Ezogabine Shows Promise as Antidepressant

Abstract

A 45-subject clinical study suggested ezogabine is associated with rapid and robust improvements in anhedonia symptoms, though accompanying MRI data failed to detect any changes in the brain’s pleasure centers.

A study in the American Journal of Psychiatry has found evidence to suggest that the anticonvulsant ezogabine might be a promising antidepressant candidate, especially for patients who have a difficult time experiencing pleasure, or anhedonia.

Adults with depression and high levels of anhedonia who received ezogabine for five weeks experienced superior symptom improvements compared with those who received placebo. However, neuroimaging analysis failed to definitively show how ezogabine produced a change in brain activity. This may slow down clinical development of the medication as funding agencies want more biomarker data for drug candidates.

Ezogabine, also known as retigabine, is an anticonvulsant that binds to proteins known as KCNQ potassium channels. These channels control the flow of electrical currents across neurons but have also been implicated in resilience to stress. For example, studies in mice have found that animals that did not develop depressive behaviors in response to stressful situations had more KCNQ channels in the reward centers of their brains than animals that developed stress-induced depressive behaviors. Further studies in mice then showed that KCNQ activators like ezogabine can make the mice more resilient to stress.

To assess whether people might respond similarly to ezogabine, investigators at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York and Baylor College of Medicine in Houston recruited 45 adults with a depressive disorder that included clinically significant levels of anhedonia for a trial. The participants were randomly assigned to either daily ezogabine (up to 900 mg/day) or placebo for five weeks.

In addition to monitoring the participants’ depression and anhedonia over the course of the trial, the investigators assessed whether ezogabine altered brain activity in the ventral striatum—a control center for reward and pleasure. The participants were asked to complete a guessing task for a chance to win money while receiving an MRI; scans were conducted at the beginning and end of the trial.

Lead study investigator James Murrough, M.D., Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at Mount Sinai, told Psychiatric News that the neuroimaging data were included to follow the National Institute of Mental Health’s (NIMH) vision for mechanism-based clinical trials—that is, trials that not only demonstrate a medication is effective, but also can explain why it is effective.

“It is also an attempt at finding a transdiagnostic intervention,” Murrough said. “Focusing on a core symptom of mental illness like anhedonia that is found in many disorders opens up more clinical opportunities than focusing on a discrete diagnostic condition.”

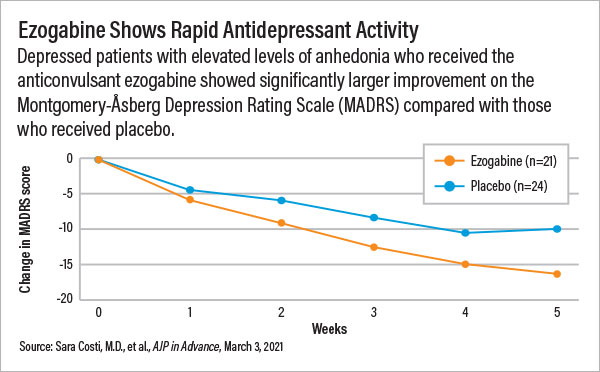

The patients who received ezogabine reported significantly lower scores on both the depression and anhedonia scales relative to placebo users after five weeks, with a clear difference between the two groups emerging after just two weeks. The patients rapidly improved even though the ezogabine dose was raised slowly to minimize the risk of dizziness. (Participants did not reach the target 900 mg/day dose until week 4.)

“Based on the standard clinical trial metrics like symptom severity, this medication did great,” Murrough said. “There are even some signs that ezogabine might have rapid antidepressant and anti-anhedonia effects. If we could titrate the dose more rapidly, we might be able to see improvements in one week or even less.”

The objective MRI data were not as clear-cut as the clinical findings, Murrough said. Though the participants taking ezogabine showed elevated activity in the ventral striatum after five weeks compared with participants taking placebo, the differences were not statistically significant.

“The data indicate that there is very likely something going on in this region following ezogabine exposure. We might have been able to show it definitively with a different tool or even with just a few more participants,” Murrough said. “But based on the parameters we set at the onset of the trial, ezogabine did not meet our primary goal.”

Alan Schatzberg, M.D., the Kenneth Norris Professor of Psychiatry at Stanford University and former APA president, said that the disparate clinical and imaging data from this study highlight the challenges of designing drug studies that need to prove that the drugs engage specific biological targets and provide clinical benefit. He noted that NIMH’s motivations to include “target engagement” in smaller studies are valid given that so many drugs that show promise at first then fizzle out in larger and more expensive trials. But as he explained in an editorial accompanying this study, “Undue emphasis on the target validation rather than on determining clinical effects is perhaps as likely to delay drug development as it is to facilitate it.”

This study was supported by grants from NIMH and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, with additional support from the Ehrenkranz Laboratory for Human Resilience at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. ■

“Impact of the KCNQ2/3 Channel Opener Ezogabine on Reward Circuit Activity and Clinical Symptoms in Depression: Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial” is posted here.