of Psychiatry [AJP]), the editor, Amariah Brigham, provided overviews of each asylum, drawing from materials produced by their superintendents. He poked at Stribling, commenting, “We notice that colored persons are not received as patients into the Western Asylum” (Stribling’s hospital) and then quoted extensively from Stribling’s hospital report. Stribling went on at great length as to why the asylum needed to own slaves. As to the question of why he did not admit Black patients, he said, “We have never found it practicable [sic] to admit them.” No member of the Association asked for an explanation of this meaningless reason. No one challenged Stribling’s racism.

Stribling went further, arguing that services for “colored persons” are needed, but, he said, “for many reasons it would be desirable that an institution for colored persons should be entirely distinct from those occupied by insane whites.” No one in the Association asked Stribling what those many reasons were. Stribling went on to say this was not his problem—it was a matter for the legislature to deal with. As we shall see, 25 years later and four years before Stribling’s death, Virginia opened the first all-Black psychiatric hospital in the nation.

Woodward had his own struggles with how to deal with Black patients. It was generally accepted that Black patients should not lodge with white patients, so Woodward constructed separate housing for Black patients. But this violated other principles of separation in which Woodward believed: Men and women should be housed separately. Patients should be separated by the stages of their diseases, such that convalescing calm patients, incurable patients, noisy and violent patients, and curable patients should all be housed separately. It is not clear whether Black and white patients mixed during the day, but with regard to another hospital population—male and female patients—they were housed separately, yet Woodward wanted them to mix as much as possible during the day.

Housing Black patients separately, in much poorer circumstances than white patients, was the temporary solution adopted in Southern states at a time when states had only one public psychiatric hospital. In these asylums, Black patients and white patients never mixed. The outlier was the Williamsburg, Va., hospital (Galt’s hospital). It had 100 patients when APA was formed, 15 of whom were Black and were not segregated from the white patients. It’s clear that there was no consensus on integrated or segregated asylums among the 13 superintendents. What does appear to have been tacitly agreed upon is that there would be no confrontations on the subject, at least not officially, as reflected in the Association’s minutes.

Psychiatrists found themselves in the position of having to address the issue of integrated or segregated facilities much sooner than not only the rest of medicine, but also most establishments of work and recreation. In most places in the 1840s, integration was de facto. By not objecting to Stribling’s proposal, the Association was on record as condoning segregated facilities.

Not only did some of the first cohort of white Southern psychiatrists refuse to admit Black patients to their hospitals, but they influenced those who followed to create more segregated facilities than they were originally inclined to do. Stribling influenced Charles Nichols in the design of the Government Hospital for the Insane in Washington, D.C., to house Black patients in separate buildings behind and at some distance from the better facilities for the white patients. Nichols was required to care for Black and white patients as his was the only asylum in the District, so housing them in separate buildings was, from Stribling’s point of view, the “best” he could do. Psychiatric hospitals in the first half of the 19th century have the shameful distinction of being some of America’s first officially segregated institutions.

The 1850s-1860s

Only a few years later, in 1851, two “diseases” that must be the absolute nadir of psychiatric diagnoses were promulgated by Samuel A. Cartwright, a native Virginian who practiced medicine in Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. He was not formally a psychiatrist, but he had spent part of his training apprenticed with Benjamin Rush. His two diagnoses were drapetomania—the disorder that purported to explain why slaves run away—and dysaesthesia aethiopica—a disorder that supposedly explained laziness and a lack of work ethic among Blacks. Cartwright believed runaway slaves had a disease because God created Blacks to be “submissive knee benders.” In other words, Blacks were genetically programmed to be slaves, and it was an aberration, a disease, if they did not want to be slaves. Cartwright believed that dysaesthesia aethiopica was predominantly found in free Blacks and affected nearly all of them. According to Cartwright, without a “master,” the Black person was lost.

Cartwright’s theories were embraced in the slave states and mocked in the free states, including in medical journals. APA was silent. So far I have not been able to find any articles in the official journal of APA (AJP) that addresses the assessment, diagnosis, or care and treatment of Black patients in the first three generations of the Association. APA held to its already established pattern of silence on matters related to race.

In 1852, the American Journal of Insanity printed an article by Edward Jarvis pointing out the fallacies of the 1840 census, material he had published years before in other journals. Apparently, having failed to influence the thinking of the Association, Jarvis tried again at the 1862 Annual Meeting. It’s worth remembering that Jarvis had no power in the Association as he was not a superintendent or a psychiatrist—so he could not be a member. He started his discussion on the subject of the “colored insane” by talking about his survey of the “insane” and the “Irish insane” in Massachusetts (a subject of only passing interest to any but the Massachusetts members). His remarks are recorded in the journal in the minutes of the Annual Meeting.

Jarvis referred to the “data” in the census as “a pure creation of the imagination.” He pointed out that many towns had a number of “colored insane” despite not having any colored persons listed in their census. He emphasized that this census “has done a tremendous amount of political and scientific mischief.” It took Jarvis over 20 years to get this information about the misleading 1840 census into the journal. This misinformation spread to England, France, and Germany. Jarvis highlighted an article by a Frenchman using a formula based on the “fact” that the rate of insanity in the “Negro” decreases the farther one goes North, suggesting that as one arrived at the North Pole, one would have more insane people there than there were people. Isaac Ray interrupted Jarvis and changed the subject.

Summary

In 1889, the American Journal of Insanity published an index for its first 45 volumes. While that goes beyond the time frame of this article, there is no heading for any topic that would have been related to mental illness in Black Americans in that period.

At the first meeting of the Association, the 13 attendees created 16 committees, one of which was the committee “On Asylums for colored persons.” Galt; Stripling; and William Maclay Awl, superintendent of the Lunatic Asylum of Ohio, were the committee members. At the second meeting, there is mention that Galt presented a paper on the “colored insane.” Nothing was said about the paper, which was never published in the journal. No other paper on the subject appears until beyond the Civil War. In year after year of reports by asylum superintendents about their institutions, only once, Nichols, the superintendent of the Government Hospital for the Insane, in 1857, reports on the number of white insane and the number of “colored insane.” No one had done that previously, and no one, including Nichols, did so after that.

Looking back, it appears that during APA’s first 40 years, the leadership and the members were guilty of magical thinking, denial, and downright deception with regard to Black people. AJP is filled with beautiful, majestic engravings of Kirkbride’s model for the asylum and its application throughout the United States. There is no engraving, and hardly a mention, of the separate buildings constructed for the “colored insane.” Such renderings were made, as some still exist, but they were never on the journals’ pages.

It is not possible that the 13 original members did not know about the controversies around free Blacks and enslaved Blacks. When APA was established, there were 13 free states and 13 slave states. When new states were admitted, there was an attempt to admit one free state and one slave state to keep the numbers equal. If the superintendents didn’t know about hospital segregation when they created APA, they all quickly learned that some of their colleagues refused to admit people of color to their asylum and insisted there be segregation by race. Also, during this time, Association members were not opposed to discussing the segregation of the insane population on the basis of certain traits, such as sex, and rejected the idea that their hospitals should be segregated by socioeconomic status. But Association members did not debate segregation by race. A few members said it shall be so, and the rest were silent—silent for a very long time. ■