Addressing Maternal Mental Health: Progress, Challenges, and Potential Solutions

Abstract

Much needs to be done to reduce the morbidity and mortality of individuals* before and after they give birth, but valuable resources and programs are now available to reach that goal.

Kai receives her obstetric care at a large rural practice in Georgia. She screened at risk for depression 14 weeks into her pregnancy. Not knowing how to respond and not having referral sources, her obstetric practice recommended that she call her insurance company for a therapy referral. At 24 weeks of her pregnancy, Kai was feeling worse and asked her obstetric physician for an antidepressant, reporting a three-month wait for therapy through her insurance company. Not comfortable prescribing an antidepressant, the obstetric physician referred her to a psychiatrist; however, the wait time was four months. Still waiting for treatment a month after giving birth, Kai deteriorated, attempted suicide, and was hospitalized in a psychiatric ward, causing additional trauma as she was separated from her infant and had to stop breastfeeding before she wanted.

Situations like that of Kai occur all too frequently in clinics across the United States. Perinatal individuals share the same risk of psychiatric and substance use disorders as those who are not pregnant or postpartum. However, some consequences of these conditions may differ from those of other groups. For example, when pregnant individuals become psychiatrically ill, they may be less likely to seek and obtain prenatal care. After delivery, family disruptions may occur. This can begin with difficulties in mother-infant bonding, and the impact can continue beyond infancy. Children of mothers with mood or anxiety disorders are at increased risk of having their own mood, anxiety, or behavioral disorders.

Mental and substance use disorders are on par with infection as a leading cause of preventable maternal mortality in the United States. The most recent report from 14 maternal mortality review committees found that mental health causes, which include suicide and drug overdose, accounted for nearly 9% of pregnancy-related deaths, more than those caused by hypertensive crises like preeclampsia. The United States is also the only high-income nation in the world with an increasing maternal mortality rate (Psychiatric News).

The increasing recognition of mental and substance use disorders as a contribution to maternal mortality is a major step forward in appreciating the challenges in women’s health. Conversations with patients about perinatal health that address both physical and mental illnesses are needed and can contribute to reducing maternal morbidity and mortality.

Expanding Our View of Perinatal Mental Health

Despite the many psychiatric illnesses that can occur during the perinatal period, much of the attention and focus has been specific to postpartum depression. Determining what is “postpartum depression” can be tricky. Historically, a postpartum label was assigned if the depressive episode was present during the six-month or even the 12-month period after delivery. DSM-IV operationalized a postpartum modifier for major depressive episode if it occurred during the month after delivery, with the rationale that this would link the biology of depression to physiological changes occurring after childbirth. However, about half of individuals who are depressed postnatally experienced depressive symptoms or a depressive episode during pregnancy. Thus, DSM-5 changed the modifier to “perinatal” and stipulated the presence of symptoms during pregnancy or in the month after delivery. The optimal way to operationalize a postpartum or perinatal depressive episode remains controversial and needs further exploration.

Although identifying and addressing depression during pregnancy or after delivery is critical, obstetric professionals need to know that other mental and substance use disorders are common during pregnancy and the first year postpartum. Anxiety disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) occur in up to 30% and 15% of perinatal and postpartum women, respectively. Studies have also found that up to a fifth of women who screen positive for postpartum depression have bipolar disorder. Detection of bipolar disorder is especially critical because its treatment differs from that for unipolar depression. Substance use also frequently occurs during and after pregnancy and is a major contributor to maternal mortality.

As we open our eyes to the risk of other psychiatric illnesses, we must consider the contextual factors in which these conditions occur. Social determinants of health are factors that promote and/or exacerbate illness; they also may hinder individuals’ efforts to seek treatment for mental and substance use disorders. Thus, to adequately address mothers’ mental health needs, health care professionals and policymakers need to expand their focus beyond the diagnoses and treatment of specific illnesses. Areas that need to be probed and potentially addressed include personal and family psychiatric history, unplanned pregnancy, financial challenges, social isolation, limited social supports, and exposure to domestic violence.

The COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has created unprecedented stress for pregnant individuals and elevated the risk of depression and anxiety even further. Due to social distancing, it has become a challenge to utilize usual support systems, often leaving people feeling isolated. Many worry that (1) they, their unborn baby, or their newborn may be infected with COVID-19; (2) they might not be allowed to have a support person accompany them during labor and delivery; and (3) they might be separated from their infant after delivery. It has always been difficult for perinatal individuals experiencing anxiety or depression to access appropriate psychiatric care. The current situation—with an increase in the range and intensity of mental health challenges coupled with increased pressure on the health care system—has made it even more challenging for perinatal individuals to access mental health care.

The pandemic has also widened health inequities. Black, Asian, Hispanic/Latina/o, and/or multiracial individuals were at higher risk for adverse mental health outcomes and disruptions in accessing care before the pandemic. Pandemic-related hospitalizations and deaths are also having a greater effect on these populations compared with White individuals. Efforts to address perinatal mental health must take into account health and mental health inequities.

Gaps in Perinatal Mental Health Care

Recognizing that mental and substance use disorders during the perinatal period are a major public health problem, professional organizations and policymakers now recommend universal screening for depression. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that all pregnant and postpartum individuals be screened for depression and that psychiatric care and obstetric care be integrated. For example, the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care developed a Maternal Mental Health patient safety bundle. The bundle is well aligned with the screening recommendation of ACOG and the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force and provides guidance on incorporating mental health screening, treatment, referral, and follow-up into routine maternity care.

However, screening alone is insufficient. Despite consistent recommendations across organizations, the care of perinatal women with a psychiatric illness falls below today’s standards. Estimates suggest that only 16% of women who screen positive receive psychiatric treatment. As illustrated with the example of Kai, the mental health care pathway—screening, assessment, and treatment until symptom remission—is laden with gaps and barriers.

The implementation of screening recommendations and patient safety bundles is uniquely challenging. Obstetric professionals often do not have ready access to the resources they need to detect, assess, and manage perinatal mood or anxiety disorders.

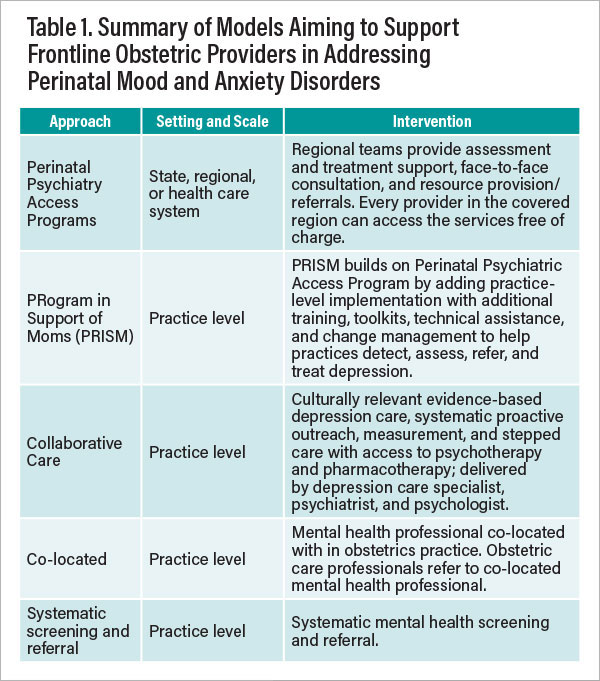

In response, models have been developed to close gaps at the patient, provider, and systems level to develop interventions for addressing depression. These were devised with a clear understanding of the major barriers to addressing perinatal mental and substance use disorders including the lack of available mental health professionals to whom to refer women and inadequate training, capacity, and resources among obstetric professionals and practices to ensure appropriate psychiatric assessment, treatment, and follow-up. Scalable approaches for building the capacity of frontline obstetric professionals to address perinatal mood and anxiety disorders are sorely needed.

Models for Integrating Perintal and Mental Health Care

The intent of these models is to leverage mental health professionals and other resources to build frontline provider support and capacity in the delivery of quality psychiatric care for individuals in primary care settings. The areas targeted for support include assistance with detecting, assessing, treating, and/or referring individuals with perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (see Table 1). For example, the Perinatal Psychiatry Access Program Model increases health care professionals’ willingness and ability to screen for and manage patients with depression and comorbidities. The Perinatal Psychiatry Access Program Model began with the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program (MCPAP) for Moms (Psychiatric News). Launched in 2014, MCPAP for Moms offers obstetric practices throughout Massachusetts with trainings, access to immediate resource provision/referrals, and psychiatric telephone consultation to help them address perinatal mental and substance use disorders.

With program costs as low as $1.16 per month per woman in Massachusetts, MCPAP for Moms has become a national model for perinatal mental health care. It inspired federal legislation that resulted in the Health Services Research Administration’s funding seven other states to develop their own Perinatal Psychiatry Access Programs. (These states are Florida, Kansas, Louisiana, Montana, North Carolina, Rhode Island, and Vermont.) Additional state and regional programs have emerged through various funding mechanisms, resulting in 16 access programs across the United States. Collectively, these programs cover more than 1.44 million of the 3.79 million births each year in the United States. MCPAP for Moms, the legislation it inspired, and the HRSA programs modeled on it are included in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2020 Action Plan to Improve Maternal Mental Health in America.

Implementing Integrated Care at the Practice Level

Despite the success and low cost of Perinatal Psychiatry Access Programs, additional proactive practice-level interventions are needed to fully integrate care for mental and substance use disorders into obstetric care. For example, obstetric practices do not screen consistently, and processes for monitoring symptoms do not fit into their workflow. Training in diagnostic evaluations is also limited, and some individuals may be misdiagnosed with unipolar depression when actually they suffer from bipolar, anxiety, and/or a substance use disorder. Obstetric practices also need proactive assistance to help them fully integrate depression care into their workflow. Access to evidence-based psychotherapy is also often a challenge. Even when resources for psychiatric treatments are available off site, less than half of patients follow up with an initial referral.

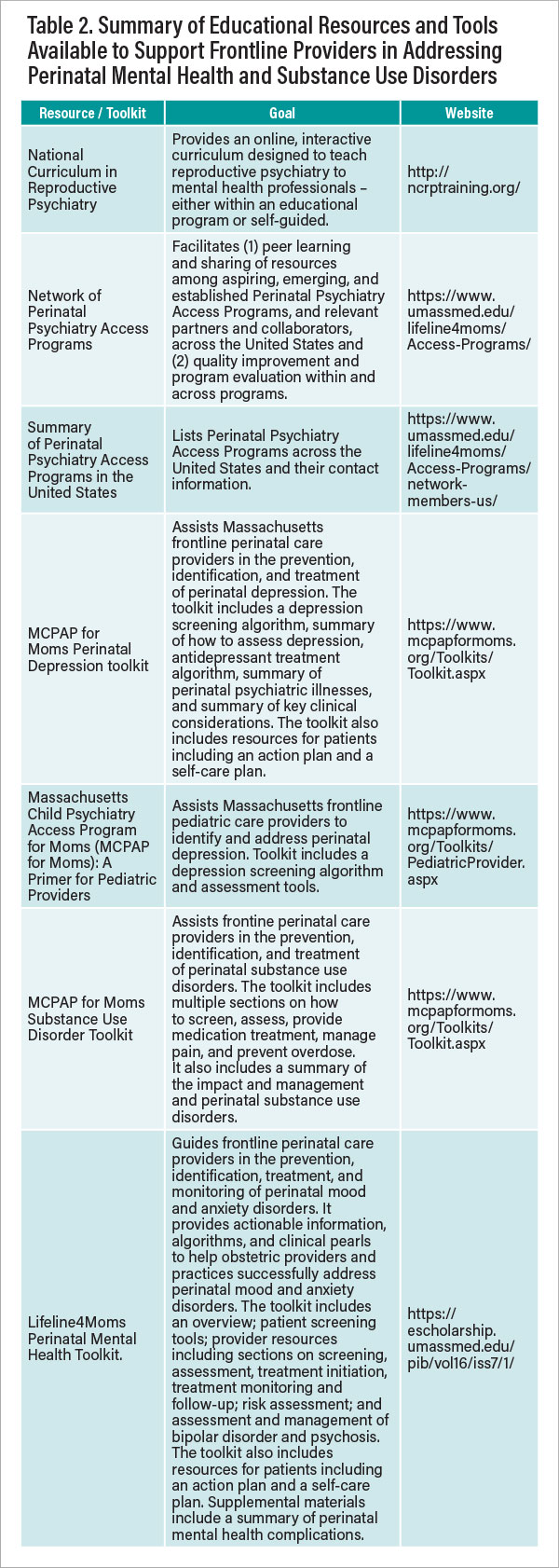

Proactive practical interventions were developed to build on and be synergistic with Perinatal Psychiatry Access Programs. Such approaches provide intensive support to help obstetric practices implement and sustain care for women with perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (see Table 1). Practices need rigorous training, implementation protocols, and assistance to fully integrate mental health screening, assessment, and follow-up into the workflow of obstetric practices. Numerous toolkits and education resources are now available (see Table 2). Networks, curriculums, toolkits, training materials, and protocols help both obstetric and psychiatric practices provide evidence-based treatment for women with perinatal mental health and substance use disorders.

Addressing Health Inequities When Implementing Integrated Care

We cannot adequately address perinatal mental or substances use disorders without considering and addressing the social determinants of health that are inextricably linked to racial and ethnic health disparities. Problems like racial discrimination; neighborhood crime; and financial, food, and housing insecurities are all associated with low engagement in prenatal care among women of color, leading to increased rates of fetal, neonate, and infant mortality. Screening for social determinants of health may help illuminate factors contributing to health inequities as they relate to the assessment and treatment of mental illness in perinatal individuals. Addressing social determinants of health is uniquely challenging because they have not been included in the traditional medical model. We need to work to ensure that all populations of perinatal individuals are screened for mental and substance use disorders and that those who screen positive receive a sensitive and culturally humble response.

Vision for Integrated Obstetric and Mental Health Care

The following summarizes our vision of how integrated care can change the trajectory for Kai and transform perinatal mental health care.

After learning about the recommended depression screening practices from professional society meetings, the OB-GYN practice in Georgia decides to implement screening, assessment, and treatment of perinatal mental and substance use disorders. The practice had been hesitant to screen consistently for depression because the staff do not know how to assess or treat these illnesses. They also do not have an adequate referral base for patients who need psychotherapy. The practice learns about the state’s recently launched Perinatal Psychiatry Access Program. The practice participates in a training session and learns how to implement screening, assessment, and treatment of individuals with perinatal mental and substance use disorders. They also learn how their Perinatal Psychiatry Access Program can help them respond to positive screens. Armed with additional resources and tools, they integrate mental health screening, assessment, and treatment into their workflow.

Kai then returns to the same obstetric practice four years later for her second pregnancy. She completes a screen for depression at 14 weeks’ gestational age. The physician reviews the results and, guided by training from the Perinatal Psychiatry Access Program, discusses treatment options, recommends therapy, and prescribes an antidepressant for which there are reassuring data regarding safety for patients who are pregnant and/or breastfeeding. Kai starts medication and is connected to a therapist and support group through the practice’s access program. At 30 weeks into her pregnancy, Kai feels better, with full remission of symptoms.

As illustrated in the case of Kai, Perinatal Psychiatry Access Programs aim to improve perinatal mental health care by building frontline provider capacity. These programs have an impact on state and national policies regarding perinatal mental health; they can lead to increased access to perinatal mental and substance use care for hundreds of thousands of patients. While screening is important, it is only the first step in the perinatal mental health care pathway. For this reason, the care must happen within systems to ensure that patients are referred for and participate in further treatment.

Maternal mental health is a core aspect of women’s overall health. When perinatal individuals have mental or substance use disorders, they are at risk of negative obstetric outcomes. Appropriate policies and health care models that enable sustainable integration of perinatal mental and substance use care into obstetric care are needed. Such policies can promote positive outcomes, reduce maternal mortality, and improve the overall health of these women and their families. As our nation gears up to address the maternal mortality crisis, we have an opportunity to impact the health of our nation’s mothers, children, and families by improving perinatal mental health. ■

*Recognizing the gender diversity within the group of patients receiving obstetrical care, we describe the population of interest as “individuals.”

Resources

General educational resources and toolkits | |||||

Perinatal Psychiatry Access Programs

| |||||

PRogram in Support of Moms (PRISM)

| |||||

Systematic screening and referral

| |||||