Women in Academic Medicine Still Paid Less Than Men

Abstract

Psychiatry is one of the medical specialties in which salary gaps between women and men persist.

In 1849 Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman in the United States to earn a medical degree—and 173 years later, women in academic medicine are still paid less than their male peers for doing the same work. A study in JAMA Network Open has found that women in academic medicine have lower starting salaries than men in the vast majority of medical specialties, including psychiatry, and that this salary disparity has repercussions on women’s earning potential that extend long into their careers.

“The focus needs to shift from raising awareness of gender-based pay disparities to developing programs that actually address them.” —Eva Catenaccio, M.D.

“These disparities, which can total hundreds of thousands of dollars over the first 10 years of a career, are largely the result of gender-based differences in annual salary that start immediately after training,” lead author Eva Catenaccio, M.D., an epilepsy fellow at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told Psychiatric News. “We weren’t necessarily surprised that gender disparities in earning potential exist—that’s been well documented—but the ubiquity of the disparities as well as the fact that they start immediately after training, when in theory female and male graduating trainees shouldn’t be viewed differently, was quite shocking.”

Catenaccio and colleagues analyzed publicly available mean debt and compensation data from 54,479 full-time physicians in academic medicine from 2019 to 2020 to arrive at their conclusions. The researchers generated models of the physicians’ starting salary and estimated salary in the 10th year of employment, annual salary growth rate, and overall earning potential in the first 10 years of employment. The study included 45 subspecialties, including psychiatry.

Compared with men, women in academic medicine had lower starting salaries in 42 of 45 subspecialties and lower salaries at year 10 in 43 of 45 subspecialties. Furthermore, women had slower mean annual salary growth rates in 22 of the 45 subspecialties and lower earning potential in 43 of 45 subspecialties. Psychiatry is one of the medical specialties in which these pay gaps exist.

Among all physicians in the study, just a one-year delay in promotion from assistant to associate professor reduced women’s earning potential by a median of $26,042, and failure to be promoted at all reduced earning potential by a median of $218,724 over 10 years. Equalizing starting salaries between men and women could increase women’s earning potential by a median of $250,075 over 10 years in the subspecialties for which starting salaries of women were lower than those of men, according to the researchers. Similarly, equalizing annual salary growth rates could increase women’s earning potential by a median of $53,661 over 10 years in the specialties for which mean annual salary growth rates were lower for women than for men.

A View Toward Equality

Catenaccio and colleagues cited research that suggests that starting salaries may differ between men and women because women do not negotiate as frequently or as successfully as men and that women who do try to negotiate often are penalized disproportionately.

The onus for ensuring equal pay for equal work should fall on the people who do the hiring, such as departmental chairs and academic institutions. —Rashi Aggarwal, M.D.

“Negotiation is a double-edged sword,” said Rashi Aggarwal, M.D., a member of APA’s Council on Medical Education and Lifelong Learning, who was not involved in the research. Aggarwal is the director of the residency training program and a professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School. “It can be that someone says a woman [who negotiates on salary] is too bossy, demanding, or abrasive, but they don’t see men that way.”

Aggarwal said the onus for ensuring equal pay for equal work should be on the people who do the hiring: the chair or the department and the institution.

“It’s systemic factors that led us to where we are,” Aggarwal said.

Yet Aggarwal acknowledges the importance of financial savvy and fact-finding when women are offered positions in academic medicine. “It requires knowing the market and finding out what salaries are being offered. I don’t understand why salaries have to be a dirty secret. Make them available and explicit.”

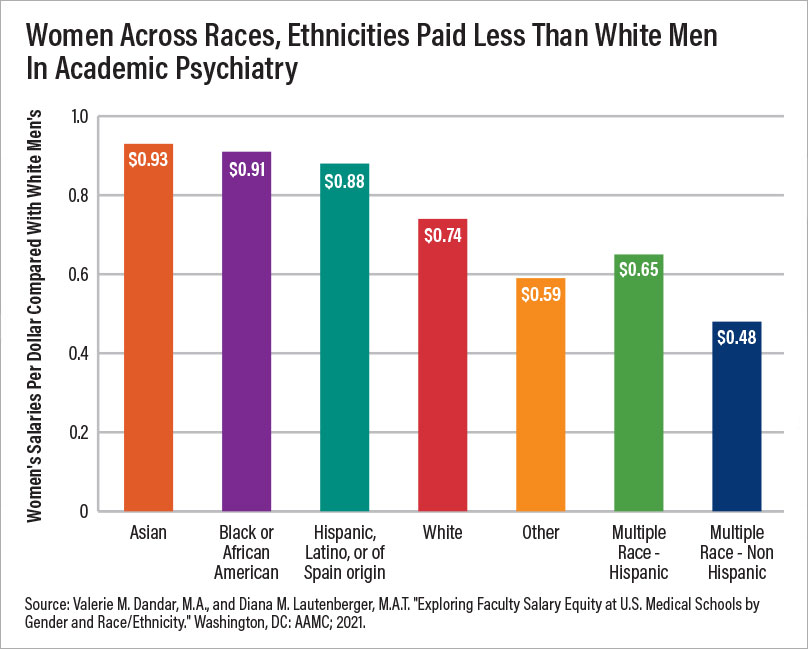

The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) 2021 report “Exploring Faculty Salary Equity at U.S. Medical Schools by Gender and Race/Ethnicity” offers a snapshot of salaries in 154 medical schools, although women will probably not like what they find there. Among faculty with M.D. degrees in clinical science departments/specialties, women across races and ethnicities were paid between 67 cents and 77 cents per $1 compared with White men. In psychiatry departments, for every $1 a White man earned, Asian women earned 93 cents; Black or African American women earned 91 cents; Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin women earned 88 cents; White women earned 74 cents; women who identified as Other earned 59 cents; Hispanic women of multiple races earned 65 cents; and non-Hispanic women of multiple races earned 48 cents. (Sample sizes were too small to report a comparison for women who were American Indian or Alaskan Native and women who were Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander.)

Aggarwal expressed disappointment at the figures in both the JAMA Open Network paper and the AAMC report.

“We want to believe this isn’t happening, and so often we assume it’s not, until it’s in our face that it is,” Aggarwal said, adding that there is no denying the data. “But having more transparency does help, so it’s a good thing that we can see [these data] because it makes it harder to continue gender discrimination. We need to have more studies like this that make [the salary gap] explicit.”

Time to Level the Field

In a commentary in JAMA Network Open, Mariana P. Socal, M.D., Ph.D., an associate scientist in the Department of Health Policy and Management at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and colleagues wrote that the researchers’ findings point to several potential solutions for addressing the pay gap between women and men in academic medicine. These include ensuring that starting salaries are similar across genders; providing women who are already in the workforce periodic opportunities to have their compensation reviewed and adjusted; and offering women equitable opportunities to increase their earning potential, such as opportunities for leadership positions.

“[I]t is important that [periodic compensation evaluations and adjustments] take into account the complexities of physician compensation beyond the negotiated salary, examining aspects such as bonuses, clinical incentives, compensation for leadership positions, and others, while also recognizing these are often differentially provided to men,” Socal and colleagues wrote.

Yet several barriers stand in the way of those solutions, said study researcher Jonathan Rochlin, M.D., a pediatric emergency medicine specialist in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn, N.Y.

“There is a lack of salary transparency and easy access to salary benchmarks [and] there is insufficient education in medical schools surrounding the topics of finances, employment contracts, and salary negotiation,” Rochlin said. “But hospital leaders should want to attract the brightest and most motivated individuals. Ensuring equity among providers, including compensation, is a crucial part of maintaining a diverse workforce and ultimately providing balanced access to health care for patients.”

Mentoring female trainees on how to navigate salary negotiations, including guidance on appropriate compensation, can be invaluable, added study researcher Harold Simon, M.D., M.B.A., a professor of pediatrics and emergency medicine and vice chair for faculty in the Department of Pediatrics at Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. “It’s up to medical educators and leaders to ensure that access to excellent mentorship is available for all, including female trainees and junior faculty.”

Aggarwal agreed. “Where we can help women faculty is by helping them with the things that will get them promoted, [such as] representation on committees and academic writing, and teaching them how to save time in their workday so they can do that.”

Catenaccio feels the time has come to shift from raising awareness of gender-based disparities to developing programs that actually address them. “The impact of these programs then can be studied and, if successful, lead to widespread implementation. I hope if we repeat the study in 10 years, we won’t find the same results.”

The researchers’ study was supported by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Department of Pediatrics Diversity Endowment, the Emory Open Access Publishing Fund, and the Maimonides Hospital Department of Emergency Medicine. ■