Addressing Redlining, Community Cohesion May Improve Mental Health

Abstract

Community development professionals are increasingly understanding how their work is inextricably tied to addressing systemic disinvestment in communities and, ultimately, mental health.

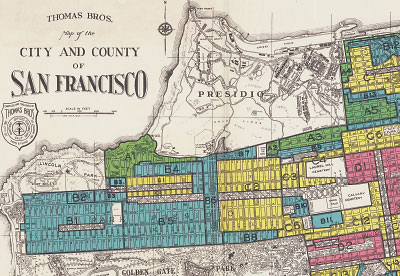

Redlining, as illustrated in this historic map of San Francisco, was instituted in the 1930s and involves labeling certain communities, particularly minority communities, as high risk for mortgage loans based on race and not ability to pay.

The maps of San Francisco are color coded with various shades of red and yellow. They represent vastly different measurements, such as which ZIP codes, as of 2016, were the most impoverished; where the greatest prevalence of people with poor mental health are located; and which neighborhoods were redlined in the 1930s because they were considered unacceptable for a mortgage largely on the basis of the racial composition of neighborhoods.

Yet when the maps are placed side by side, they look almost identical, with the darker shades representing the worst poverty and mental health (measured as adult residents reporting poor mental health for more than 14 days) largely lining up with those neighborhoods that were redlined.

Laura Choi, vice president of community development and community affairs officer with the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, wrote an article in 2019 in which she explained each of the maps. She drew the link between historic redlining, poverty, and poor mental health, as measured by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 500 Cities Project.

“Although the causal pathways are complex and multifactorial, it is clear that neighborhood-level factors, and therefore community development interventions, do indeed matter for mental health,” Choi wrote.

Choi is among a growing group of people in the community development field who are increasingly focusing on what community vitalization can mean for residents’ mental health. In 2018, she was the co-editor of an edition of the Community Development Innovation Review, a publication of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, titled, “Mental Health and Community Development.”

“Most of us in the community development field knew very little about mental health, how to talk about it, or how we can work together with the mental health sector to advance mental health through community development,” Choi told Psychiatric News. “In addition to improved neighborhood conditions, communities need trauma-informed care and efforts that focus on social cohesion, trust, and creating a sense of belonging. All of that matters for people’s mental health, and I think the community development field is trying to figure out what that looks like.”

Mindy Fullilove, M.D., is a social psychiatrist and professor of urban policy and health at The New School who has written extensively about the intersections of community and public health. She leans heavily on the work of Alexander Leighton, M.D., who posited that what keeps people well in a community is social connectedness and the ability to use connections to solve problems such as those associated with raising young people, achieving aspirations, and meeting basic needs.

Yet many communities across the country have experienced systemic disinvestment, as Fullilove outlines in her book Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America and What We Can Do About It. Modern policies such as urban renewal and deindustrialization destroy social bonds and leave communities fractured, Fullilove said.

“In communities that don’t have social integration, you’ll see poor health, including mental health problems,” Fullilove told Psychiatric News. “Fractured communities are fractious, and you have a real shift in how people feel and how they behave and how they think as things become more and more fractured.”

Redlining as a Present-Day Paradigm

Redlining was instituted by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) starting in 1933. It was essentially a practice of outlining the areas in which minorities, especially Black people, lived as a warning to mortgage lenders.

The website Mapping Inequality, a project of the University of Richmond, makes publicly available scans of HOLC documents, which detail some of the reasoning behind shading some neighborhoods red. In many cities, the concentration of Black individuals, sometimes mixed with certain immigrant populations, was the only reason necessary for giving an area a poor rating. In San Francisco, one area document reads, “There is a decided concentration of undesirable racial elements.”

Redlining, Fullilove said, continues to be the dominant paradigm of how cities are currently managed, in that there is investment in new buildings in areas where people are predominantly considered White. The definition of White, however, is arbitrary and has changed over time to incorporate people of different ethnic backgrounds, she explained.

But redlining didn’t come out of nowhere. It was implemented on top of existing segregation with the passage of Jim Crow laws. “So we’ve had roughly 120 years of city policies that have fractured the cities, disinvested in the minority neighborhoods, and then displaced people repeatedly,” she said.

Such systemic fracturing of communities leads to trauma and, ultimately, poor health outcomes. In an August 2020 study published in the journal Environmental Justice, researchers investigated health inequities in neighborhoods that were redlined in nine U.S. cities. They found associations between the redlined neighborhoods and the prevalence of cancer, asthma, poor mental health, and people lacking health insurance.

Community Development’s Role in Improving Mental Health

Community development is an interdisciplinary field that focuses on improving economic and social conditions to expand opportunities for low-income people. “There’s a recognition within community development that the place in which you live has an outsized influence on your health and economic outcomes,” Choi said. “We often say that your ZIP code is more important than your genetic code.”

Generally, when community development efforts are connected to health, the focus is usually physical health, Choi said. Thus, the dedication of an issue of the Community Development Innovation Review to mental health was meant to highlight what role community development can play in improving mental health. Part of that effort means partnering with the mental health field.

“When we integrate these two fields, we start to see a lot of opportunity to focus on people and better connect them with services and opportunities,” Choi said. “The opportunity for community development is to try to dismantle, as much as possible, the root causes and the negative side effects of redlining, like the concentration of poverty, the social exclusion, and the systematic denial of access to economic mobility.”

One example Choi pointed to as a group that is working to improve mental health through community development is Prevention Institute. A national organization headquartered in Oakland, Calif., the Prevention Institute, focuses on community trauma and violence prevention, especially how disinvestment in communities, erosion of their physical infrastructure, lack of living wage jobs, and other factors all contribute to community violence and mental distress, explained Sheila Savannah, Prevention Institute’s managing director.

“Our environments are feeding us information all the time—about how safe we feel, how we experience hopefulness and aspirations, and even how we view our self-worth,” Savannah said. “Community development is uniquely positioned to do this type of transformative work. In partnership with local groups, we can go into a community that has experienced prolonged disinvestment and poor outcomes to envision with residents what their community could be in the future.”

One of the initiatives Prevention Institute works with, Communities of Care, involves coordination with 10 grantee collaboratives funded by the Hogg Foundation in the greater Houston area. Each grantee looks at social determinants of health to improve the mental health and well-being of children and youth of color and their families.

Savannah grew up in the South Side of Chicago, and she noted that seeing historic redlining maps matched what she experienced in the neighborhoods around her. “I could viscerally see how the investment differed in [differently] zoned areas across the city and changed what was possible for the residents who lived there,” she said. “When you start looking across the country at redlining maps, you realize that this was deliberate; it just began a long time ago. You also become aware that a lot of those patterns of investment are practices that are still in place now.”

The Role Psychiatrists Can Play

For Savannah, not only must the community development and mental health fields work together, they also must find opportunities to be combined. “Training professionals in different specialized disciplines has, in some ways, done us a disservice because we go through academic institutions and get separate degrees and start using different language for the same ideas,” she said. It makes collaborative work more difficult.

When psychiatrists get involved in community efforts, they can help reduce stigma, Savannah said. It can bridge the gaps people may see between themselves and psychiatry, she explained.

There are no magic bullets to address the systemic disenfranchisement of communities all across the country, Fullilove said. Part of the answer is awareness of the plethora of policies that undermine community connections and displace people. Yet if people are given even a modest amount of support to create the social connections they may be missing in their communities, they will rebuild, she said. “Rome was sacked by the barbarians, and now Rome is one of the most beautiful cities in the world,” she said. “People rebuild.”

While many psychiatrists are focused on mental illness and its treatment in clinical settings, many also try to consider how to treat the illnesses of society, Fullilove said, and this is where they can be proactive in correcting the policies that harm communities. During her public talks, Fullilove often makes the point that policies that hurt certain communities ultimately hurt everyone in a society.

“That’s really where psychologists and psychiatrists can play a huge role: in explaining to people, one individual at a time, how everything is interconnected,” she said. ■