Special Report: Psychiatric Management of BPD—Helping Young Patients, Psychiatrists, and Families Work Together

Abstract

Good Psychiatric Management for Adolescents emphasizes improving patients’ functioning with borderline personality disorder (BPD) while controlling their symptoms. The goal is to balance clinical care with life goals rather than create a split between living and receiving care.

Growing up is hard to do and is getting harder all the time. Social mobility, freedom of self-expression, and growing diversity have given greater options to young people to choose and act on who they want to be or identify as in this modern era. These same progressive forces create overwhelming decisions that take a lifetime to sort out to form a coherent identity.

The mental health of teens is constantly under pressure. The pandemic of isolation during COVID-19 multiplies this pressure. Digital tools for rendering the self publicly mean young people can make friends around the world. It also means they can be bullied or preyed on in anonymous hate crimes where there are no consequences or protective safeguards. Suicidality, self-harm, and other forms of traumatizing adversity continue to evade adequate solutions by any profession or community. Teens need help to grow up in a way that promotes mental health more than ever.

The Handbook of Good Psychiatric Management for Adolescents With Borderline Personality Disorder is a guide for psychiatrists and mental health professionals to help young people figure out how to manage themselves and their relationships. Personality disorder arises when disturbances of the self—related to identity, self-esteem, and coping with emotion and thoughts—combine with difficulties developing reliable, stable relationships. The gold-standard treatments for personality disorders are psychosocial interventions that promote socioemotional capacities to stabilize personality functioning. These are skills that people with borderline personality disorder (BPD) especially need. The side-effect profile of these interventions is benign.

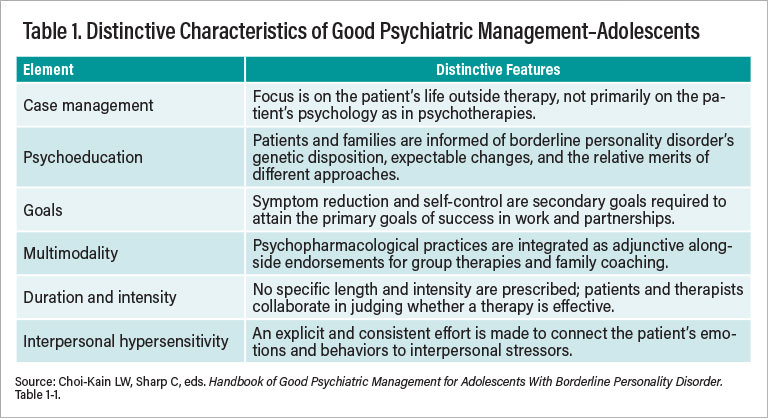

Good Psychiatric Management (GPM) is a commonsense clinical management approach to treating patients with BPD. The largest randomized, controlled outpatient psychotherapy trial to date on dialectical behavior therapy found that GPM achieved similar positive outcomes in terms of self-destructive behavior, interpersonal functioning, depression, anxiety, and functioning despite its relatively less-intensive format. Incorporating ingredients that all health professionals use to manage patient care—such as diagnostic disclosure, psychoeducation, goal settings, management of safety and comorbidities, and conservative prescribing—GPM can be used in any psychiatric setting as well as primary care settings (see Table 1).

We adapted GPM for adolescents (GPM-A) to promote earlier intervention. BPD is an outcome, not just a starting point. As prevalent in adolescence as it is in adults, BPD develops when those who are emotionally, interpersonally, and stress sensitive endure unmanageable adversities without adequate support. Adolescence is a sensitive and crucial developmental phase. Teens explore independence and maneuver through social worlds that can be fraught with danger before their brains are fully developed. At this stage, young people possess both vulnerability and potency in the face of the many exposures to opportunity and risk they encounter day to day. They need help, but such help must be different from the kind to which they were accustomed as a child. Developing the skills of thinking first before acting, discovering what they are good at and not good at, and building a healthy sense of self through corrective experiences require partnering with a trusted source of objectivity and wisdom who does not cramp their independent strivings too much. Parents and/or other nonphysician adults close to adolescents can provide that sort of counsel. Psychiatrists can help parents in this endeavor when their child shows signs of mental illness.

Why Do Clinicians Hesitate to Diagnose BPD?

Early intervention is always good medicine regardless of diagnosis. It enables preventative and noninvasive measures prior to progression of more permanent and disabling symptoms that can lead to poor health outcomes. GPM medicalizes BPD as a disorder that is common, easily understood, and responsive to treatment with a largely good prognosis, especially when detected and treated early.

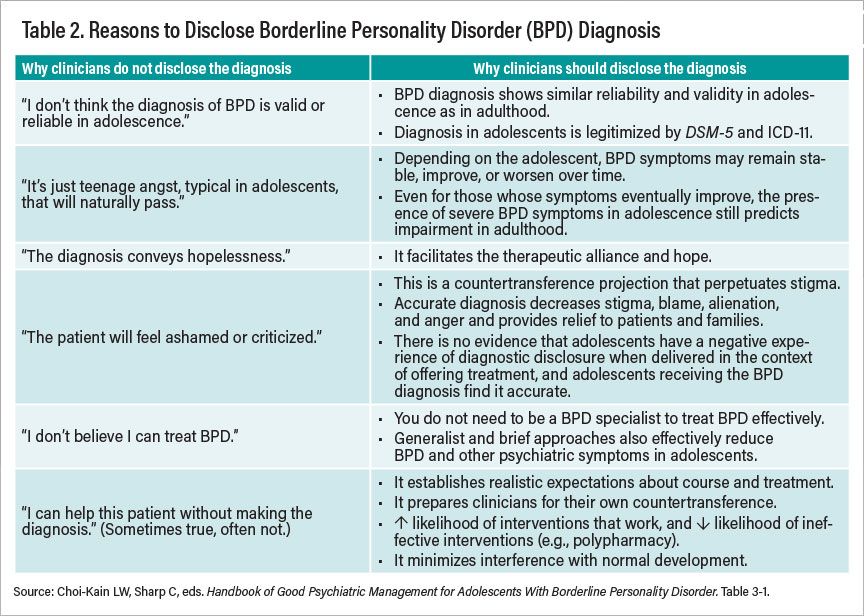

Many clinicians have not heard that a valid BPD diagnosis can be made reliably in adolescents. Others believe that BPD symptoms are just normal for teenagers. Often, clinicians feel the diagnosis conveys hopelessness.

Stigma, misinformation, misunderstandings, and lack of access to specialized care breed reluctance to diagnose BPD, especially early in the young patient’s life. However, there are no other medical conditions for which health care professionals commonly avoid a diagnosis because of how they think the patient may react. Mental health professionals are not given the training or tools to make the diagnosis with confidence and competence (see Table 2).

GPM-A seeks to solve this dearth of generalizable clinical resources for BPD by making its contents and procedures user friendly and down to earth. It is good enough, as Donald Winnicott noted, to usher forward steady growth and independence. For youth who fail to respond adequately, more intensive specialized resources may be used if they are available.

The GPM-A Approach

Good psychiatric management of any disorder starts with diagnosis. It clearly describes the problem that the clinician and patient will work on managing and resolving together. This framework incorporates collaborative roles and goals within the therapeutic relationship that can anchor the predictable storms that unfold for patients with BPD as well as their family members.

When BPD is diagnosed, these relational conflicts are the problem that treatment aims to address, rather than a product of a “bad” patient, family, or clinical team. GPM-A advises clinicians to identify BPD’s symptoms early, as they develop, rather than after they fully emerge. When a patient’s blood pressure is assessed, the patient is told the range of normal findings and is warned when the measurement approaches hypertensive levels. Clinicians can and should disclose emerging symptoms and discuss a differential diagnosis in the face of uncertainty. This is not specific to BPD care, but simply good clinical management.

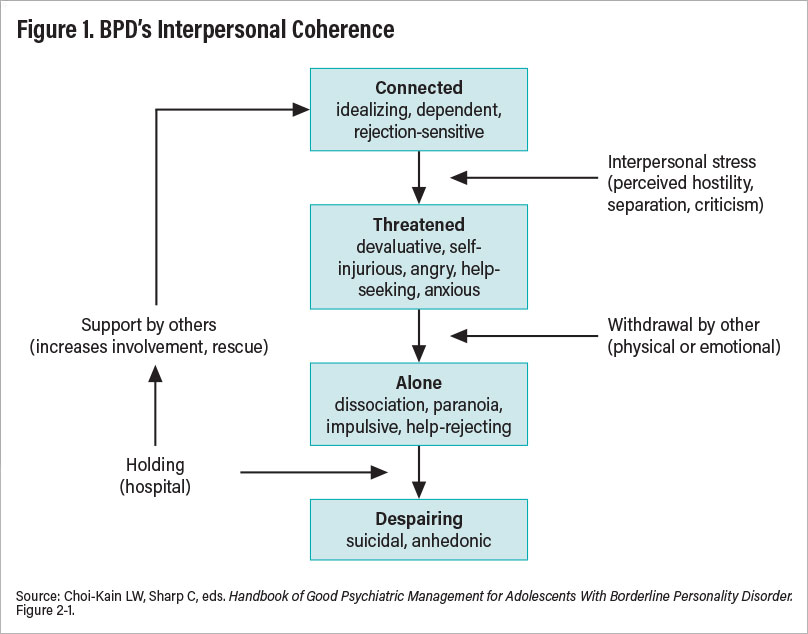

The GPM-A handbook provides tools to reliably review diagnostic features of BPD in a way that educates patients and their families. As a result of this education, patients and families can anticipate when patients will become destabilized and know how and when to intervene. John Gunderson famously coined BPD as a problem related to intolerance of aloneness, which he observed as a core engine behind the symptomatic oscillations of his patients. This formulation of BPD is depicted in Figure 1, which can be shared with patients, families, school liaisons, and other significant people in the patient’s life.

According to GPM-A’s “interpersonal coherence model,” young people with BPD may appear relatively steady, positive, and receptive to direction and collaboration when they are feeling connected to others. The problem is that they remain sensitive to rejection and dependent in a way that causes them to be prone to real or perceived threats to relationships. When these threats, such as criticism, separation, and disagreement, inevitably occur, these teens enter a more volatile state in which they express anger either toward themselves in the form of deliberate self-harm or toward others in aggressive hostile behavior. The problem for these interpersonally sensitive young people is that such behavior alienates others and causes real abandonment, leading to the teens’ descent into a more acute, difficult-to-reach state of being dissociated, paranoid, and impulsive in more reckless ways. When truly alone, feeling worthless and hopeless in the absence of the care of others, teens with BPD are more seriously suicidal. Those around them may intervene, reconstituting social support and contact and returning them to a connected and more stable state. In the short run, this intervention by concerned others reconstitutes the teens with BPD by re-establishing social connection and a sense that they matter because others care. The problem is that in the long run, this cycle reinforces helpless and self-destructive behaviors as a means of gaining support. Fluctuating between states of dependency, hostility, and need for rescue begins to define young people’s interpersonal style.

Case Example of GPM-A

Olivia, who is 15 years old, was referred to Dr. G in the child psychiatry department by her pediatrician after he observed multiple cuts on her arms and legs. Olivia’s parents, Rose and Martin, told the psychiatrist that Olivia has always been a sensitive child who performed well in school but struggled to maintain a stable group of friends. Rose expressed fears that Olivia would kill herself, but Olivia had not expressed suicidal ideation and had no history of suicide attempts. Rose wanted her to be hospitalized immediately as she preferred “being safe to being sorry,” but Martin felt that she was overreacting to normal teenage behavior.

When Dr. G spoke with Olivia alone, he asked her what was happening in her life at school and home. As Olivia described her recent falling out with her best friend, Dr. G expressed his curiosity about whether the understandable social stress of this situation had anything to do with her self-harm. Olivia explained that she noticed that she had a pattern of having one best friend at a time and relied so heavily on these exclusive relationships that over time, she felt like a burden. Olivia said, “I guess I can’t do anything right, and everyone hates me.” Dr. G expressed his interest and replied, “That sounds like a terrible situation for you. I agree we need to think of better ways of managing these moments so that when you feel threatened, you can cope in a way that does not end your friendships.”

Olivia started to become more engaged and showed interest when Dr. G explained Good Psychiatric Management’s interpersonal hypersensitivity model. She felt that it described her accurately. Dr. G explained that these are symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD), a common condition that often arises during adolescence when social and academic demands increase as support from adults tends to decrease. Together, Olivia and Dr. G explained the BPD diagnosis and the interpersonal hypersensitivity model to her parents, who recognized the patterns they described immediately. Dr. G explained that there are many treatments that work for BPD and that generally its symptoms, particularly self-harm, diminish in the majority of cases over time. Rose and Martin were given psychoeducation about the disorder and the Borderline Personality Disorder Family Guidelines, relieving their confusion.

After this initial psychoeducation, when Olivia harmed herself, Rose and Martin were now less anxious and irritated. They learned to show interest instead and lean in when she was distressed and angry. Over time, Olivia was able to talk to them about her problems with friends at school. Together, Olivia, Rose, and Martin worked with Dr. G to find more effective ways to meet Olivia’s needs without harming herself. She joined the school choral group and developed a larger group of friends. By the end of her freshman year, Olivia had a stable social circle; felt closer to her parents, who came to understand her better; and stopped cutting herself. While she remained anxious and sensitive, she felt more confident in her ability to manage her problems and accept support from her parents.

By explaining these tendencies to youth with emerging BPD symptoms, clinicians who use GPM-A empower them to be more aware of these signs and think first about what they can do to gain the social support they want and need. Encouragement of prosocial behaviors such as asking for help or controlling anger stabilizes teens’ ability to manage themselves as well as their relationships. In so doing, a more positive sense of self can be fostered as hostile interchanges are reduced and collaborative communication is increased. In this way, GPM-A strengthens processes that teens who are less interpersonally sensitive may naturally learn.

Moving on to Live Life and Forming Compromises

After clarifying the symptoms of BPD and the interpersonal coherence model, GPM-A instructs clinicians and patients to focus on life outside treatment. The job of teenagers is to go to school to learn how to learn and find out what they like, what they are good at, and where they can belong. This knowledge paves the way for future opportunities, self-direction, and identity. When teens with mental health problems leave these usual arenas of development, they fall behind and become even more isolated from peers, compounding the detriments of their vulnerabilities. It is this separation and growing deficits in skills and experience that disable teens with major mental illness over time.

For this reason, GPM-A emphasizes function alongside symptom control as a priority. Patients should be expected to become symptomatic under stress. The clinical goal may not always be to eradicate symptoms completely, but rather to manage symptoms while pursuing life goals to the best of the young person’s abilities. At times, symptom relief comes at the price of avoiding stressful demands by seeking safety and asylum in hospitals or with polypharmacy. GPM-A reminds clinicians this is a short-term solution that allows preparation for resuming life responsibilities. Hospitalization or other long-term forms of care provide time to slow down so young patients can make realistic adjustments and plans for how to cope better.

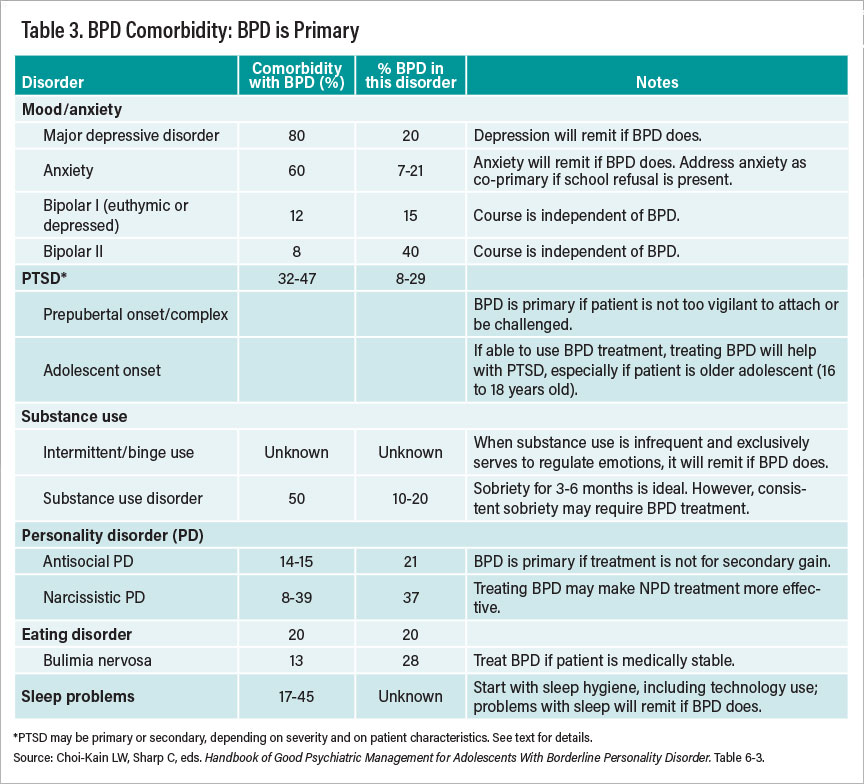

We know that those who develop BPD symptoms in their younger years are at risk for developing other psychiatric disorders. GPM-A advises clinicians about how they can prioritize different diagnoses based on high-quality longitudinal studies of both children and adults that have informed us which disorders impact the course of other disorders. BPD aggravates the course of most mood, anxiety, and behavioral disorders and renders their treatments less effective or more challenging (see Table 3).

Understanding self-harm and suicidality in the context of life difficulties is a major task within the GPM-A framework. Using standard psychiatric assessment of suicide risk and safety planning, the GPM-A handbook provides a guide to navigating the decisions clinicians and families need to make about level of care. Patients, families, and clinicians work together to address acute safety concerns with the ultimate goal of making patients feel that life is worth living. Management of safety concerns must help teens depart from treatment settings for as long as possible, perhaps for stretches at a time. These breaks are normal when possible. The ultimate goal is that patients leave treatment with the purpose of pursuing fulfilling activities with fewer stumbles and falls. Treatment will always be available if needed.

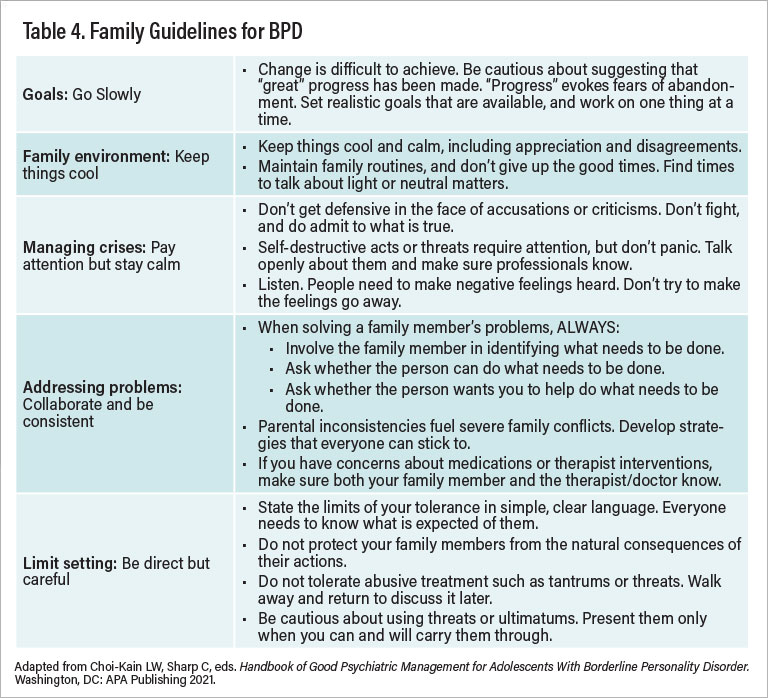

Through this all, families need specific guidance. We outline commonsense tips that nearly anyone in the teen’s interpersonal orbit can use (see Table 4).

Informed by extensive review of the treatment literature, GPM-A also outlines an algorithm for conservative psychopharmacology, which places collaborative responsibility on patients and clinicians to track symptoms, treatment response, and side effects. The collaboration between patients and clinicians fosters joint responsibility and a mutuality that relies on teens to make their own decisions about how to take care of themselves. A related aim is for teens to influence grown-ups to trust them more with increasing evidence that they can in fact do so credibly most of the time, learning when they need help when mistakes happen.

A major goal of GPM-A is to preserve the young person’s path to a life outside of being a patient as much as possible. GPM-A instructs us to keep treatment as nonintensive as possible and in a way that does not disrupt other activities. Informed assessment of risk, safety management, and addressing self-harm and suicidality are critical in this endeavor.

Conclusion

GPM-A is a flexible and pragmatic approach that is used as needed. As a primary care approach, GPM-A advises routine checkups, with more frequent appointments prescribed when need arises and then tapered when discrete flare-ups subside. GPM-A outlines how others can productively respond so that the environment fosters growth rather than reinforcing BPD’s oscillations. As John Gunderson said in writing his original handbook on GPM: “I do not see myself as particularly gifted, and I do not believe that only experts can be effective treaters. I do believe that I have become ‘good enough’ for most patients [with BPD], and that if I can do this work, then so can most others.”

With my co-editor Carla Sharp and the handbook’s co-authors, we hope you will feel the same. It takes a village to raise a child, and we in the psychiatric profession must work together with patients and their families to help these young people improve their mental health and grow into more independent and successful adults. ■