Naltrexone-Bupropion Combination May Reduce Methamphetamine Use

Abstract

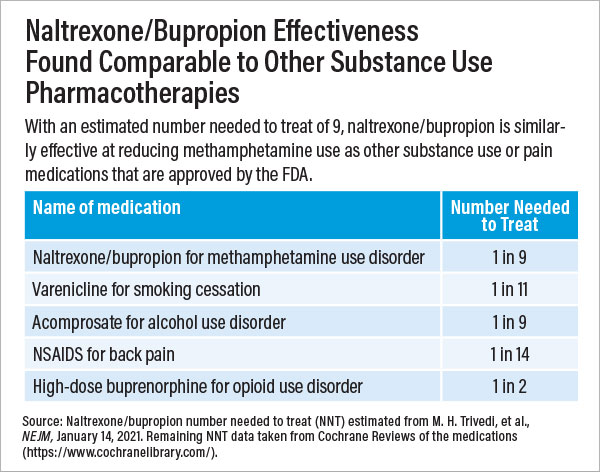

Data from a phase 3 clinical study suggest that the combination of these two medications can help 1 in 9 people with methamphetamine use disorder.

Extended-release naltrexone in combination with bupropion can effectively treat some people with methamphetamine use disorder, according to a study involving over 400 participants. As reported in the New England Journal of Medicine, 13.6% of participants with moderate or severe methamphetamine use disorder who took the extended-release naltrexone/bupropion combination significantly reduced or stopped their methamphetamine use compared with 2.5% of those who took placebo.

Though overshadowed by the ongoing opioid crisis, the illicit use of methamphetamine and its tragic consequences have risen dramatically over the past decade. A recent analysis appearing in JAMA Psychiatry found that deaths involving methamphetamine rose more than fivefold between 2011 and 2018. And unlike the multiple medication options available for patients with opioid use disorder, no medications have received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for treating methamphetamine use disorder.

“It’s not just that this illness has no approved medications,” said Madhukar Trivedi, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and lead investigator on this study. “Clinical studies to date have not even produced results that might hint at a potential medication.”

Those previous failed clinical efforts included trials separately testing the effectiveness of naltrexone (used to treat opioid and alcohol use disorders) and bupropion (an antidepressant also approved for tobacco use disorder) at reducing methamphetamine use. Trivedi and colleagues surmised that combining the medications might provide some synergy—naltrexone works by reducing the euphoria felt after taking certain substances while bupropion targets dysphoria, or the discomfort and unease that arise during withdrawal.

The investigators enrolled 403 adults aged 18 to 65 who met the DSM-5 criteria for moderate or severe stimulant use disorder (methamphetamine type) for this placebo-controlled study. “On average, these participants had used methamphetamine on 27 of the previous 30 days,” Trivedi noted. “We were enrolling people severely affected by this drug.”

The trial was divided into two six-week stages. In the first stage, 109 participants were randomly assigned to receive 380 mg of injectable naltrexone every three weeks combined with 450 mg oral bupropion once daily, while the other 294 received matched placebo injections and pills. After six weeks, the 225 participants in the placebo group who remained in the trial after showing no response to placebo were re-assigned: 114 received naltrexone/bupropion during stage 2, while 111 continued to receive the placebo regimen. The participants visited the clinic twice a week to provide urine samples; complete clinical assessments; and receive injections, when needed.

Participants whose urine tested negative for methamphetamine during at least three out of four collections at weeks 5 and 6 were considered to have responded to treatment. After the first stage, 16.5% of participants in the naltrexone/bupropion group and 3.4% in the placebo group responded to treatment. In the second stage, 11.4% of participants in the naltrexone/bupropion group and 1.8% in the placebo group responded to treatment. Pooled together, the results pointed to an 11.1% difference between the medication and placebo response; put another way, for every nine patients given naltrexone/bupropion, one would show a meaningful reduction in methamphetamine use.

Trivedi noted this response rate is on par with the rates achieved by several FDA-approved psychiatric medications, such as those for smoking cessation, alcohol use disorder, nonopioid pain relief, and obesity. Additionally, he noted that these results were seen in study participants who did not receive any other supportive therapies for substance use, such as behavioral counseling.

Adverse events were common among participants in both groups during the trial, but most of these events were mild to moderate in severity and reflected typical substance use withdrawal symptoms. Adverse events that were more common in people taking naltrexone/bupropion included nausea, vomiting, tremors, malaise, and loss of appetite.

Nora Volkow, M.D., director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (which funded the study), hailed these findings.

“After decades of futility, we finally have a positive signal, and it is a large effect,” she said. “In clinical practice, physicians can boost the response rate even more by treating comorbid problems like depression or insomnia and providing additional support like counseling or contingency management,” she said. (Contingency management uses motivation and rewards such as gift cards to encourage treatment adherence.)

Volkow said that an important area of follow-up is to test the naltrexone/bupropion combination in people who use methamphetamine in combination with opioids. Many people use both drugs concurrently, whether intentionally or inadvertently by taking methamphetamine laced with fentanyl.

Volkow told Psychiatric News that Alkermes, the company that manufactures injectable naltrexone, has reached out to the FDA to determine what additional data are needed to seek an expanded indication for its product.

She hopes the approval process will be quick but noted that the FDA is still dealing with a significant number of reviews related to COVID-related vaccines and medications. In the interim, she pointed out that physicians can prescribe this medication combination off label, though that may mean patients must pay for it themselves.

“We know that methamphetamine problems hit socioeconomically disadvantaged communities the hardest, so off-label availability limits the people who can benefit,” she said. The recent JAMA Psychiatry analysis on methamphetamine-related deaths (on which Volkow was a co-author) highlighted that American Indian and Alaska Native adults had the highest rates of overdose deaths compared with Black, White, and Hispanic adults.

Both the naltrexone/bupropion clinical trial and methamphetamine overdose analysis were funded by NIDA. Alkermes provided naltrexone at no cost for the clinical trial as part of an agreement with NIDA. ■