Special Report: Management of Major Depression—Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

Abstract

There are a large number of evidence-based treatments for depression, but for now we are still relying on trial-and-error approaches. This article discusses available treatments and guides you through the decision-making process.

The pain is unrelenting, and what makes the condition intolerable is the foreknowledge that no remedy will come—not in a day, an hour, a month, or a minute. If there is mild relief, one knows that it is only temporary; more pain will follow. It is hopelessness even more than pain that crushes the soul. So the decision-making of daily life involves not as its normal affairs, shifting from one annoying situation to another less annoying—or from discomfort to relative comfort, or from boredom to activity—but moving from pain to pain. One does not abandon, even briefly, one’s bed of nails, but is attached to it wherever one goes.

—William Styron, Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness

Major depression is one of the most often encountered syndromes in psychiatric practices and, indeed, in general medicine. Lifetime prevalence rates in the United States of 11% to 13% in men and 21% in women confirm the ubiquitous nature of this disorder. It is truly a killer—both due to the high rate of suicide in the depressed population (suicide is still in the top 10 causes of death in the United States) and the marked increased vulnerability of depressed patients to severe medical comorbidities including cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes, and certain forms of cancer. Taken together, these findings surely account for the reduced life span of patients with depression.

All medical students and psychiatry residents are well versed in the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for major depression, and space constraints preclude repeating them here. However, it is worth noting that additional symptoms not contained in the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria may be helpful to consider including diurnal mood variation and unexplained crying spells. This author, however, believes that the pathognomonic symptom of major depression is anhedonia, in a similar way that pathological worry is the single most cardinal and important symptom of generalized anxiety disorder.

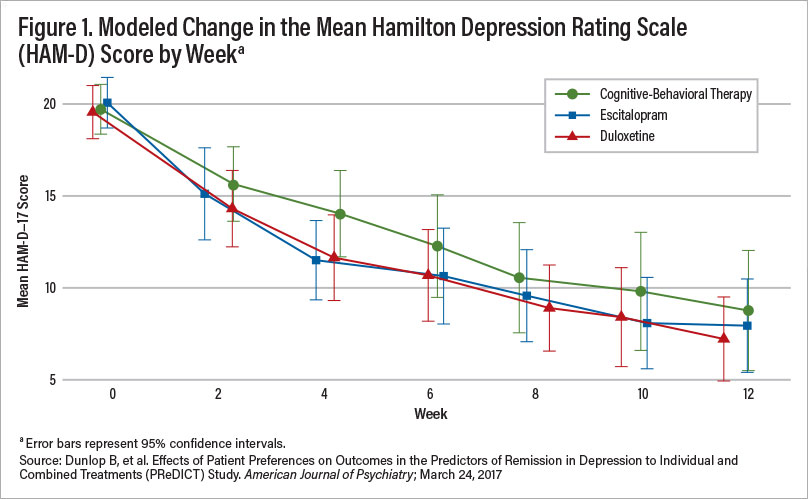

Figure 1

In terms of the diagnostic process as the necessary precursor to any discussion of treatment, three points are important. First, assessment for medical disorders or medications that are associated with depression such as hypothyroidism and glucocorticol treatment, respectively, to name a few, is essential. Occult hypothyroidism is the leading medical disorder associated with causing depression, and there is evidence that patients with a TSH > 3.5 IU/ml (not the 5.0 IU/ml cutoff described by most laboratories) already have incipient thyroid disease and do not respond well to antidepressants. Men with low levels of testosterone also frequently display the cardinal symptoms of depression and respond to testosterone supplementations, often not requiring antidepressant treatment. More importantly, there is evidence that men with low testosterone concentrations do not respond to antidepressant treatments.

Second, psychiatric comorbidity is more the rule than the exception in patients with major depression, and these comorbidities must be formally diagnosed and considered in the development of a treatment strategy. The most common include anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder) and posttraumatic stress disorder.

Third, delineating the subtypes of major depression is of great importance, as it too will impact optimal treatment decisions. The most pressing is, of course, major depression with psychotic features, which requires a treatment regimen completely distinct from that for nonpsychotic depression. Other subtypes of depression, more notably atypical depression, also suggest particular treatment algorithms.

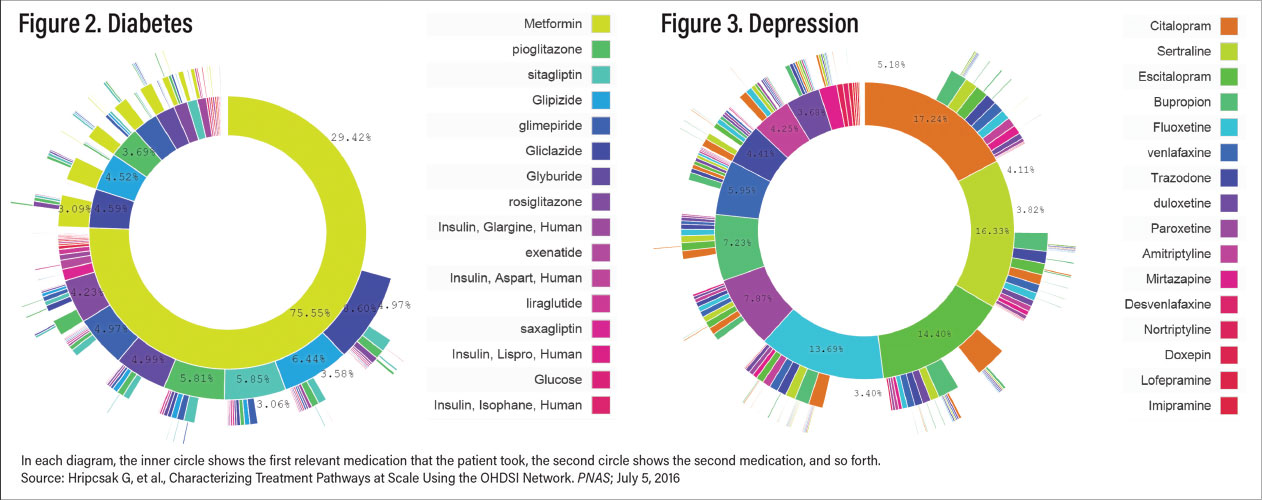

Figure 2-3

Space constraints preclude any discussion of pathophysiology of depression here, an area I reviewed in considerable detail in the August 2020 issue of the American Journal of Psychiatry. Suffice it to say that in spite of several decades of research, the underlying pathogenesis of major depression remains painfully obscure and, as such, does not guide treatment in any clinically useful way. This is perhaps best exemplified by the repeated failure of commercially available pharmacogenomic tests to predict response to one or another antidepressant in controlled trials despite claims to the contrary, a position now rigorously supported by the Food and Drug Administration.

It is important to note the consequences of inadequately treating major depression. It is now very well documented that persistent syndromal depression is associated with increasing treatment resistance, risk of suicide, risk of increased substance and alcohol abuse, vulnerability to several major medical disorders, and poor treatment outcomes. In view of these data, it is imperative to treat depression aggressively as you would any potentially lethal disorder.

Evidence-Based Treatment of Major Depression

Large-scale treatment studies ranging from the STAR*D study composed of a broad range of depressed patients to the PReDicT study of never-treated depressed patients revealed, using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), remission rates of 28% and 50%, respectively (see Figure 1). This suggests that a great many patients, perhaps the majority, do not respond to evidence-based monotherapy including antidepressants or psychotherapy. (STAR*D stands for Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression; PReDicT stands for Predicting Response to Depression Treatment.)

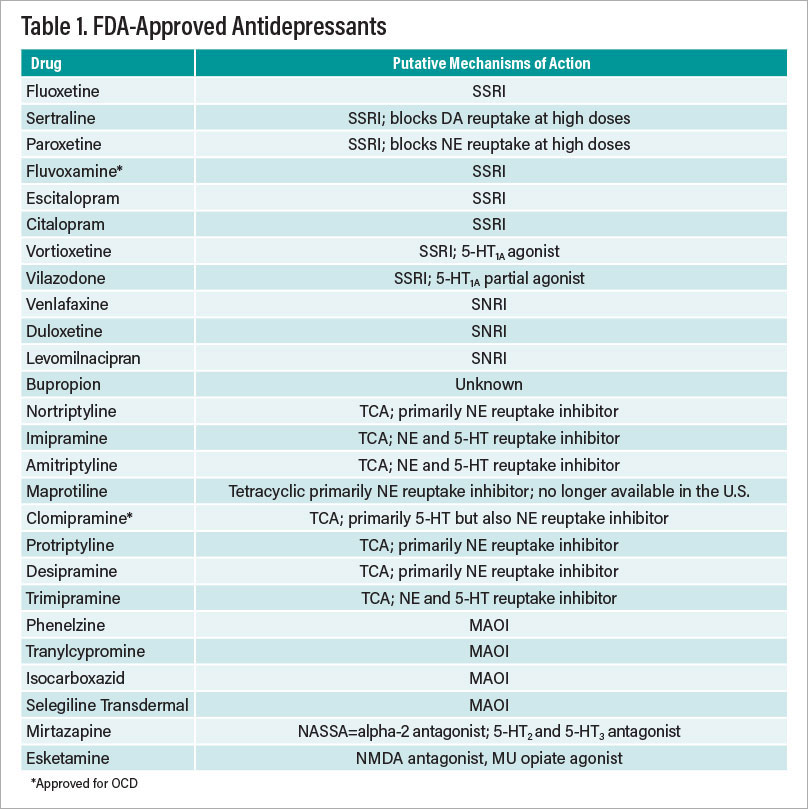

Table 1

Evidence-based treatments for major depression can be divided into several categories: Antidepressants, psychotherapies, and nonpharmacological somatic treatments. These last two include cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT), interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), and vagal nerve stimulation (VNS). The aforementioned antidepressants and neuromodulation modalities are FDA approved. In addition, there are a number of FDA-approved augmentation strategies—atypical antipsychotics that have been demonstrated in randomized, controlled trials to convert antidepressant nonresponders and partial responders to responders. There is also evidence that several non-FDA-approved treatments are also effective in this regard. Table 1 on the facing page summarizes the FDA-approved treatments of major depression.

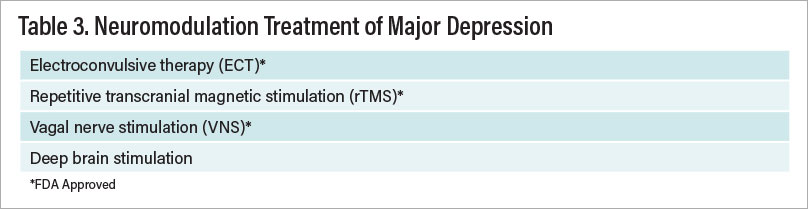

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the conundrum of treating depression compared with treating another common complex disorder, diabetes. Figure 2 reveals prescription data on the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Metformin is the clear first choice of treatment. Figure 3, in contrast, shows similar data for treatment of depression—there is no clear choice as there are no data indicating that any one antidepressant is superior in efficacy and/or has a most favorable side-effect profile. This leads to an almost purely trial-and-error approach to selection of treatment. In Table 2, the other treatment modalities are briefly discussed, followed by augmentation and combination therapies and finally novel approaches in various stages of development in Table 3.

What is a busy clinician to do?

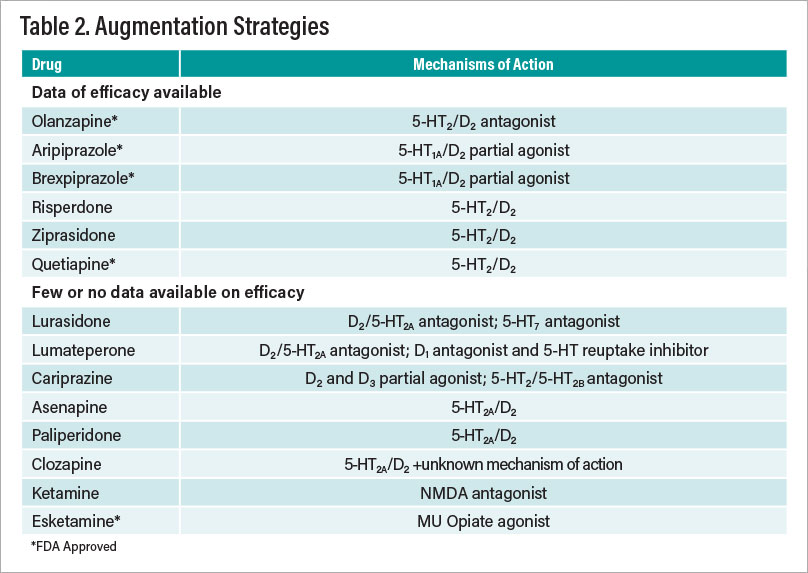

Table 2

Once a comprehensive diagnostic evaluation is completed and a diagnosis of major depression is established and underlying medical disorders have been ruled out, clinicians are faced with the first treatment decision. They should obtain a dimensional measure of depression severity such as the Beck Depression Inventory and obtain this assessment at each patient visit. This treatment decision is ideally made not solely by clinicians but by the clinician-patient dyad. Clinicians should present the menu of evidence-based treatments ranging from antidepressants to psychotherapy to neuromodulation. An important factor is family history—if a patient’s first-degree blood relative has suffered with depression and responded to a particular antidepressant, some evidence suggests that this agent should be a first choice for that patient.

As noted above, psychiatric comorbidities should also play an important role in decision-making, as should depression subtype. As an example, the place of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) in the treatment algorithm is higher in patients with atypical depression. Psychotic depression requires the use of not only an antidepressant but an atypical antipsychotic as well, unless ECT is chosen.

Factors to Consider Regarding Treatment Choice

With these exceptions, there is little to guide clinicians on treatment choice. Patient preference is clearly important and will drive much decision-making as to initial treatment direction, that is, antidepressants versus psychotherapy versus neuromodulation. As noted above, the available data from randomized trials do not support the use of commercially available pharmacogenomics testing to predict antidepressant response.

Table 3

In terms of antidepressant treatment strategy, clinicians should initially choose an antidepressant within a class with the most favorable side-effect profile and few, if any, drug-drug interactions. This, of course, eliminates tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and MAOIs as first-line agents, as well as older selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as paroxetine, fluoxetine, and fluvoxamine. Most clinicians would opt for escitalopram or citalopram although a case could be made for sertraline, fluoxetine (in children and adolescents), or vortioxetine. If there are major concerns about sexual dysfunction with SSRIs, buproprion is a reasonable first choice. Although a few studies that sought to determine whether beginning treatment with two antidepressants of different classes would result in a higher rate of treatment response had mixed results, what is clear is that the combination of two antidepressants at subtherapeutic doses is not effective.

Although no antidepressant can make the claim of being more effective than any other, there is evidence that the selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine has an advantage in remission rates over SSRIs as a group.

In general, the data suggest that patients who exhibit less than a 30% improvement after three weeks on antidepressant monotherapy are unlikely to respond to that dose. In the absence of side effects, the dose can certainly be increased, for example, sertraline from 50 mg to 100 mg. Moreover, in clinical practice, we have seen many patients who respond only to inordinately high doses of antidepressants, for example, sertraline 300 mg to 400 mg, venlafaxine XR 600 mg, and escitalopram 40 mg.

Suggested Next Steps if Failure Occurs

Once the antidepressant monotherapy trial is considered a treatment failure—the patient has not attained remission after an adequate trial of six to eight weeks at an adequate dose—the clinician and patient must make a crucial decision: to switch to another therapy (antidepressant, psychotherapy, or neuromodulation) or to maintain the current antidepressant and add a second agent (an antidepressant of another class or an augmentation agent such as an atypical antipsychotic, lithium, T3, or pramipexole). Again, if the initial antidepressant has not resulted in any substantial improvement in symptoms, the patient should be switched to another antidepressant of a different class, for example, from an SSRI to an SNRI, TCA, MAOI, or one of the atypical antidepressants (mirtazapine or bupropion). In contrast, if the patient has experienced considerable improvement, say 40% to 50%, then an augmentation or combination therapy should be initiated.

Similar to the dearth of information on predictors of response to individual antidepressants, there is little information to guide the clinician on next best steps. There is evidence for the addition of CBT to the antidepressant regiment, as well as TMS and a host of medication strategies, the latter summarized in Table 2. Space constraints preclude a comprehensive discussion other than to illustrate the few agents approved by the FDA to convert antidepressant nonresponders to responders. It is important to note that the magnitude of the beneficial effect of antipsychotic drug-induced augmentation is relatively meager. As an example, a study by Michael Thase, M.D., and colleagues in the September 2015 Journal of Clinical Psychiatry on the use of brexpiprazole as an adjunct to antidepressant treatments found that the groups treated with brexpiprazole attained only modest levels of remission compared with placebo. The good news is that there are many augmentation and combination strategies from which to choose, including lithium, tri-iodothyronine, and pramipexole, as well as combinations of antidepressants. Recently the literature on ketamine and esketamine was comprehensively reviewed by Roger McIntyre, M.D., and colleagues in an article posted March 17 in the American Journal of Psychiatry. Although much remains unknown about the long-term consequences of these drugs and clear abuse liability, it does ameliorate severe depression, even if transiently, in some patients.

Looking to the Future

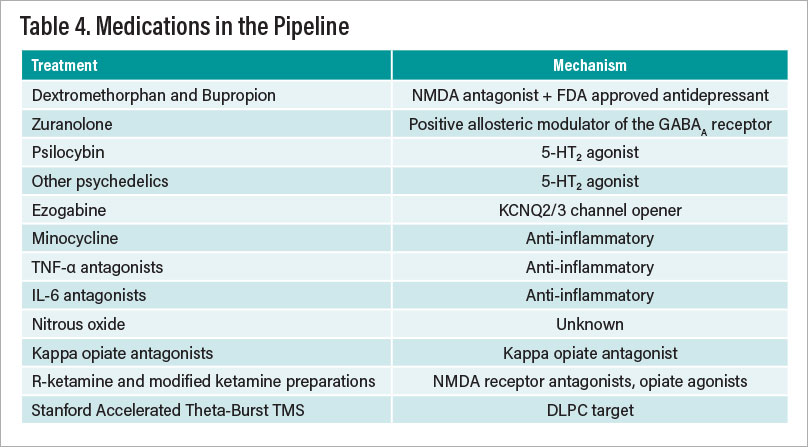

A remarkable resurgence in the development of new antidepressants is underway after a lull of several years. Table 4 on the facing page summarizes some of these new candidates that are in various stages of development.

Table 4

All of the treatments listed in Table 4 have at least one randomized, controlled clinical trial demonstrating efficacy in depression, mostly in treatment-resistant patients. Nonetheless, much additional work needs to be done before one or more of these treatments receive FDA approval. One obvious issue of great importance is the inability to “blind” treatment with some of these agents, most notably psychedelics and ketamine-related agents. The striking data from the Stanford group that the mu opiate antagonist naltrexone completely abolishes the antidepressant effects of IV ketamine suggest that the drug is acting as an antidepressant by either increasing endogenous opiates or acting as a mu opiate agonist. The difficult issue of the increasing placebo response in depression trials is a major obstacle in drug development and the use of electroencephalography (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) as well as machine-learning methods to predict placebo response would be a major advance.

Writing a few words about advances in neuromodulation strategies to treat depression is pertinent. In an open study posted in the American Journal of Psychiatry on April 7, 2020, Eleanor J. Cole, Ph.D., and colleagues reported that high-dose, accelerated theta burst TMS administered more precisely with a neuronavigator 5 minutes per hour for 10 hours on five consecutive days produced remarkably high remission rates in refractory depression, and there is now reportedly a completed sham-controlled, double-blind trial that confirms and extends these findings.

In summary, unlike the situation in the treatment of schizophrenia in which nonresponsive patients fundamentally have one treatment modality—clozapine, there are a large number of evidence-based treatments for depression. In terms of antidepressant treatment strategy, clinicians should initially choose an antidepressant within a class with the most favorable side-effect profile and few, if any, drug-drug interactions. ■

Additional Resources

Pathophysiology of Depression

Nemeroff CB. The State of Our Understanding of the Pathophysiology and Optimal Treatment of Depression: Glass Half Full or Half Empty? American Journal of Psychiatry; August 2020

Gillespie C, Szabo S, Nemeroff CB. Unipolar Depression. In: Rosenberg’s Molecular and Genetic Basis of Neurological and Psychiatric Disease, Sixth Edition (Rosenberg R, Pascual J, eds.). Elsevier; 2020

Medical Workup of Depressed Patients

Cohen BM, et al. Antidepressant-Resistant Depression in Patients With Comorbid Subclinical Hypothyroidism or High-Normal TSH Levels. American Journal of Psychiatry; July 2018

Pope HG, et al. Testosterone Gel Supplementation for Men With Refractory Depression: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. American Journal of Psychiatry; January 2003

Sotelo JL, Nemeroff CB. Depression as a Systemic Disease. Personalized Medicine in Psychiatry; March-April 2017

Pharmacogenomics in Depression Treatment Response

Zeier Z, Carpenter LL, Kalin NH, Rodriguez CI, McDonald WM, Widge AS, Nemeroff CB. Clinical Implementation of Pharmacogenetic Decision Support Tools for Antidepressant Drug Prescribing. American Journal of Psychiatry; September 2018

Zubenko GS, et al. Pharmacogenetics in Psychiatry: A Companion, Rather Than Competitor, to Protocol-Based Care—Reply. JAMA Psychiatry; October 2018

Goldberg JF, Nemeroff CB. Pharmacogenomics and Antidepressants: Efficacy and Adverse Drug Reactions. In: Psychiatric Genomics (Tsermpini E, Patrinos GP, and Alda M, eds.). Academic Press; in press

Antidepressant Treatment Studies

Trivedi, MH, et al. Evaluation of Outcomes With Citalopram for Depression Using Measurement-Based Care in STAR*D: Implications for Clinical Practice. American Journal of Psychiatry; January 2006.

Dunlop BW, Kelley ME, Aponte-Rivera V, Mletzko-Crowe T, Kinkead B, Ritchie JC, Nemeroff CB, Craighead WE, Mayberg HS, for the PReDICT Team. Effects of Patient Preferences on Outcomes in the Predictors of Remission in Depression to Individual and Combined Treatments (PReDICT) Study. American Journal of Psychiatry; June 2017

Farah A, Blier P. Combination Strategies for the Pharmacological Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. In: American Psychiatric Association Textbook of Mood Disorders, Second Edition. (Nemeroff CB, Schatzberg AF, Rasgon N, Strakowski SM, eds.) Washington, D.C.: APA Publishing; in press.

Rush AJ, et al. Combining Medications to Enhance Depression Outcomes (CO-MED): Acute and Long-Term Outcomes of a Single-Blind Randomized Study. American Journal of Psychiatry; July 2011

Fawcett J, et al. Clinical Experience With High-Dosage Pramipexole in Patients With Treatment-Resistant Depressive Episodes in Unipolar and Bipolar Depression. American Journal of Psychiatry; February 2016

New Treatments

Cole EJ, et al. Stanford Accelerated Intelligent Neuromodulation Therapy for Treatment-Resistant Depression. American Journal of Psychiatry; August 2020

Gunduz-Bruce H, et al. Trial of SAGE-217 in Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. New England Journal of Medicine; September 5, 2019

Sanacora G, Frye MA, McDonald W, Mathew SJ, Turner MS, Schatzberg AF, Summergrad P, Nemeroff CB. American Psychiatric Association Council of Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments. A Consensus Statement on the Use of Ketamine in the Treatment of Mood Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry; April 2017

Horowitz M, Moncrieff J. Are We Repeating Mistakes of the Past? A Review of the Evidence for Esketamine. British Journal of Psychiatry; May 27, 2020

Reiff CM, Richman EE, Nemeroff CB, Carpenter LL, Widge AS, Rodriguez CI, Kalin NH, McDonald WM. Psychedelics and Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychiatry; May 2020

Author’s Disclosure Statement

Research/Grants

National Institutes of Health (NIH)

Consulting (last 12 months)

ANeuroTech (division of Anima BV), Signant Health, Magstim, Inc., Navitor Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Intra-Cellular Therapies, Inc., EMA Wellness, Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Sage, BioXcel Therapeutics, Silo Pharma, XW Pharma, Neuritek, Engrail Therapeutics, Corcept Therapeutics Pharmaceuticals Company, SK Life Science, Alfasigma

Stockholder

Xhale, Seattle Genetics, Antares, BI Gen Holdings, Inc., Corcept Therapeutics Pharmaceuticals Company, EMA Wellness, TRUUST Neuroimaging

Scientific Advisory Boards

ANeuroTech (division of Anima BV), Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (BBRF), Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA), Skyland Trail, Signant Health, Laureate Institute for Brain Research (LIBR), Inc., Magnolia CNS, Heading Health, TRUUST Neuroimaging

Board of Directors

Gratitude America, ADAA, Xhale Smart, Inc.

Patents

Method and devices for transdermal delivery of lithium (US 6,375,990B1)

Method of assessing antidepressant drug therapy via transport inhibition of monoamine neurotransmitters by ex vivo assay (US 7,148,027B2)

Speakers Bureau:

None