Amyloid-Busting Antibody Wins FDA Approval, but Courts Controversy

Abstract

The FDA gave a conditional green light to aducanumab on the basis that the medication that reduces the size of amyloid plaques will slow cognitive decline—a connection not yet established in research.

Normally, news that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had approved the first new treatment for a severe and debilitating disorder in nearly 20 years would be cause for celebration. But ever since the FDA announced in June that the agency had approved the monoclonal antibody aducanumab to treat Alzheimer’s disease, controversy has surrounded the treatment.

The mixed response to aducanumab (developed by Biogen under the brand name Aduhelm) is due in part to how the medication was approved via the FDA’s accelerated approval pathway. This pathway is designed to speed up the approval of medications for serious or life-threatening illnesses by allowing companies to provide a surrogate endpoint that reasonably predicts future clinical benefit. For example, companies developing cancer treatments often use tumor shrinkage as an endpoint rather than long-term survival rate to enable clinical trials to be completed quickly. As part of an accelerated approval, the company must conduct a postmarket clinical trial to prove the clinical efficacy of the approved medication; if that trial fails, the FDA may initiate proceedings to withdraw its approval.

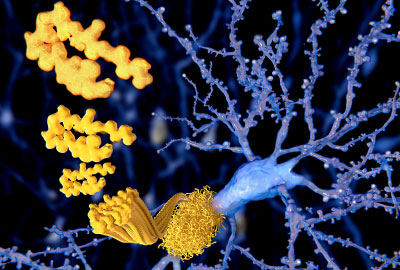

In the case of aducanumab, the surrogate endpoint was evidence that people who took the medication had significantly greater reduction of amyloid beta plaques in their brains after 78 weeks than those who took placebo. Alzheimer’s disease is frequently characterized by pathological changes in the brain including amyloid beta plaques and neurofibrillary, or tau, tangles.

The problem, as many experts in the field have argued, is amyloid plaques are a poor biomarker for Alzheimer’s; there is scant evidence that amyloid causes any of the cognitive and behavioral symptoms of the disease.

“I’ve argued for over 20 years that amyloid accumulation is a response, and potentially a protective response, to this disorder,” said George Perry, Ph.D., the Semmes Foundation Distinguished University Chair in Neurobiology at the University of Texas at San Antonio and a leading researcher of amyloid pathology.

Perry, who is also editor in chief of the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, hypothesizes that amyloid accumulation is a response to increased oxidative stress in aging brains. “Disrupting this process could even have negative implications in many patients,” he cautioned.

Kostas Lyketsos, M.D., the Elizabeth Plank Althouse Professor for Alzheimer’s Research at Johns Hopkins Medicine and chair of psychiatry at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, had similar concerns about using amyloid levels as a proxy for cognitive health. “If there was at least some clear evidence of clinical benefit, it might be easier to accept this decision, but from what we know, at best this medication just prolongs the duration of symptoms,” he said.

Phase 3 Trials Leave Questions Unanswered

The clinical data at the heart of the FDA approval comes from two phase 3 trials launched in 2015 by Biogen: ENGAGE and EMERGE. Both trials compared the effects of low-dose (6 mg/kg) or high-dose (10 mg/kg) aducanumab—given intravenously each month—with placebo in patients with early stage Alzheimer’s disease and an amyloid-positive brain scan.

There were high expectations for ENGAGE and EMERGE, after Biogen’s phase 1b study showed promising clinical and imaging results. In March 2019, however, both ENGAGE and EMERGE were halted when an analysis of interim data showed neither dose of aducanumab was likely to be superior to placebo at slowing cognitive decline.

A few months later, Biogen reported that additional analysis of the data had revealed that the drug demonstrated a benefit over placebo. When including all data up to March 2019 (the interim analysis included data up to December 2018), the researchers found that patients in the EMERGE trial who received high-dose aducanumab exhibited modestly slower cognitive decline than those in the placebo group. In contrast, analysis of data collected as part of the ENGAGE study showed that patients who received high-dose aducanumab experienced similar cognitive decline as those who received placebo, Biogen reported.

In December 2019, Biogen announced that further analysis of the ENGAGE data revealed that patients who received the full treatment of 14 monthly infusions of high-dose aducanumab had slower cognitive decline than those who received placebo. Based on this revised analysis, Biogen decided to move forward with seeking FDA approval for the 10 mg/kg dose of aducanumab.

The FDA advisory panel that reviewed the data was not impressed. They voted nearly unanimously in November 2020 that the clinical data supporting aducanumab were not sufficient to warrant approval. The FDA rarely overrides the advisory panel.

“The most compelling argument for approval was the unmet need, but that cannot, or should not, trump regulatory standards,” Caleb Alexander, M.D., a professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University and member of the FDA advisory panel, told STAT. Shortly after the announcement, three members of the panel quit the FDA panel in protest of the controversial decision.

Aducanumab Comes With Risks

The approval caused concern over more than just the dubious evidence of benefit, Lysetkos said. Though aducanumab was well tolerated overall in the study, the drug does have risky side effects, particularly a condition known as ARIA, or amyloid-related imaging abnormalities. ARIA involves temporary internal swelling or bleeding that can arise when amyloid plaques are removed. Often ARIA present with no visible symptoms but some patients experience headaches, confusion, tremors, blurred vision, and falls.

Although the ENGAGE and EMERGE trials only enrolled adults who had early stage Alzheimer’s, the FDA originally did not limit approval to only this subgroup of patients. In July—following blowback from physicians and patient advocates—the aducanumab label was updated to read “treatment with Aduhelm should be initiated in patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which treatment was initiated in clinical trials.”

The label update does not prohibit aducanumab’s use in other patients, including those with more advanced Alzheimer’s, nor does it restrict use due to other medical issues. (For example, adults with a recent history of heart disease or stroke were excluded from the clinical trials.)

“We may potentially expose hundreds of thousands of people to this drug, including many elderly and frail people,” Lysetkos noted. “I fear there could be many unnecessary deaths.”

Factor in the staggering cost of aducanumab (estimated at $56,000 for a year of infusions) as well as the high costs of accompanying brain scans to confirm the presence of amyloid buildup and monitor for potential ARIA, and one can see why many specialists were concerned with this approval. “I would not recommend this to any patient given what we know right now,” said Perry. “This drug has borderline efficacy, staggering costs, and potentially fatal side effects. Aricept [donepezil] is a far better choice; it also just barely works but is inexpensive and safer.”

What Will Approval Mean for Research?

Some researchers are more optimistic about what the approval might mean for Alzheimer’s patients and research. Malaz Boustani, M.D., M.P.H., the Richard M. Fairbanks Chair of Aging Research at Indiana University School of Medicine and a research scientist at the Regenstrief Institute, told Psychiatric News that aducanumab’s approval, while not ideal, was appropriate under the circumstances. Despite the ARIA risks, aducanumab has a better safety profile than other antibody-based infusions that are commonly used in chemotherapy, and Alzheimer’s—like cancer—is a tremendous burden on the health care system.

“I have some personal bias [Boustani’s father was recently diagnosed with Alzheimer’s], but how many millions of people have to die while we wait for the perfect clinical solution?” he asked.

Boustani added that the approval could also have a ripple effect in improving the recognition of Alzheimer’s. “Currently, we miss anywhere from 50% to 80% of patients with Alzheimer’s because brain scans are not routinely provided as a standard of care.”

Now that a potential treatment exists, physicians may be more willing to recommend brain scans for patients who have demonstrated amyloid build up. Even if the scans do not identify amyloid, they may uncover other problems, such as vascular damage, which can provide more insight into the type of neurodegeneration a patient is experiencing.

“This approval could be the first step toward more personalized dementia care,” he said.

Perry noted that aducanumab’s approval might open up other opportunities in drug development. “Companies have been chasing this amyloid hypothesis for over 30 years. Now that a drug finally got approved, maybe there will be more money for other areas of research,” he said. “I’m not convinced it will happen, but we’ll see.”

In the meantime, physicians such as Lyketsos are bracing for the impact now that aducanumab is commercially available (Biogen began shipping out the medication at the end of June). While some institutions like the Cleveland Clinic stated publicly they would not prescribe the drug, Lyketsos noted that he and others at Hopkins are open to offering the medication to patients, but in a manner that is conservative (only given to patients with very mild symptoms who have amyloid in their brains), careful (systematic monitoring for any side effects and clinical worsening), and transparent (upfront with patients on what this medication can and cannot offer).

“Whatever we think, this medication is out there, and many patients and families will want it,” he said. “The best we can do now is manage its use appropriately.” ■