Special Report: America’s First Asylum for African Americans Marks 150th Anniversary

Abstract

The history of Central State Hospital in Petersburg, Va., is tied to the history of American psychiatry and APA.

At APA’s 2019 Annual meeting in San Francisco, where the Association marked its 175th anniversary, thousands of members and guests were invited to celebrate APA’s historic origins in Philadelphia in 1844. An important feature of the celebration was a wall display of large photographs, including those of the first two public asylums opened in the United States in the 18th and 19th centuries.

As a former commissioner of the Virginia Behavioral Health System, I was pleased to see the pictorial displays and history of the first two state hospitals in Virginia (Eastern State and Western State) and their medical superintendents (Drs. John Galt and Francis Stribling, respectively, both co-founders of the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane, the forerunner of APA). However, the display made no mention of Central Lunatic Asylum for Colored Insane, which opened in 1870; it was the first state asylum in the nation created for newly freed slaves. It was renamed Central State Hospital in 1894.

Eastern, which opened in 1773, was the first public mental institution in the United States and admitted one free African American a year until the end of the Civil War. Western, which opened in 1825, remained racially segregated until 1967. The idea for such a hospital was proposed and sanctioned by an APA commission chaired by Galt; Stribling; and another co-founder of APA, William Awl of Ohio. It influenced the policy direction of public psychiatric hospitals throughout the nation for the next 100 years.

Although Central State’s obscurity in conferences, research, and literature in the 21st century is troubling, I propose its historiography is tangential to understanding current discussions and massive street demonstrations that seek to finally eliminate America’s long racist history, vestiges and symbols of white supremacy, and acceptance of continued discrimination. These forces constitute the most virulent social determinants of health, which cause and sustain racial inequality and disparities in individuals, communities, and state hospitals.

On June 7, when the Commonwealth of VirginSia commemorated the 150th anniversary of Central State Hospital, the world was in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and daily demonstrations to end police brutality and racial inequality and eradicate symbols of white supremacy. The pandemic has disproportionately affected African Americans, who have a host of preexisting social disparities that increase their risks. The resulting economic dislocations have also had a disproportionate impact on unemployment and business ownership in minority communities. The video-recorded deaths of Black individuals by police officers has led to massive demonstrations and questions about how to change the behavior of police in African American communities.

Central to each of these current events are unresolved issues of race, white supremacy, and overt disparities in the distribution of wealth and opportunity. This confluence of unanticipated conditions and events in 2020 has heightened the importance of the evolution of race in psychiatry generally and the 150-year journey of Central State Hospital to provide quality services to a racially oppressed population.

For close to 100 years after the opening of Central Lunatic Asylum, racially separate state institutions and practices proliferated throughout the South, while segregated wards and buildings were ubiquitous in the North. Stribling’s stance on segregated inpatient care was adopted as public policy throughout the Southern states and as de facto policy of APA. Segregated state hospitals were often underfunded, overcrowded, unrepaired, understaffed, and dependent on uncompensated patient labor often masqueraded as effective treatment. Much of the care they provided was substandard as shown in a review of treatment records.

The 1964 Civil Rights Act compelled racial integration in public mental health systems; however, recent studies showed that implicit bias has influenced the design and delivery of psychiatric assessment and treatment. The first federal publication that sought to shed light on such bias in mental health care was Surgeon General David Satcher’s 2001 report, “Mental Health: Culture, Race and Ethnicity.” The report identified numerous gaps in research, knowledge, practice, and policy. Since it was issued, several contemporary research studies documented the continuation of implicit bias and disparities in mental and physical health owing in part to a host of social determinants that are at the heart of current civil demonstrations. We lack solutions.

Quest for Freedom Pathologized

Patients engage in diversional occupation, which consists of leisure and recreational activities to promote mental and physical health. This photo appears in the 45th Annual Report of Central State Hospital.

Although Galt believed that integrated psychiatric treatment could take place if African Americans had a history of freedom, in 1845 Stribling successfully proposed to the Virginia legislature that a separate psychiatric facility had to be created for African Americans based on their differences from white individuals. Virginia legislators agreed that racial segregation of psychiatric patients and sterilization of Black patients were essential, ethical, medically acceptable, and politically expedient at the close of the Civil War. But in their debates, only minimal attention was given to how to assess and treat any long-term traumatic effects of enslavement and how to mitigate the overt racist behaviors and policies faced by African Americans as they sought to transition into a democratically free society in which the color of their skin was synonymous with pathology and danger. In 2009, psychiatrist Jonathan Metzl wrote that the effort to secure freedom and equality by African Americans was pathologized to rationalize the need for an inordinate rate of long-term institutionalization, involuntary admissions, sterilization, imprisonment, segregation, police surveillance, and control.

The opening of the Central Lunatic Asylum for Colored Insane in 1870 culminated a decades-long (1840-1870) series of military, legislative, and medical debates, negotiations, and data analysis that inflated the impact that freedom would have on increasing the rates of insanity, violence, and crime in the newly freed African American population. The 1840 census falsely reported that free African Americans in Northern states had a rate of insanity 10 times greater than that represented by the number of Black individuals in asylums in the Southern states. These biased findings failed to indicate that only Galt’s hospital at Williamsburg admitted free Blacks prior to the mid-1800s. The false prediction that rates of insanity would substantially increase if enslaved individuals were freed from bondage was counter to the belief that Black individuals were immune from the risk of insanity and other ills prior to 1840.

The directors of Virginia’s two 19th-century asylums raised concerns with medical directors from other states about the need for a national policy to respond to predictions based on the 1840 census that mental illness in African Americans would greatly increase. In 1844, Galt, Stribling, and Awl formed a committee to recommend a national policy on asylums for African Americans. Galt and Stribling strongly disagreed on whether to integrate their own state hospitals by race and servitude when the legislature gave them this opportunity. Galt stated that there was no medical reason that Blacks and whites could not be served in the same facility, but he demurred wheSn it came to admitting the enslaved. He believed the enslaved were situationally immune from these illnesses because they did not own or manage property or engage in civic affairs, the sources of stress.

Central State Hospital hosted numerous famous performers for patients’ entertainment, including Louis Armstrong (above in 1956), Lena Horne, and Ella Fitzgerald.

In 1845, Virginia passed laws enabling free and enslaved African Americans to gain admission to state asylums based on the discretion of the individual directors and the willingness of slave owners to pay for their care. However, Stribling argued persuasively for a policy of racial separation that exempted Western State Hospital. Both Galt and Stribling were influenced by the prevailing hypothesis derived from the census that freedom was inimical to the mental well-being of those with a history of enslavement.

At the end of the Civil War, Union Gen. E. R. S. Canby confiscated all Confederate and private hospitals in Virginia. He chose an annex at Howard’s Grove Hospital, a former Confederate hospital located just outside of Richmond, for the treatment of African Americans. From 1865 to 1870, the federal government leased Howard’s Grove Hospital and converted the annex into an all-purpose hospital for formerly enslaved African Americans weighed down with conditions of insanity, physical disease, dislocation, homelessness, old age, violence, alcoholism, criminal behavior, and poverty.

The Commonwealth of Virginia extended the lease agreement from 1870 to 1885 and made substantial improvements to the temporary structures at Howard’s Grove. Howard’s Grove was inadequate as a medical facility, however, lacking sanitation, potable water, cooking space, and safe accommodations for individuals with disabilities. However, questions of legal ownership of new structures built by the state at the termination of the lease forced the Virginia legislature to abandon Howard’s Grove as a permanent psychiatric hospital for African Americans.

Virginia Establishes Central Lunatic Asylum for Colored Insane

The legislature was responding to Canby’s binding order that the state could utilize Howard’s Grove only as a temporary psychiatric hospital, suggesting clearly that a permanent hospital was required. In his order, Canby wrote, “The use of public buildings at Howard Grove Hospital, until the Legislature shall otherwise provide, are turned over to the State of Virginia for the purpose of establishing a temporary lunatic asylum” for the “colored insane.”

Above is a view of a hospital ward at Central State Hospital. The hospital once housed as many as 12,000 patients at a time and more than 300 people in one room.

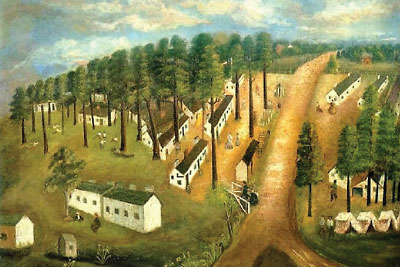

By June 1870, the Virginia legislature and Gov. Gilbert Walker passed legislation accepting responsibility for the newly created asylum exclusively for freedmen and formerly enslaved individuals. However, the inadequate annex was rented and used for the next 15 years. In 1882, the Virginia “Asylum Committee” proposed that a new facility would be constructed on the 584-acre Mayfield plantation in Dinwiddie County. The former plantation had been purchased by the Petersburg City Council for $15,000 and given to the commonwealth for development of a new mental hospital for African Americans. The facility—Central Lunatic Asylum for Colored Insane—opened in 1885.

The number of admissions swelled throughout the 1870s, exceeding the hospital’s capacity. These numbers were evident in the first annual report published in 1870. From 1865 to 1870, only 80 African American psychiatric patients were admitted to Central Lunatic Asylum, an average of 16 a year. However, the number of psychiatric patients admitted was considerably fewer than that of individuals with primary medical care, economic, and housing needs and fear of racial assaults and violence from whites.

By 1885, when the new asylum was completed, the census of Central Lunatic Asylum exceeded 373 psychiatric patients. A relatively small number of psychiatric patients were transferred from Eastern Lunatic Asylum, local jails, and a private hospital in Richmond. However, the census doubled in size almost every decade, reaching a total of 5,000 patients in 1950. From 1870 to 1968, the rate of hospitalization was twice that of the African American proportion of the state’s population.

The hospital was renamed Central State in 1894 and was racially integrated in 1967 in response to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. It is fully accredited.

Current Unrest Can Be Channeled to Work for End to Racism

The 150th anniversary of Central State Hospital is a stark reminder of how far we have come on issues of race and mental health care and how far we have yet to go. There is an extensive history of “diagnosing” and interpreting civil rights struggles through a psychiatric lens. The 1840 census was one of the earliest and most insidious when it linked the quest for freedom and equality as a cause of “lunacy.” This assumption gave rise to such perverse diagnoses as draeptomania, defined as the pathological intent to escape from enslavement. The 1840 census was basically a prescription for the maintenance of slavery and the continued denial of human rights.

These interpretations and predictions became the impetus for the Galt, Stribling, and Awl commission that sought to develop a guide for the profession and states for managing the surge in African Americans with mental disorders. Their guide was instrumental in the federal and state governmental decision to create Central Lunatic Asylum for Colored Insane, the nation’s first race-based mental hospital. The tendency to interpret civil rights efforts through a mental health lens has resulted in an increase in admission of African American men diagnosed with severe mental illness into the 20th century, according to Metzl.

APA has been intimately involved in determining the typology and quality of services available to African Americans in the United States since the mid-19th century. Its most prestigious psychiatric leaders have used their considerable influence and knowledge to convince state and local governments about policy directions and funding for mental health research, education, and effective treatments. Their hypotheses have ranged from consideration that African Americans had situational immunity prior to the end of slavery to predictions of exponential rates of illness born out of a purported inability to manage veiled freedom.

Nonetheless, only rarely has the field questioned the pathology of racism. Central Lunatic Asylum sprung from intense debates over racial integration and the ability to provide services across racial lines that were more politically than medically determined. In each era there has been a need for assertive leadership to identify how change could occur. That time is here again. At this point in the 21st century, the field of psychiatry must view the current national and international unrest as an opportunity to provide guidance to state and federal governments and the American population about issues of race and how to mitigate the deleterious effects of bias, racism, violence, discrimination, and harm that have marked the country since these issues arose in the 18th century. ■