Dementia Rates May Be Dropping in Some Countries

Abstract

A combined analysis of seven large population studies across Europe and the United States finds that dementia incidence has dropped about 13% each decade since 1988.

As the world’s global population continues to age, there is growing concern about the potential increase in Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. A large study published in Neurology offers some good news, however. Between 1988 and 2015, the incidence of new dementia cases per year has been declining across Europe and the United States by about 13% each decade.

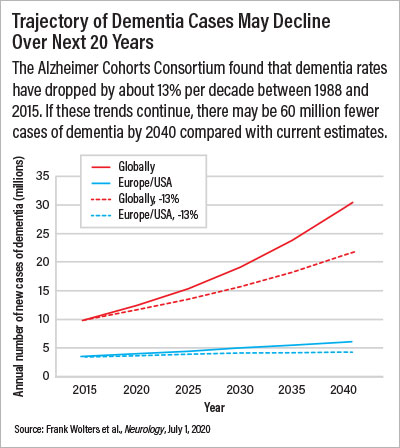

“If we assume continuation of this trend in Europe and North America into the coming decades, … it could imply that 15 million fewer people will develop dementia by 2040 in high-income countries,” wrote the study authors. If similar trends could be achieved worldwide, it would mean approximately 60 million fewer new cases of dementia by 2040, they added.

Previous studies in Europe and the United States have suggested that dementia is declining in Western countries. For example, one large study conducted by researchers at Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, suggested that dementia rates dropped about 25% between 1990-1995 and 2000-2005. “But you are always insecure when you find interesting data in just one group of people,” said Albert Hofman, M.D., Ph.D., who directed the Rotterdam study. He is the Stephen B. Kay Family Professor of Public Health and Clinical Epidemiology at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health.

To examine whether other populations were experiencing similar dementia trends, Hofman and several colleagues formed the Alzheimer’s Cohorts Consortium. This multinational effort includes seven large dementia studies—two in France and one each from the United States, United Kingdom, Iceland, Sweden, and the Netherlands.

The final sample spans the years 1988-2015 and included 49,202 participants who were at least age 65 at enrollment. All these participants were prospectively followed for at least two years and up to 27 years. Each of these studies defined dementia based on the DSM criteria (third or fourth edition depending on timeframe), which allowed the data to be seamlessly integrated.

A total of 4,253 new cases of dementia were diagnosed in the consortium sample. As expected, the rate of dementia increased with age. Dementia rates among different age groups were similar in men and women across the countries studied. (Hofman noted that many observational studies show that more women than men have dementia, but that can be attributed to women living longer than men on average.)

When exploring rates of all dementia over time, the study investigators found a continual decline since 1988, averaging at a 13% drop every 10 years. When focusing solely on participants who received a diagnosis of likely Alzheimer’s, the investigators found a 16% drop in new cases per decade.

There was a noticeable difference in the drop in the rates of dementia between the sexes: Dementia rates dropped about 24% per decade for men and 8% per decade for women.

Hofman told Psychiatric News that he and his colleagues from the Alzheimer’s Cohorts Consortium will dive deeper into their data to try and unravel which factors have been driving these positive changes. There are many contenders; since the mid-1980s there have been new therapies to help lower blood pressure and cholesterol, reductions in smoking rates, and more awareness of how healthy lifestyles in middle age can reduce dementia risk.

“This decrease [in rates of dementia] in high-income countries is very encouraging, but it could be reversed in coming years if trends toward [greater] obesity, diabetes, and lack of physical activity are not addressed,” said Helen Kales, M.D., the Joe Tupin Endowed Professor and chair of psychiatry at the University of California, Davis.

“There is also concern for the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cognitive and mental health of older adults,” Kales added. She noted how efforts to contain the spread of the virus have limited services on which older adults depend, including respite care and senior centers.

Kales, who was not involved in the consortium study, is also a member of the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care. The commission put out a report this past July suggesting that 12 modifiable risk factors account for about 40% of global dementia, suggesting an opportunity to drop global rates even further. These factors include obesity, diabetes, and physical inactivity as well as less education, hypertension, hearing impairment, smoking, excess alcohol consumption, traumatic brain injury, air pollution, depression, and low social contact.

Understanding which preventive strategies have the most impact is needed to deliver optimal preventive strategies to low- and middle- income nations that are currently experiencing their own uptick in population growth, Hofman said. He noted that reports suggest stable or rising rates of dementia over the past decade in Africa and Latin America.

“It is essential to achieve equal reductions in areas of the world where projected increases in dementia burden are steep and improvements in incidence thus far absent,” the authors wrote.

This study was funded by the Janssen Prevention Center in Leiden, the Netherlands. One study author was a previous employee of Janssen and others have received fees or research funding from the company; Hofman reported no competing interests in relation to this study. ■