Why We Must Address Poverty

Poverty is one of the most destructive social determinants of mental health. Global forces such as the current pandemic, structural racism, climate change, and wars are contributing to a sense of future economic uncertainty. At the macro level, communities depend on government and public health measures to promote safety and well-being by providing financial resources.

A few weeks ago, I spoke with Benard Dreyer, M.D., a past president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, about poverty. He has spent years as director of the NYU Division of Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics researching and reporting on the lifelong effects of child poverty. As recently as 2019, the National Center for Education Statistics reported that 16% of children under age 18 were in families living in poverty. Dreyer and his colleagues have demonstrated that poverty strongly reinforces adverse childhood experiences and how the cumulative toxic stress of adversity can change the developing brain of a child. Dr. Dreyer would like to see the payments to families provided by the American Rescue and Families Plans Act of 2021 become part of the U.S. budget for at least five years to prove the beneficial effects of income support plans. On September 14, representatives of the Group of Six—APA, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Osteopathic Association, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American College of Physicians—engaged in discussions on Capitol Hill to provide our expertise on improving health and mental health.

Basic income programs have been around for a long time. Social Security became U.S. law in 1935 to pay retired workers and improve the general welfare of the public. In 1978, an experimental basic income program was introduced in Dauphin, Manitoba. It provided financial support that was marginally above the assistance rate to families. Mincome, as the government program was named, paid a stipend that over time was reduced as other sources of income increased. Mincome was remarkably successful. As poverty rates fell, physical and mental health improved, family violence and crime decreased, and the number of high school completions climbed. Participants reported less daily stress, and new mothers chose to use some of the stipend to take a longer maternity leave. Basic income experiments for families worldwide over the past four decades such as the one in Winnipeg have demonstrated similar positive results. Mitigating social determinants such as poverty were shown to ultimately reduce mental disorders (see "The need for a federal Basic Income feature within any coherent post-COVID-19 economic recovery plan").

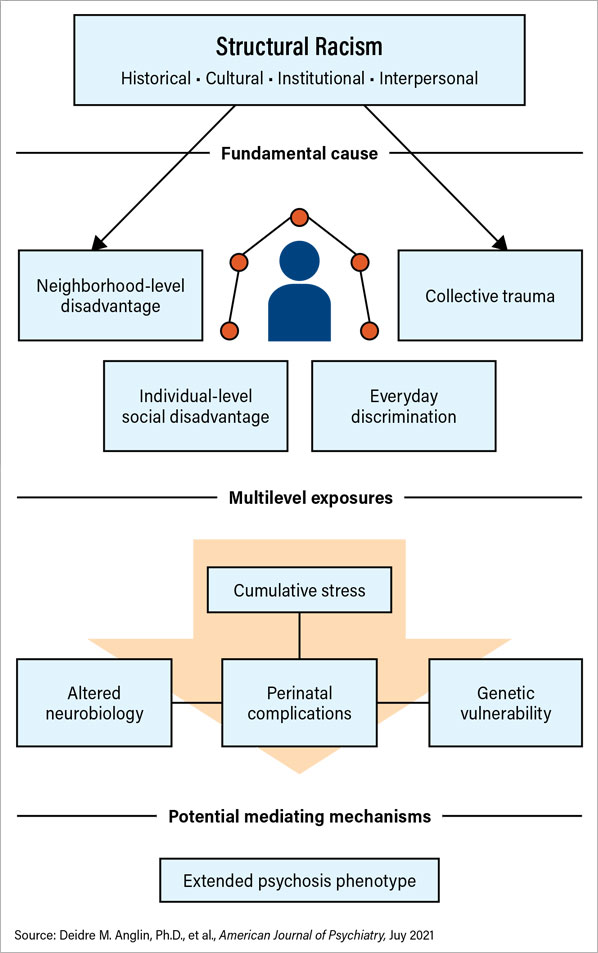

Compounding the effect of poverty is racism. The July issue of our own American Journal of Psychiatry contains several articles on the impact of structural racism on socioeconomic deprivation in communities. “From Womb to Neighborhood: A Racial Analysis of Social Determinants of Psychosis in the United States” by Anglin et al. elaborates a common (preventable) pathway to the diagnosis of psychosis in poor, minority, and immigrant populations (see infographic).

To take it a step further, socioeconomic disparity has been shown to have a pronounced effect on maternal health. The Momnibus Act (HR 959), co-sponsored by U.S. Rep. Lauren Underwood (D-Ill.) and supported by APA, addresses racial inequity. The Black Maternal Health Act of 2021 is motivated by the high mortality rate among Black mothers—three to four times higher than that of White mothers. Hispanic and racially minoritized mothers have similar high rates of maternal mortality. HR 959 proposes critical financial investments in social determinants of health to community-based organizations, including incarcerated moms. It also highlights mothers with perinatal mental health conditions and substance use disorder. Most importantly, the Momnibus Act seeks culturally informed solutions.

Basic economic support for families could be construed as analogous to vaccination in the mitigation of poverty and its effects on mental health. Psychiatry’s role has generally been one of late intervention, rather than early preventative measures. Shifting the focus in this way may amplify the effect that psychiatry can have on the prevalence of mental illness.

Just as vaccines are public health prevention methods, basic income programs, similar to other public health initiatives, have proven to mitigate social determinants by improving well-being, education, the environment, health, and ultimately mental health. Prevention and early intervention are the keys to decrease the rising need for an increased workforce.

Psychiatrists have a key role in promoting and advocating for mental health equity in clinical care, research, education, administration, and advocacy. Every psychiatrist and patient are part of one or several families, groups, cultures, races, religions, and communities. These connections are even more important in the context of isolation brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. Perhaps by witnessing the devastation wrought by the pandemic, climate change, genocides, and discrimination, the public is becoming more aware of basic human needs. Amid the current multiple crises, psychiatry must realign itself with public health initiatives that focus on the economic needs of generations of children. The current U.S. government plan is projected to cut child poverty in half in one year; that may be aspirational, but if we all work together, it can happen The outcome is a better future for all. ■