Special Report—ADHD: A Complex Disorder of the Brain’s Self-Management System

Abstract

Assessment of ADHD requires collection of information about how the patient functions in a wide variety of complex daily tasks at different times of day in different settings relative to other individuals of similar age.

The disorder currently known as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has long been seen as simply a behavioral problem of young boys who are excessively restless and inattentive. Among much of the public and even among many medical and psychological professionals, it is often misunderstood. However, ADHD is gradually being recognized as a complex neurodevelopmental disorder of the brain’s self-management system, its executive functions.

This syndrome affects not only young boys, but also young girls. It is no longer seen as a set of problems that remit in adolescence. Research by Barkley, Murphy, and Fischer (2008) has demonstrated that for 70% of those with ADHD, impairments persist into adolescence and often also into adulthood, impacting not only schooling, but also employment and social interactions.

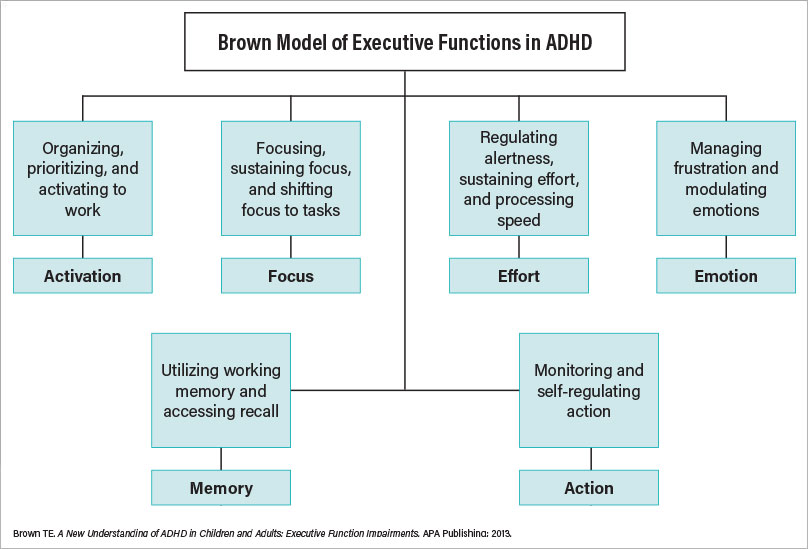

I have proposed a model showing six executive functions impaired by ADHD: activation, focus, effort, emotion, memory, and action (see illustration). Here are some important points about this model:

Demands on executive functions increase with age as the child’s abilities increase. A 4-year-old is expected to be able to get dressed without constant parental assistance but is not expected to cross a busy street unassisted. Most 12-year-olds are expected to be able to ride a bicycle but not safely drive a car.

Everyone has difficulty with these executive functions sometimes. It is not unusual, even for adults, to lose focus occasionally while listening in a meeting or reading a book or to forget what they were about to do. For those with ADHD, these functions are more often and more severely impaired than for most others of similar age.

Executive functions operate very quickly, usually with automaticity and without much conscious thinking, except for unfamiliar situations recognized as requiring a slower, more thoughtful approach.

Although ADHD was once seen as always involving hyperactivity and impulsivity, many with ADHD have never been hyperactive or impulsive. Some tend to be somewhat sluggish.

ADHD has nothing to do with a person’s intelligence. Some extremely bright and accomplished people suffer from ADHD despite a high IQ. Studies have shown that ADHD is found in people across the full range of intellectual abilities.

Executive function impairments of ADHD are a very heritable syndrome. Among those diagnosed with ADHD, about 1 in 4 has a parent with ADHD. The remaining three usually have at least one other blood relative with ADHD, for example, a sibling, grandparent, uncle, aunt, or cousin. ADHD syndrome runs in families.

The Central Mystery of ADHD: Executive Functions of ADHD Are ‘Situationally Variable’

All people with ADHD tend to have a few tasks or activities that strongly interest them and for which they do not experience executive function impairments. Because affected individuals can focus very well for a few specific tasks that interest them, it is often assumed that ADHD is simply a lack of willpower. People may say, “If you can do it here, you certainly should be able to do it for other tasks you recognize as important.” Strong interest or strong fear about a task changes the chemistry of the brain instantly and mobilizes attention, but these changes are not generally under voluntary control.

One of my patients compared ADHD to “erectile dysfunction of the mind.” He said, “If the task you are faced with is something that turns you on, something really interesting to you, you’re ‘up for it’ and you can perform. But if the task is not something intrinsically interesting to you, if it doesn’t turn you on, you can’t get up for it and you can’t perform. It doesn’t matter how much you tell yourself ‘I need to! I ought to!’ because it’s just not a willpower kind of thing.”

Assessment and Diagnosis of Executive Function Impairments

It was once assumed that a full neuropsychological evaluation involving “tests of executive functioning” was needed to adequately assess for ADHD. Such exams can be helpful for assessing physical damage from a brain injury or a stroke, but they are not usually helpful for diagnosing ADHD. There is no single test that provides an adequate assessment for the presence or absence of ADHD.

No EEG, no computer test, no neuropsychological test battery can capture the variety and complexity of functions involved in getting up in the morning and preparing to leave for school or work, riding a bike or driving a car in traffic, reading and comprehending papers or books, participating in social conversations, prioritizing a variety of tasks, and getting started on what is most important while avoiding distractions, yet shifting focus when needed.

Assessment of ADHD requires collection of information about how the patient functions in a wide variety of complex daily tasks at different times of day in different settings relative to most others of similar age.

The most effective way to determine whether a person may have ADHD is a well-conducted clinical interview with the patient by a clinician familiar with ADHD and, if possible, someone else who knows the patient well. Detailed directions for such an interview are included in my book Outside the Box: Rethinking ADD/ADHD in Children and Adults.

Initial evaluations should also include use of an age-normed rating scale for ADHD such as the Barkley Rating Scales, the Brown Executive Function/Attention Rating Scales, or the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF).

These normed rating scales are helpful in compensating for the fact that DSM-5 diagnostic criteria pick up some impairments of ADHD but do not include aspects of executive function impairments that are significant and occur commonly in many teens and adults.

Effective Treatment for ADHD in Children, Teens, and Adults

The most effective treatments for ADHD are carefully adjusted FDA-approved medications. For 8 of 10 persons with ADHD, stimulant medications significantly improve their impairments of executive functioning if the medication choice and dosing are carefully fine-tuned to adjust to that individual’s body. However, these medications do not cure ADHD as an antibiotic may cure an infection. When effective, stimulant medications simply alleviate the symptoms of ADHD during the time the medication is active, in the same way that eyeglasses or contact lenses may improve vision while they are being worn.

The effect of medication is variable—some patients benefit enormously, while others experience more modest improvement. For about 2 of 10 patients, a given medication may cause unacceptable side effects or not be helpful at all.

Fine-tuning of stimulant medications for each individual patient is essential. The most effective dose of stimulant medication for patients with ADHD is not usually tied to the patient’s height, weight, or symptom severity. Rather, the most important factor is how sensitive the individual’s body chemistry is to the specific medication being taken.

Most very young children respond best to relatively small doses, but for some, it is necessary to titrate to a much higher dose. Similarly, most adults respond best to fairly high doses, but there are a few, including some who are quite tall and heavy, who will do best on a dose not much stronger than is used for most young children.

Fine-tuning of stimulants does not refer only to the size of the dose; it also is related to the timing of dosage in relation to the patient’s daily activities. For example, many adolescents find that a morning dose of a long-acting stimulant like lisdexamfetamine dimesylate (Vyvanse), methylphenidate extended release (Concerta), or XR doses of other stimulants work very well for most of their school day. However, for many adolescents, these longer-acting medications taken in the early morning wear off at lunch or shortly thereafter, leaving no coverage for their afternoon classes.

Many who take longer-acting stimulant medications need a “booster dose” of an immediate release, shorter-acting version of that same medication to cover them for their afternoon classes. Some also need a “booster dose” in late afternoon to provide coverage for homework or other evening activities. There are significant differences in the rate at which even patients of similar age and size metabolize stimulant medications.

“Rebound” is another factor related to fine-tuning stimulant medications. This refers to the situation in which a given stimulant works without adverse effects during most of the time it is active, but then wears off too quickly causing the patient to experience restlessness, irritability, or blunting of emotion and the sensation of a “crash” that may last a couple of hours. Usually, such rebound reactions can be alleviated by adding a small dose of the short-acting formulation of that medication about 30 minutes before the crash tends to occur.

Medication Options Other Than Stimulants

In addition to stimulants, the FDA has approved several other nonstimulant medications as effective for treatment of ADHD. More than 30 studies have demonstrated the usefulness of atomoxetine (brand name Strattera) not only for ADHD, but also for ADHD accompanied by anxiety, tics, and some other comorbid problems. Unlike the stimulants, atomoxetine is dosed according to the patient’s weight.

Other nonstimulant medications approved for treatment of ADHD include guanfacine (Intuniv) and clonidine (Kapvay). Both are α2-adrenergic agonists that act primarily on the norepinephrine system and have been used to reduce excessively high blood pressure in adults. They may be helpful for ADHD in combination with stimulants to reduce excessive restlessness, irritability, aggression, difficulty in falling asleep, and/or tics (vocal and/or motor). More detailed information about adjusting dosing for these medications appears in my 2017 book.

Nonmedication Interventions for ADHD

Education of Patient and Family

It is important for clinicians to provide accurate and understandable information about ADHD to patients and their families. There is a lot of misinformation about this disorder that may discourage them from utilizing effective appropriate treatment. Before information is provided, it is usually helpful to ask the patient and family members what they already know about ADHD and what questions they may have about the disorder, its course, and its treatment. This may reveal myths or misunderstandings that could undermine compliance with recommendations.

Guidance for parents of children with ADHD often involves addressing concerns such as the following:

How can we resolve differences between us as parents about not only medication, but also how to deal with our child’s behavior in ways that are not too harsh and not too lenient?

How can we prevent ADHD from becoming an excuse for laziness or unacceptable behavior?

What should we tell the school? Should we ask teachers to make changes in how they deal with our child?

Are our child’s symptoms of ADHD likely to get better or worse as time goes on? What does this mean for his or her future education, relationships, and career?

Know the Laws Regarding Accommodations

For children or adults with ADHD, there may or may not be a need for accommodations in school or in employment. There are two levels of federal laws that provide for individuals with disabilities, including ADHD, who may need accommodations or supports not provided to other students or employees. Those laws include Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Individuals With Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, which was strengthened in 2006. Another applicable law is the Americans With Disabilities Act.

Examples of accommodations include the following:

Extended time for completing timed tests or examinations.

Reduction in the amount of written work required or extended time for completion.

More frequent reports from school to home, possibly including daily report forms.

Alternative seating of the student in the classroom.

A peer notetaker for lecture classes to supplement notes taken by the student (for example, in college classes).

Details about regulations for accommodations and how to arrange for appropriate accommodations are also included in my 2017 book.

Other nonmedication treatments for ADHD may include supportive psychotherapy, couples therapy, or coaching by a trained ADHD coach.

Comorbidity in ADHD

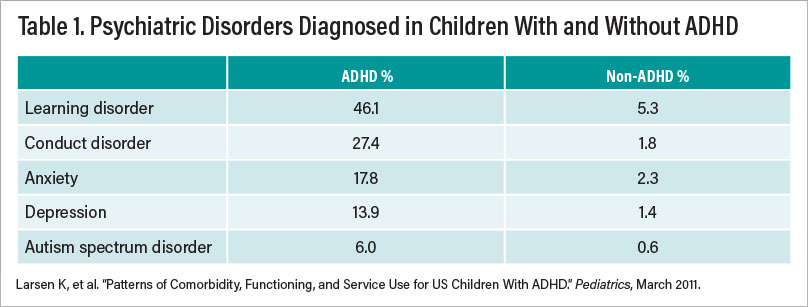

In children and adults, ADHD is often comorbid with other disorders. One large study involving 61,000 children aged 6 to 17 years found that those children diagnosed with ADHD had much higher rates of other disorders than those who did not have ADHD. Among those children with ADHD, 33% had at least one additional psychiatric or learning disorder, 16% had 2, and 18% had 3 or more (see Table 1).

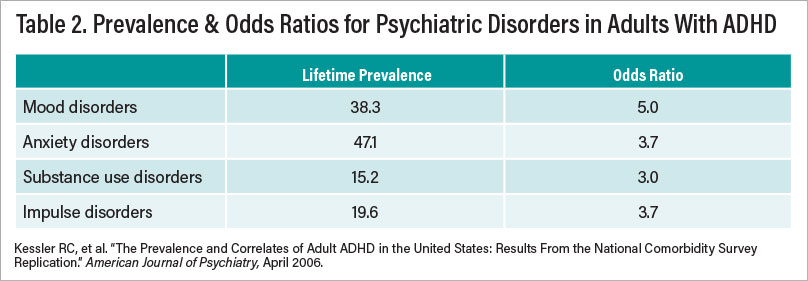

Co-occurring disorders are also very common among adults with ADHD. A nationally representative study of adults with ADHD aged 18 to 44 years who were not referred for treatment found that those with ADHD were 6.2 times more likely to have at least one additional psychiatric disorder at some point in their life than adults without ADHD (see Table 2).

In evaluations of children and adults with ADHD, it is not uncommon to have their comorbid disorder recognized and treated while their ADHD is overlooked or to have their ADHD diagnosed while a concurrent disorder is not recognized and treated. Detailed suggestions for adapting treatment for ADHD with various comorbid disorders are included in my 2017 book. ■

Additional Resources

Barkley RA, Murphy KR, Fischer M. ADHD in Adults: What the Science Says. New York: Guilford Press; 2018.

Barkley RA, ed. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment, Fourth Edition. New York: Guilford Press; 2015.

Brown TE. Attention Deficit Disorder: The Unfocused Mind in Children and Adults. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2006.

Brown, TE. ADHD Comorbidities: Handbook for ADHD Complications in Children and Adults. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2009.

Brown, TE. A New Understanding of ADHD in Children and Adults: Executive Function Impairments. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 2013.

Brown TE. Smart but Stuck: Emotions in Teens and Adults With ADHD. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Wiley; 2014.

Brown TE. Outside the Box: Rethinking ADD/ADHD in Children and Adults: A Practical Guide. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2017.

Brown TE. ADHD and Asperger Syndrome in Smart Kids and Adults: Twelve Stories of Struggle, Support, and Treatment. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 2021.