Why Do We Behave the Way We Do? Speaker to Pull Threads Together

Abstract

The sobering side of the neurobiological revolution is that behavior is largely determined—with little or no room for free will—by the psychological, physiological, and evolutionary forces science is now decoding, says Robert Sapolsky, Ph.D.

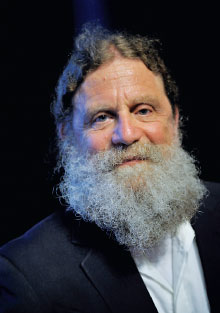

The message that neuroscientist, primatologist, and best-selling author Robert Sapolsky, Ph.D., carries about the neuroscientific revolution of our time is both hopeful—promising a new understanding of behavior and more effective tools for treating people with mental illness—and yet also profoundly sobering, challenging our notions about free will.

Sapolsky will bring his message to APA’s 2021 online Annual Meeting, where he will deliver the closing plenary address on Monday, May 3. His 2017 book, Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Our Worst, won the Phi Beta Kappa Award for Science and was listed among Best Books of the Year by the Washington Post, New York Times, and Wall Street Journal.

In the book, Sapolsky focuses, with passionate interest, on the unique human capacity for cruelty and violence and asserts that human beings are at once the most creatively altruistic creatures and—by far—the most violent.

Synthesizing findings from a range of disciplines, Sapolsky describes how any behavior is shaped by events in the environment and responses by the human organism in the immediate seconds prior to the behavior. But these responses are shaped in the hours or days before the behavior by psychological, hormonal, and other physiological responses (usually unconscious) and in the weeks and months and years before that by social and cultural factors—all the way back to childhood, infancy, and the womb.

And these factors, too, are shaped even earlier by epigenetic changes transmitted across generations and by events all the way back to “evolutionary pressures played out over the prior millions of years that got the ball rolling.”

“We are biological organisms, but the way all the pieces come together is wildly nonlinear and unpredictable. But it doesn’t mean [these influences] are any less understandable,” says Robert Sapolsky, Ph.D.

In an interview with Psychiatric News, Sapolsky explained that neuroscience is increasingly weaving all of these threads together, with results that promise a greater understanding of human behavior and solutions for “bad” behavior. Most passionately, for instance, Sapolsky believes that these developments argue for “completely deconstructing the whole criminal justice system and trashing it to come up with something radically different for how we deal with norm violations.”

For psychiatrists, the neuroscience revolution stitching together the forces that shape the human organism promises more effective tools and treatments for behavior caused by mental illness.

“What is going to do wonders is brain imaging showing how you go from adverse environment, to increased stress levels, to increased oxidative damage, to shortened telomeres in your white blood cells,” he said. How the patient’s resulting depression or anxiety is most effectively treated is just a function of what tools are available.

“Sometimes you want to change the epigenetics of someone’s hippocampus using a viral vector, sometimes by getting the patient into the right support group,” Sapolsky said.

Yet the sobering side of these revelations, the author believes, is that our behavior is largely determined—with little or no room for free will—by all of the psychological, physiological, and evolutionary forces that science is now decoding.

When asked what he hopes psychiatrists will take away from his lecture, Sapolsky said: “How mechanistic we are, how much we are the outcome of random biological luck, and how much those influences are nonetheless not easily understood in straitjacketed, reductionist ways. We are biological organisms, but the way all the pieces come together is wildly nonlinear and unpredictable. But it doesn’t mean [these influences] are any less understandable. It just means we are going to need radically new tools.”

He added, “It also doesn’t mean we are any less determined.”

He sees all too readily how such a deterministic viewpoint can lead to a kind of existential despair, and Sapolsky’s new book in progress, Determined: A Science of Life Without Free Will, will seek to decipher a science for how to make moral sense of determinism, he said.

Sapolsky may have previewed this attempt in the concluding pages of Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Our Worst when he suggests that those of us who have received a lucky roll of the evolutionary, genetic, and psychosocial roll of the dice have little choice but to take up the task of repairing the world.

“Eventually it can seem hopeless that you can fix something, make things better. But we have no choice but to try. If you are reading this, you are probably ideally suited to do so. You have amply proven you have intellectual tenacity, you probably also have running water, a home, adequate calories, and low odds of festering with a bad parasitic disease. You probably don’t have to worry about … warlords or being invisible in your own world. And you’ve been educated.

“In other words, you’re one of the lucky humans. So try.” ■

Sapolsky’s lecture will be held Monday, May 3, from 10 a.m. to 11 a.m.