Special Report: Gambling Disorder Not Uncommon but Often Goes Undiagnosed

Abstract

With rates of gambling-related suicide attempts somewhere between 12% and 30%, psychiatrists need to be prepared to diagnose, treat, and—most important of all—understand their patients with this illness.

“I feel completely out of control. Why am I doing this?”

Antoine was a 34-year-old, married man with two young children in school. Like many people, Antoine had always enjoyed betting on sports games with friends for a few dollars over the years. It had never caused him any difficulties. A couple of years ago, however, he lost his job in an accounting firm due to downsizing and was home most of every day. That was when he began betting on sports online. He was amazed at how many games he could bet on at one time. Although it had started out episodically and with small wagers over a period of a few months, Antoine was betting on dozens of sporting matches every day, even sports about which he admittedly knew little, and his behavior had escalated into larger and larger wagers.

“I became obsessed with betting” was how he described his behavior. Not making any income, he went through thousands of dollars of savings and accumulated fairly large debt on multiple credit cards. Antoine’s wife asked about his job search daily, and he began lying to her, making up elaborate stories of interviews. In fact, he had not applied for any positions since he had begun gambling. He also lied to her about paying the credit card bills, and they sank deeper and deeper into debt. Every evening he disparaged himself for his behavior, telling himself he was out of control and promising he would quit gambling and look for a job the next day. Upon awakening each morning, however, he would head to his computer and begin gambling again, often trying to win back what he had lost the day before. He also began ignoring his children when they returned from school as he was in his study “looking for work” but was in fact gambling. After his wife found out by chance that they were seven months behind on the mortgage and she confronted him, Antoine admitted his behavior and sought treatment.

Whether it is having a poker night with friends, participating in an office March Madness pool, or buying a lottery ticket, most Americans have gambled at some point in their lives. When done responsibly, gambling can be fun, thrilling, and potentially rewarding; hiding in plain sight, however, are millions of people struggling with gambling disorder.

Gambling has also changed over the years, and psychiatrists need to be aware of the myriad ways that people gamble today. Not confined to land-based casinos or bars where people can buy pull tabs (tickets with tabs that can be pulled off to reveal what is hoped to be a winning combination of symbols), gambling has partnered with technology in complex ways to make gambling available to almost everyone at all times of the day and night. For example, the gambling-gaming convergence has exposed children and adolescents to the world of gambling via games in which people win money and then use their winnings to further their gaming. This has in turn led many parents to seek treatment for their children for gaming problems only to find that the underlying issue is often a gambling disorder. This gambling-gaming interface has also resulted in younger and younger people seeking help for gambling disorder. For adults, the growth of interactive gambling platforms, role of new player experiences and reward structures, tailoring of products to individuals, and integration of gambling into other online activities, such as social media, means that many people develop a gambling disorder quickly and may even be unaware that they are actually gambling: Because these games are online, many people have told me that they thought it was simply a fun game that got horribly out of control.

Approximately 1% of the U.S. population has gambling disorder, which puts this condition on par with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in terms of prevalence. Yet compared with those two disorders, most people who have gambling disorder do so without showing any clear signs to their loved ones or physicians. Unlike substance use disorders, patients with gambling disorder frequently do not present any clear physiological signs of intoxication or withdrawal. Men seem to struggle with gambling disorder at higher rates than women, and yet women are far more likely to seek treatment for gambling problems. Rates of gambling-related suicide attempts are somewhere between 12% and 30%, and so gambling disorder is arguably as serious as many other illnesses encountered by psychiatrists.

Diagnosing Gambling Disorder

Psychiatrists should familiarize themselves with the DSM-5-TR criteria for gambling disorder. Though the criteria largely mirror those for substance use disorders, the most frequently endorsed criterion for gambling disorder is a distinct symptom known as “chasing losses”—the tendency to try to quickly win back lost money, which can lead people to make progressively larger and more reckless bets.

For busy clinicians, there is a range of short and long questionnaires and self-report measures to assess whether an individual has gambling disorder. One of the most used and reliable screens is the Lie/Bet Questionnaire, which consists of just two questions: Have you ever had to lie to people important to you about how much you gambled? Have you ever felt the need to bet more and more money?

Screening is important as people with gambling disorder are loathe to discuss their gambling habits unprompted, often feeling they do not have a medical or psychiatric problem but rather a character flaw. Additionally, because gambling disorder may present at any time from adolescence to older age, almost everyone should be screened.

For patients with a positive screen for gambling disorder, psychiatrists need to assess the extent of the problem, not just in terms of gambling symptoms and the amount of time spent gambling but also the effects of gambling on the individual’s life, and evaluate for risk of suicidality.

Gambling can have profound negative consequences on a person’s health (it is associated with hypertension); family life, finances, and work life (marital discord, bankruptcy, and workplace absenteeism are common); social life (people with gambling disorder often isolate from friends); and overall well-being (legal issues associated with gambling can wreak havoc on quality of life). For adolescents or young adults who have a gambling disorder, the financial and work consequences may not be as much of a problem if they are in school, not working, and parents are supporting them. In fact, one university student with gambling disorder told me that he simply asked his parents for more money each month and so he denied any financial issues due to gambling. Adolescents and young adults, however, may instead report that the largest negative consequences of their gambling is in the area of relationship stress (for example, not spending time with friends, losing relationships due to gambling) and school performance. In the case of older adults who have a gambling problem, the financial effects can be even more devastating due to their having to live on a fixed income. People with gambling disorder often require referrals to general practitioners and financial advisors and may need couples therapy and even legal counseling.

Part of the overall health assessment should include asking patients about the medications they have been prescribed and are taking. Starting about 20 years ago, people noticed that certain medications, especially dopaminergic drugs such as those for Parkinson’s disease and the antipsychotic medication aripiprazole, seemed to be associated with the onset of gambling problems. DSM-5-TR even included in the diagnostic criteria that people who gamble only while using dopaminergic agents should not receive the diagnosis of gambling disorder. Similarly, gambling disorder should be ruled out for people who engage in reckless gambling during a manic cycle of bipolar disorder.

Psychiatric Comorbidities Common

Table 1

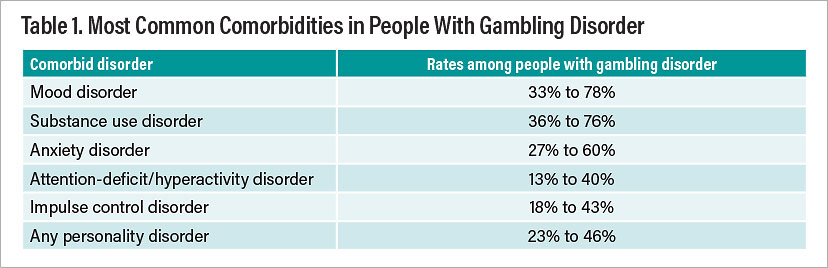

Before treatment planning can commence, psychiatrists need to determine whether the patient has another psychiatric disorder, which is more the rule than the exception. The most common co-occurring psychiatric disorders include mood disorders (depression), substance use disorders (particularly alcohol use disorder and nicotine dependence), and anxiety disorders (Table 1).

Addressing comorbidity is complex for this patient population. For example, if the patient has depression and anxiety, does the depression or anxiety drive the gambling behavior—that is, does the person feels exhilarated or calm only while gambling? Or does the gambling lead to depression and anxiety? Knowing which is the driving force may result in very different treatment plans.

Psychiatrists should not assume that the co-occurring condition is more important than the gambling disorder. In my experience, patients are often told that their behavior is a consequence of their depression and psychiatrists do not probe the gambling behavior to any extent. This is probably due to the fact that psychiatrists often do not feel comfortable with how best to treat patients with gambling disorder and so opt for a problem with which they are familiar.

Of course, sometimes these factors are only sorted out after multiple meetings with patients. When in doubt, psychiatrists should have a working hypothesis but be willing to change approaches when the initial plan is not helping.

Treatment Approaches

The neurobiology of gambling disorder is far from completely understood, but the findings to date suggest that many people with gambling disorder exhibit a similar reward-processing dysfunction as seen with substance use disorder, which is why gambling disorder was included in the substance use disorders category of DSM-5-TR and why many successful treatments for gambling disorder are in part borrowed from those used for substance use disorders. Research on circuit-based treatments, predictors of treatment response, and long-term prognosis are ongoing.

Even without a clear understanding of the neurobiology of gambling disorder, interventions of varying intensity have been developed and proven effective. Lower intensity interventions (for example, self-guided interventions such as workbooks or brief professional interventions such as motivational interviewing) may be a place to start, moving on to more intensive interventions such as weekly cognitive-behavioral therapy (individual or group formats) or even inpatient residential programs.

The “gold standard” of care is cognitive-behavioral therapy; it is the best studied treatment for gambling disorder and has produced the most robust outcomes. It is therefore crucial for clinicians who treat gambling disorder to be trained in providing evidence-based care.

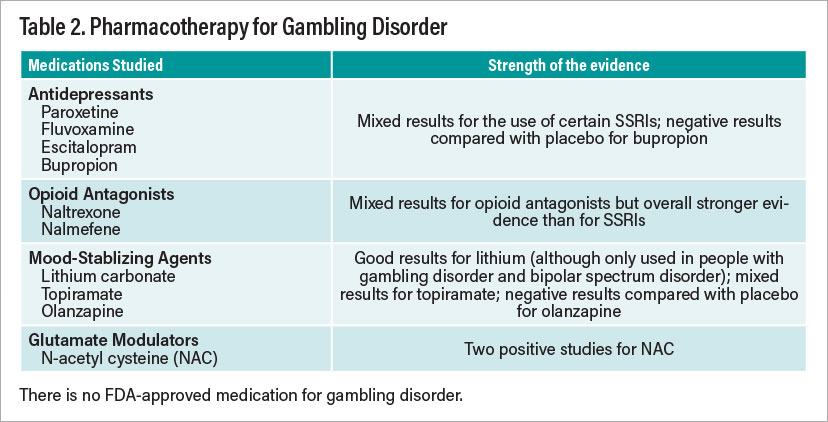

In addition to psychotherapy, psychiatrists should also consider the use of adjunctive medication—with the caveat that there are no FDA-approved medications for gambling disorder. Although several classes of medication have shown efficacy in treating people with gambling disorder, we lack large multicenter studies supporting the use of medications.

Table 2

Nevertheless, the opioid antagonist naltrexone (currently FDA approved for alcohol and opioid use disorders) and the nutraceutical N-acetyl cysteine (a glutamate modulator) seem to have the strongest evidence for their use in treating gambling disorder (Table 2). Naltrexone may be particularly useful for patients who have strong urges to gamble or have a family history of addictions. The choice of medication, however, may also be influenced by which comorbidities are involved. For example, naltrexone may be a wise first choice for patients with gambling disorder and alcohol use disorder, whereas a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor may be a good option for patients with gambling disorder and severe major depressive disorder.

In addition to professional interventions, other approaches, often used as augmentation to psychotherapy, are available. The most popular is Gamblers Anonymous (GA), which is available around the world and mirrors the 12-step approach of Alcoholics Anonymous. GA provides moral, social, and practical support in a group format. Although many gamblers fail to attend more than a single session of GA, those who have high attendance and engagement appear to achieve abstinence.

Another potentially useful supplement to treatment is voluntary exclusion. Casinos, card clubs, and internet gambling sites allow patrons to place themselves voluntarily on a “Do Not Serve” list for varying periods of time. People on the list who try to enter an excluded establishment are removed and potentially charged with a trespassing offense. When used with individual psychotherapy, voluntary exclusion may provide additional benefit.

Conclusion

Treatment for gambling disorder has evolved over the past 30 years, and there are many evidence-based interventions. It is a worldwide problem, and research continues to develop more effective treatments. That does not mean, however, that people take advantage of current treatments.

If we return to the case of Antoine, it should not surprise anyone to learn that he came to an initial appointment and made strong pronouncements that he wanted to quit gambling. Despite these statements, he failed to follow up with treatment initially. Patients’ ambivalence about treatment is strong, as many people want to quit losing at gambling more than they want to quit gambling. Even with evidence-based interventions, people with gambling disorder struggle, oftentimes with multiple relapses and feeling hopeless about getting better. Approximately six months after his initial appointment, Antoine re-entered treatment as his marriage was on the point of collapse, and this time he stayed in treatment receiving both therapy and medication.

New technologies, the rise of internet gambling, and other money-chasing trends like cryptocurrencies are expanding gambling opportunities and bombarding people with these options. Will the rates of gambling disorder increase with more and easier opportunities to gamble? Because of this concern, public health initiatives need to focus on primary prevention through educating people of all ages about the risks associated with gambling. Because of the ubiquity of gambling, people who already have a problem may develop a worse gambling problem, and those who are trying to stop may face multiple hurdles to achieving abstinence. To combat the barrage of gambling opportunities, psychiatrists and researchers need to continue to develop better treatment options that recognize the ambivalence of gamblers (such as Antoine) to quit and the various demographic differences (for example, gender, age, race/ethnicity) of people with gambling disorder. ■

Disclosure statement: Jon E. Grant, M.D., M.P.H., J.D., has received research grants from Otsuka and Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. He receives yearly compensation from Springer Publishing for serving as editor in chief of the Journal of Gambling Studies and has received royalties from Oxford University Press, APA Publishing, Norton Press, and McGraw Hill.