Tardive Dyskinesia: Assessing and Treating a Debilitating Side Effect of Prolonged Antipsychotic Exposure

Abstract

Though second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) have a better safety profile than older antipsychotics, 1 in 5 patients on SGAs for a prolonged period develop tardive dyskinesia. The wider use of these medications by patients with mood and other nonpsychotic disorders makes this even more problematic.

Clinicians are understandably loathe to diagnose conditions over which they can exert little influence. Until recently, tardive dyskinesia (TD) has been one such example. It is usually iatrogenic from prolonged exposure to dopamine antagonists, making it hard even for astute prescribers to spontaneously notice characteristic TD movements while overcoming their own reflexive fears of culpability (“Did I previously discuss TD risk? Or formally assess it? How recently?”). When institutions do not mandate periodic Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) assessments, formal evaluations may slip the minds of practitioners who have limited time to assess and document psychopathology, treatment adherence, functioning, laboratory data, and adverse effects from increasingly common polypharmacy regimens.

The term “extrapyramidal symptoms” broadly captures movement disorders thought to originate from basal ganglia dysfunction that is typically drug induced. Dystonia, akathisia (motor restlessness), and Parkinsonism are commonly subsumed under this heading as phenomena that usually emerge acutely. TD is, by definition, a late-onset extrapyramidal syndrome. Tardive dystonia is considered to be a form of TD that involves prolonged, nonrhythmic contractions of specific muscle groups with increased motor tone.

Since at least the 1970s, the likely etiology of TD has been thought to reflect a supersensitivity to striatal postsynaptic dopamine receptors, presumably caused by chronic use of dopamine-blocking drugs. Some theorists challenge this explanation when noting that not all chronic antipsychotic recipients develop TD, yet most, if not all, develop postsynaptic dopamine receptor supersensitivity. Others suggest that antipsychotic-induced presynaptic noradrenergic overactivity may predispose some long-term antipsychotic recipients to TD. Prolonged exposure to dopalytic drugs may also cause damage to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) interneurons and cholinergic neurons (hence, anticholinergic drugs may worsen TD). Genetic vulnerabilities also likely play a role.

TD More Common After One Year of SGA Use

By some estimates, about 1 in 5 individuals taking a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) for a prolonged period may develop TD, as compared with about 1 in 3 taking only a first-generation antipsychotic (FGA). The correlation between a specific length of time or dose and development of TD is not known. However, a recent meta-analysis calculated an annualized risk for TD of 2.6% with SGAs as a class and 6.5% with FGAs. A precise incident rate is hard to know because reported cases in postmarketing pharmacovigilance studies do not take into account the denominator of all exposed individuals, the duration of exposure, and use of multiple possible causal agents. Meta-analyses based on controlled trials of at least one year’s duration tend to project an annual incident rate for TD of about 5% in adults older than age 50, but multi-year prospective studies are lacking. TD is rare when antipsychotic exposure is less than three months (or less than one month in adults older than age 60) and tends to be more common after at least one to two years of near-persistent use. Cumulative risk includes all lifetime use of any dopamine-blocking drugs (including antiemetics such as metoclopramide and prochlorperazine). Little is known about whether some dopalytic agents—such as D2 receptor “tight binding” drugs versus “loose binding” drugs—have an inherently higher risk than others (tight binding, not loose binding, is thought to increase TD risk), and in rare instances TD has been reported only from exposure to nondopalytic drugs, such as selective serotonin/serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs/SNRIs).

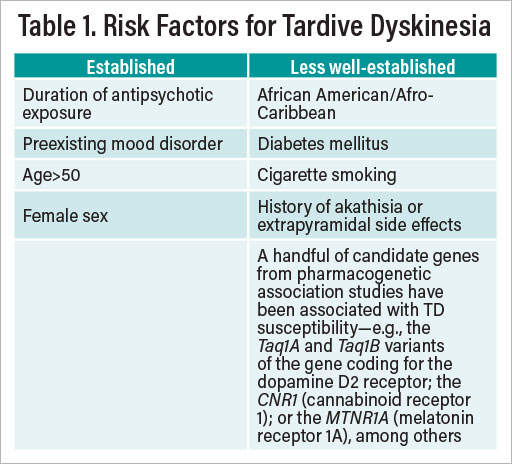

Factors that increase a patient’s risk for developing TD are summarized in Table 1.

Timing and implementing a patient discussion about TD can be delicate and tricky. Calling a patient’s attention to a possibly permanent or untreatable adverse effect from a drug that they might rather not be taking could feel like an implicit invitation for future nonadherence. Pragmatically, TD needs to be considered alongside a litany of other possible adverse effects from SGAs (such as weight gain and metabolic dysregulation) as well as other co-prescribed medications. A discussion about long-term drug risk-benefits and management is often best initiated in a dedicated, shared decision-making fashion after acute symptoms have waned. Of paramount importance is the psychiatrist’s ability to convey a sense that he or she is empathic, cognizant, flexible, and vigilant. Consider an overture such as the following:

“We both seem to agree you’re now feeling better. This may be a good time for us to discuss the best plan going forward to keep you well—both to avoid a relapse and to make sure we’re staying on top of possible side effects. All medicines can have side effects, so if either of us becomes concerned about a possible side effect, let’s discuss it. Some side effects are common and go away with time. Some are just annoying but are not dangerous and can be managed. Together we need to make sure we’re protecting you from serious side effects. If a possibly concerning side effect comes up, we should decide together whether or not the benefits of continuing a medicine outweigh its risks. Almost always, there will be options we can think through together.”

A planned discussion initiated in this way allows one to set the stage for anticipating and managing current and future side effects; reviewing the outcome of suspected past side effects; and gauging their transience or persistence, spuriousness, dose relatedness, and typical occurrences early versus late after starting a medicine. To continue:

“Most side effects, as well as benefits, make themselves known sooner than later. Less often, some come along after long-term use of a medicine. One of these, related to medicines that affect a chemical in the brain called dopamine, can involve problems controlling muscle movements in your mouth, face, or elsewhere called tardive dyskinesia. Let me tell you about it and what we should look out for over time in case it starts to appear.”

Patients May Not Be Aware of Abnormal Movements

What about discussions prompted by the realization that abnormal movements are already present due to the medication, particularly if there has been no previous dialogue? A direct discussion should be factual and attentive, nonalarmist, and inquisitive. The following example provides a simple entre to performing an AIMS exam (described further below):

“I notice as we’re talking that there are times when I see your lips or tongue moving differently than usual. May I ask you more about this? Are you aware of it? Is your mouth dry? Have you had any dental problems? If not, let’s take a few moments so I can assess this more fully.”

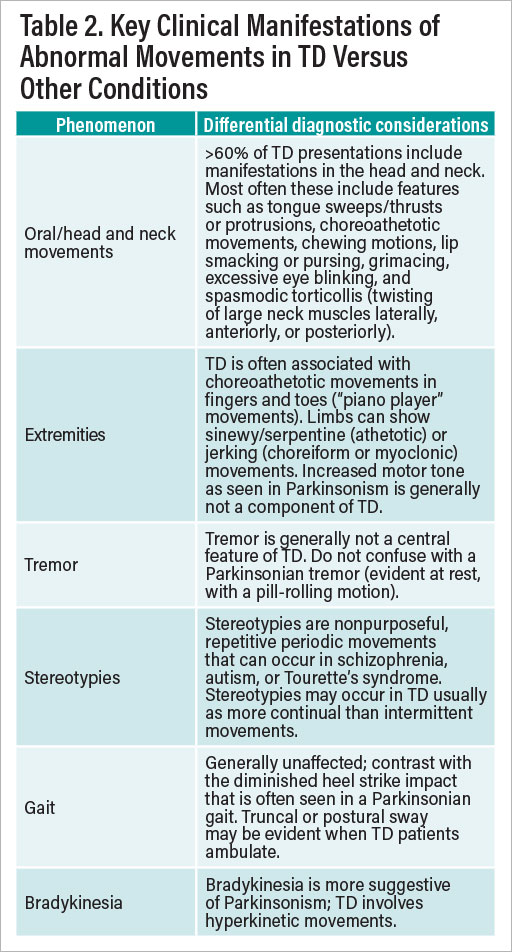

Psychiatrists may sometimes forget that every mental status exam they perform includes an assessment of motor function, which by definition includes possible features of TD. Patients at risk for TD may not always flag concerns about abnormal movements, given that schizophrenia patients with TD are often unaware of its presence, regardless of their degree of insight (or lack thereof) about their psychiatric symptoms. Psychiatrists themselves also may not always feel comfortable differentiating the various types of movement disorders or discriminating TD from other adverse motor effects such as tremor, akathisia, motor tics, or Parkinsonism. Table 2 summarizes key points about the kinds of abnormal movements of which one should be most aware on an initial assessment in a patient with possible TD.

An AIMS exam provides a more thorough and quantitative regional assessment of oral/facial, truncal, and limb/finger/toe movements, as well as global severity, incapacitation, and distress. Individual items are scored from 0 (none) to 4 (severe). A “positive score” is defined as a rating of 2 or greater on the first seven items for two or more movements, or ratings of 3 or 4 on a single movement. A total AIMS score is the sum of the first seven items, ranging from 0 to 28. Performing an AIMS exam usually takes less than 10 minutes. TD experts generally advise conducting a formal AIMS exam every three to six months for patients taking dopalytic drugs.

Useful clinical points about TD include the following:

Antipsychotic dosage reductions do not ameliorate TD, although dosage increases may mask it.

It is unknown whether, or how often, antipsychotic cessation eliminates TD (although in younger patients with less lifetime antipsychotic exposure, TD may be more likely to improve after stopping antipsychotics). Abruptly stopping an antidopaminergic drug in a patient who has TD often leads to initial worsening of abnormal movements.

Abruptly stopping an antipsychotic drug in any patient may cause a withdrawal dyskinesia.

Patients for whom continued use of dopamine-blocking drugs is deemed elective may be better candidates for stopping a presumed offending agent and observing for possible improvement in abnormal movements.

In patients with chronic psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia, antipsychotics should not routinely be stopped solely because a patient develops TD. Discontinuation should be considered only if the benefits of ongoing antipsychotic treatment (and risk for relapse of psychosis) are outweighed by risks of antipsychotic continuation.

TD movements disappear during sleep.

Risk for TD with SGAs is not so substantially less than with FGAs as was originally presumed.

Anticholinergic drugs such as benztropine or diphenhydramine (sometimes used to manage drug-induced Parkinsonism) can make TD symptoms worse and ideally should be stopped in patients with TD.

Recognizing and managing TD become all the more complex as the use of SGAs rises among patients with primary mood rather than psychotic disorders, often making the rationale and justification for long-term dopamine-blocking drugs more difficult. In both bipolar disorder and major depression, there is virtually no guidance from drug manufacturers, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), or even the clinical trials literature for anticipating and implementing time-limited versus indefinite SGA use after an acute condition resolves. SGA manufacturers that sponsor clinical trials have little incentive to undertake randomized trials intended to demonstrate when their products are no longer necessary and should be stopped. Nevertheless, at least in the case of bipolar disorder, a small database of randomized discontinuation trials suggests that after 24 weeks, there are limited long-term prophylactic benefits above and beyond those of a long-term mood stabilizer alone. Less is known about the optimal duration of an adjunctive SGA during antidepressant therapy for major depression.

VMAT-2 Inhibitors the ‘Gold Standard’

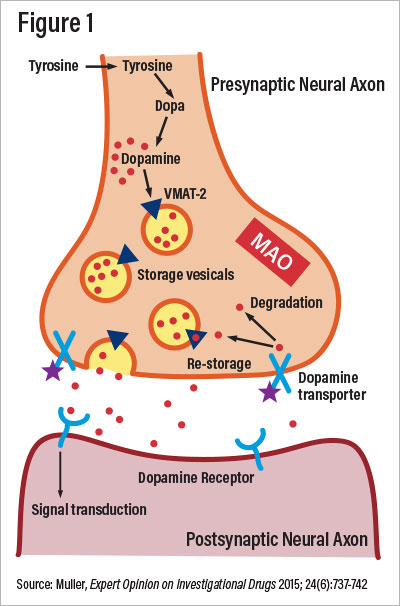

Since the FDA approved both valbenazine and deutetrabenazine in 2017 for treatment of TD and vesicular monoamine transporter-2 (VMAT-2) inhibitors as a class, they have become the new “gold standard” treatment. VMAT-2 is a presynaptic membrane protein that chaperones catecholamines from the cytosol to synaptic exocytosis. Irreversible blockade of VMAT-2 decreases postsynaptic striatal dopamine receptor stimulation, as illustrated in Figure 1.

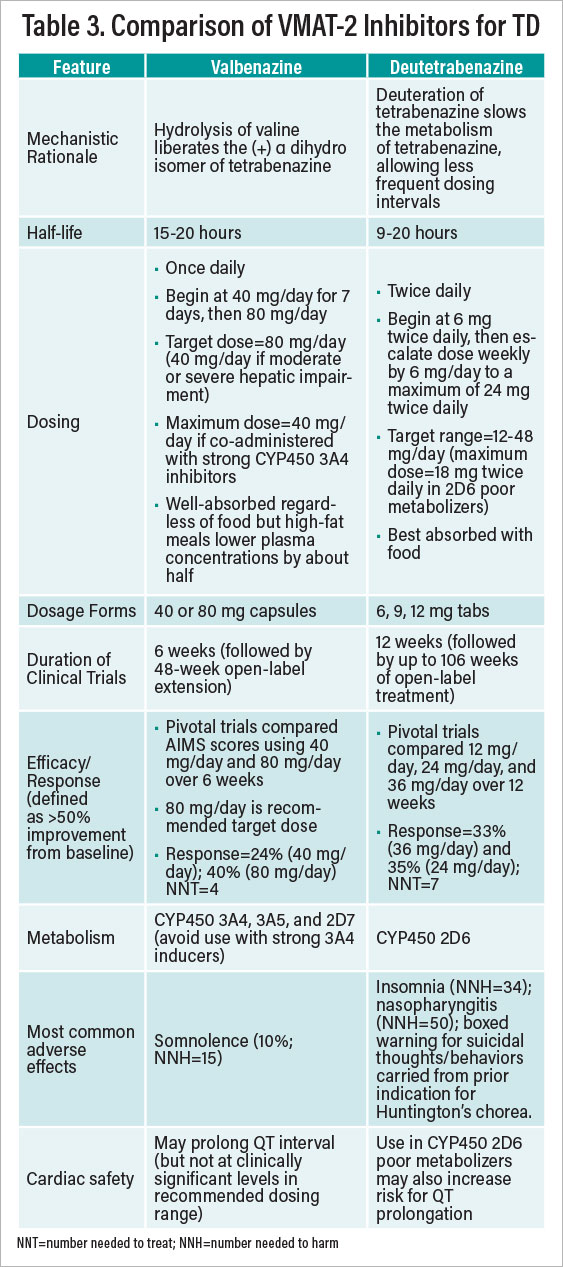

Valbenazine and deutetrabenazine have not been compared in head-to-head trials. Table 3 provides a comparative summary of information about their respective uses. Choosing one VMAT-2 inhibitor versus the other is a matter of clinical judgment. Some psychiatrists might favor the once-daily dosing of valbenazine, while others may favor the wider dosing range with deutetrabenazine. No studies have examined whether nonresponders to one agent may fare better if switched to the other. Several general caveats are worth noting regarding VMAT-2 inhibitor treatment of TD:

Discontinuing a VMAT-2 inhibitor after successful elimination of hyperkinetic movements usually causes prompt return of TD symptoms; the treatment is thus likely not “curative.”

VMAT-2 inhibitors can exacerbate underlying Parkinsonism or akathisia.

Combining VMAT-2 inhibitors with monoamine oxidase inhibitors is discouraged because monoamine oxidase is needed to degrade presynaptic dopamine (whose transport into the synaptic cleft is blocked by VMAT-2 inhibitors).

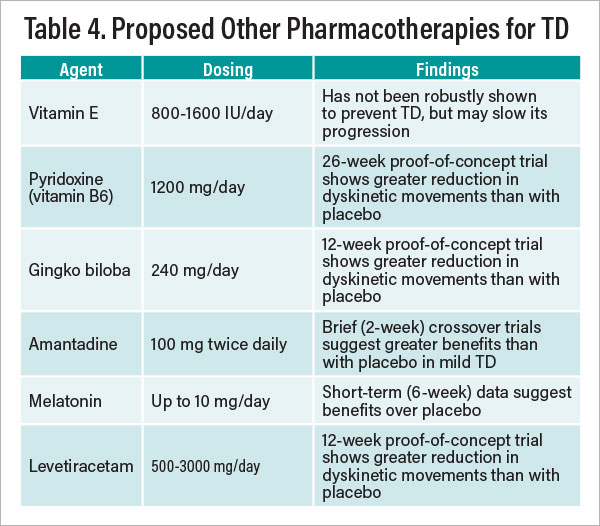

Apart from VMAT-2 inhibitors, a number of compounds have been studied with varying degrees of demonstrated efficacy for managing TD, based mostly on a literature from the 1990s and early 2000s. Table 4 presents a brief summary of those agents for which there are supportive data showing effectiveness in countering or forestalling TD based on at least one published randomized trial. Findings with most compounds listed have not been replicated in multiple controlled trials. The theoretical rationale for some of the agents listed involves their putative antioxidant or free radical scavenging properties. Additionally, open trials have suggested possible value injecting botulinum toxin A for facial-lingual-masticatory focal TD. Also noteworthy are observational (nonrandomized) reports and case studies suggesting that clozapine may reduce dyskinetic symptoms in TD patients, although no randomized trials have as yet been undertaken to test that hypothesis.

Some experts advocate for the favored use of “loose” D2 binding dopamine antagonists—quetiapine or clozapine—if feasible, when an ongoing antipsychotic is needed in patients with TD. The SGA lumateperone is notable for its 60-fold greater binding affinity for 5HT2A than D2 receptors, making it a potentially attractive option for patients with high susceptibility to adverse motor effects from striatal dopamine blockade. Pimavanserin, currently approved by the FDA for psychosis in patients with Parkinson’s disease, is a pure 5HT2A antagonist with no known dopalytic effects. It remains under investigation for schizophrenia and, if approved, may be a compelling option for patients with TD.

Conclusion

Potentially disfiguring and socially stigmatizing, TD remains a vexing problem linked with prolonged use of all dopamine-blocking drugs. The availability and use of VMAT-2 inhibitors have ushered in a new era of treatment, alongside renewed vigor in the recognition of and screening for TD.

Psychiatrists should remain attentive to the risks and benefits of long-term use of dopamine-blocking drugs (as with all psychotropic medications), particularly in the absence of long-term safety and efficacy data as a primary or adjunctive therapy in patients with nonpsychotic mood or other psychiatric disorders. ■