APA Task Force to Create Model for ‘Getting to the Right Number of Beds’

Abstract

The initial model will likely be fairly basic, but it can evolve to incorporate greater complexity and can be refined to reflect the needs of the community where it is used.

A shortage of psychiatric beds in public and general community hospitals results in overburdened emergency departments and outpatient services; in the worst case, patients become homeless or enter the criminal justice system. The APA Presidential Task Force on Assessment of Psychiatric Bed Needs in the United States is working to create a model for determining the right number of beds for any community.

How many inpatient psychiatric beds does a community require to meet the needs of patients in that community with psychiatric illness?

The APA Presidential Task Force on Assessment of Psychiatric Bed Needs in the United States, created by APA President Jeffrey Geller, M.D., M.P.H., is charged with producing a model that communities can use to answer that question, taking into account as many variables as possible within the community that may inform the answer.

Geller and other APA leaders say the ability to accurately calibrate the number of inpatient hospital beds per community is key to determining other services in the continuum of care for people with mental illness and crucial to repairing America’s mental health system.

“Fundamental to extricating ourselves from the current [public mental health crisis] is getting to the right number of psychiatric beds,” Geller said in his address at the Opening Session of APA’s virtual Spring Highlights Meeting in April.

The task force, chaired by past APA President Anita Everett, M.D., comprises more than 30 APA leaders, other mental health professionals who are experts in health services and population health, and members of the APA administration. It is tasked with delivering a white paper by December that includes a workable model for determining hospital bed needs within a community that can be refined and updated over time.

The ambitious initiative is being carried out by five subgroups who are addressing the following components:

Historical and contemporary use of psychiatric beds.

How to define and accurately quantify “beds” in a community. Today there is a wide range of settings (state, general hospital, private psychiatric hospital, residential treatment facility) with psychiatric beds, as well as beds for defined populations (child and adolescent, patients with substance use and mental disorders, forensic patients).

Financing of hospital beds.

Describing the “ideal” for other components of the continuum of care that will affect and be affected by the number of hospital beds.

Variables within the population that may affect the number of beds.

A sixth subgroup will utilize the information from these groups to create a model that encompasses all of these variables. The modeling subgroup is chaired by statisticians Elizabeth La, Ph.D., associate director in the health economics group at RTI-Health Solutions, and Kristen Hassmiller Lich, Ph.D., an associate professor of health policy and management at the University of North Carolina School of Global Public Health. They will be assisted by Nitin Gogtay, M.D., APA director of research, and members of the APA administration.

In interviews with Psychiatric News, Geller and Everett said that a few international models exist for determining bed capacity, while states and communities in the United States have relied on various ad hoc methods of doing so.

But there exists no model for looking systematically at the entire continuum of care for varying levels of severity of psychiatric illness and the number of psychiatric beds needed within that continuum of care. This is why subgroups of the task force will be focused on identifying community resources that might mitigate the need for inpatient care, as well as on defining and quantifying the various kinds of beds offered in different settings and for different populations. (For further reporting on this aspect of the task force, see the next issue of Psychiatric News.)

Ideally, Geller said, acute inpatient care needs to be seen as part of a system of care; it is possible that there are communities in the United States that have too many beds. “If they exist, we would like to know about it,” Geller said.

But he insisted that for some number of individuals at any one time, the hospital is exactly where they should be. “We make a mistake when we have a perspective that we should avoid hospitalization at all costs or that a person should be treated in a less restrictive setting or one more integrated in the community simply because he or she can be,” he said. “Nowhere else in medicine has that perspective—if that were the case, the majority of neonatal deliveries would be home deliveries. It’s less restrictive, and we could do it. But we don’t because we err on the side of caution and best services for the patient. We should have the same perspective for patients with psychiatric illness.”

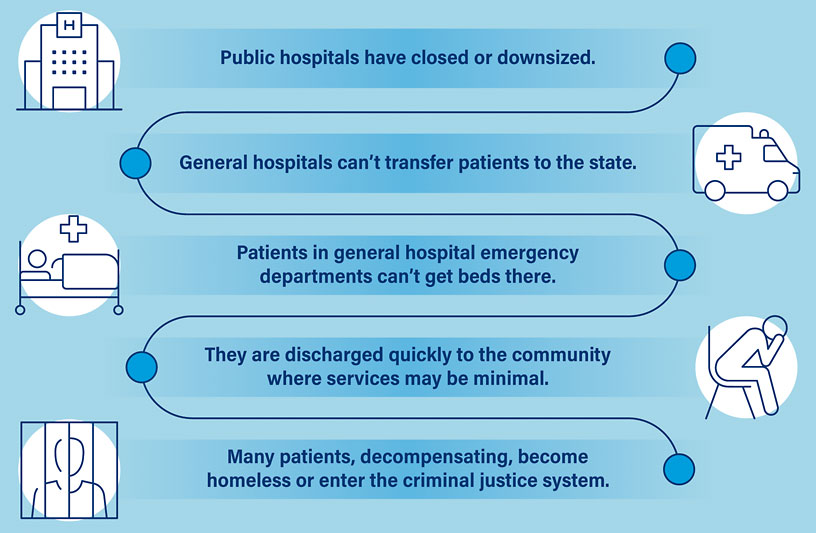

Domino Effect Leads to Homelessness and Incarceration

So, why is getting the right number of beds so important?

“If a public psychiatric hospital has a bed shortage, people who are in general hospital psychiatric beds can’t be transferred to the state hospital,” Geller said. “That means people in the emergency department [ED] of the general hospital can’t be transferred to a psychiatric inpatient bed in a general hospital. That leads to overcrowding of the ED with individuals being boarded—sometimes for days or weeks—while bed searches are going on. And most of those searches end up with, ‘We don’t have a vacancy.’ ”

He added that patients in general psychiatric hospitals are competing for the same beds as patients with serious mental illness in the forensic system. “Forensic patients are going to take precedence because the state has no choice but to treat them,” Geller said.

In turn, hospital EDs evaluate and discharge patients with greater speed than they might otherwise do so the ED doesn’t become inundated. “That puts a stress on outpatient settings dealing with patients who were never adequately stabilized.”

At the end of this chain is what might be regarded as the worst-case scenario, what past APA President Steven Sharfstein, M.D., called “the public health and clinical disaster of seriously mentally ill individuals who become homeless and incarcerated.” Sharfstein is a member of a task force subgroup, chaired by Mark Olfson, M.D., looking at the history of inpatient psychiatric care and how it has shaped services today (see box).

How We Got Here: Inpatient Care Falls Prey to Economic Forces, Ideology

Patients visiting the emergency department (ED) with psychiatric illness are “boarded”—forced to wait an average of 6.8 hours to 34 hours for an inpatient bed, according to research cited in a 2018 APA resource document titled “Boarding of Mentally Ill Patients in Emergency Departments.”

A study in the February JAMA Pediatrics reported that adolescents visiting the ED for psychiatric illness were boarded on average for 54 hours. Anecdotal reports of adults or children boarded for as much as a week or more are not unheard of.

How did this country reach such a crisis?

“Access to inpatient psychiatric beds undergirds local public mental health systems,” said Mark Olfson, M.D., M.P.H., a professor of psychiatry and epidemiology at Columbia University and chair of a subgroup looking at the history of inpatient psychiatric services as part of the work of the APA Presidential Task Force to Assess Psychiatric Bed Needs in the United States.

“It is essential that mental health systems help to stabilize adults or young people who are experiencing severe symptoms. Without this capability, it’s very difficult to have a well-functioning community public mental health system outside of the hospital. Unfortunately, there has been very little research on the effectiveness of inpatient psychiatric care. As a result, it has been vulnerable to regulation by managed care, ideological concerns, and other economic and political considerations that have narrowed the role of inpatient psychiatric care.

“An awareness of this history is important to understanding our current circumstances.”

Past APA President Steven Sharfstein, M.D., a member of the history subgroup, echoed Olfson, Geller, and others on the task force in emphasizing that the right number of beds for a community depends on the resources and services available in the community. The two service options can’t be viewed in a vacuum—or in opposition to each other.

“As a community psychiatrist by training, I believe ideally we should treat people close to home or close to where they work, and I believe the long-term custodial institutionalization of people was not a good chapter in psychiatry,” he said.

“But we need adequate access to beds. The recent history of care for psychiatric patients in America hasn’t been focused on their clinical needs; it’s been focused on what we are willing to pay for or it’s been driven by ideology—a belief that hospitals are bad.

“Hospitalization isn’t a failure—it’s a tool. A good Assertive Community Treatment team needs to have a back-up to reset a community treatment plan for people who are not taking their medication or are resistant to care.”

“Boarding of Mentally Ill Patients in Emergency Departments” is posted here.

“Characteristics of Mental Health Patients Boarding for Longer Than 24 Hours in a Pediatric Emergency Department“ is posted here.

Geller and Everett said that the initial model the task force produces in December to help communities reverse this trend will likely be fairly basic, if only because nothing else exists. “It can evolve to include more variables and more complexity and can be refined to meet the particular needs of a given community,” Geller said. “But our goal is to produce something that communities can start to use.”

Everett concurred. “If we get started with something, we can optimize the model over time.”

She underscored the importance of “getting to the right number of beds” as a starting point for improving the entire continuum of care. At the July virtual meeting of the Board of Trustees where she introduced the work of the task force, Everett said, “The holy grail of system design is understanding how many psychiatric beds in a given community would be necessary to serve the needs of that community.” ■

APA members interested in learning about the task force or contributing to it are urged to contact Laura Thompson in the APA Division of Research [email protected].