Special Report: How to Work With Patients Using Problem-Focused Psychodynamic Psychotherapies

Abstract

Long-term intensive psychoanalytic approaches can be modified as shorter-term focused interventions for particular problems and disorders. By addressing underlying dynamics of these difficulties, the treatment may have a broad impact on psychopathology.

Psychoanalytic approaches have become marginalized in psychiatry in recent years due to several factors, including the length and complexity of the interventions and the limited research on these treatments. Psychoanalytic theory and clinical writings have often been couched in complex terminology and viewed as untranslatable into manualized form. Many psychoanalysts have believed that these approaches did not require systematic studies, as clinical work demonstrated their effectiveness.

In addition, rather than being tailored to specific problems, psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapy were generalized approaches that did not target particular difficulties, limiting their utility for patients who want a specific problem or disorder addressed. Indeed, many psychoanalysts have believed that if specific symptoms are targeted and resolved with treatment, they will be replaced by others until central unconscious conflicts are interpreted.

However, beginning in the mid-1980s clinicians began to develop manualized psychodynamic treatments, heralded by Luborsky’s Manual of Psychodynamic Psychotherapy. Our psychodynamic research group at Cornell (including Barbara Milrod, M.D., Arnold Cooper, M.D., Theodore Shapiro, M.D., and the author) developed a manualized treatment of panic disorder in the 1990s, Manual of Panic Focused Psychodynamic Psychotherapy, subsequently revised to address a fuller range of anxiety syndromes.

Research studies spearheaded by Milrod subsequently demonstrated the efficacy of this manualized approach for panic disorder in randomized, controlled trials. The process of manualization and systematic study required an effort to make psychoanalytic concepts more comprehensible and user friendly and to develop shorter term interventions. The efficacy and brevity of these psychodynamic treatments facilitate their broader use in public health settings.

Subsequently, several psychoanalytic manuals have been developed focusing on specific disorders, including depression; posttraumatic stress disorder; behavioral change; and personality disorders, most commonly borderline and narcissistic disorders. (In this article, I do not discuss severe personality disorders, a subspecialty area of focused dynamic treatments, although personality factors are attended to in addressing other problems.)

These focused manuals are based on the notion that specific dynamics are associated with specific disorders, requiring modifications of psychoanalytic technique. These approaches include identifying the context and emotions, relevant representations of self and others, intrapsychic conflicts and defenses, and mentalization difficulties associated with specific symptoms or problems. The resulting formulation of these factors can then be used as a framework to target specific disorders.

Dynamic Formulations Identified for Specific Disorders

On the basis of extensive reviews of clinical and research literature and direct clinical experience, my colleagues and I have developed formulations for specific disorders.

For example, studies and clinical work indicate that individuals prone to developing panic disorder had early life separation fears that led them to feel fearfully dependent on their caretakers. Many patients described histories of adverse developmental events or trauma and poor family management of anger and separation. These individuals had difficulty managing angry feelings and fantasies, which they feared (often unconsciously) would damage or disrupt already insecurely attached relationships. Furthermore, these angry feelings were exacerbated by disappointment with perceived or actual unresponsive, critical, or rejecting behavior by caregivers.

My colleagues and I found that panic attacks were triggered in the context of perceived threats to attachment, such as a loss (either in reality or symbolically) or a movement toward increased autonomy. In these circumstances, patients become fearful of abandonment as well as frightened and guilty that their anger would damage or destroy needed relationships. Defenses triggered include denial, reaction formation, and undoing, which attempt to modulate and control angry feelings and fantasies and increase affiliative efforts.

Despite these defenses, a vicious cycle is triggered in the form of fearful dependency-anger-anxiety-fearful dependency, ultimately leading to panic attacks. The panic attack itself modulates the threat from anger through a defensive focus on the body (somatization). In addition, the individual appears to himself and others as ill and nonthreatening rather than as angry or damaging. Furthermore, the pain of the panic attack can serve a self-punitive function for guilt-inducing aggressive and dependent wishes.

In a similar review of clinical literature and psychological studies, my colleagues and I determined that core dynamics of depression surround vulnerability in self-esteem. Patients with depression also demonstrate conflicts regarding anger, often triggered by self-esteem vulnerability—for example, feeling rejected or criticized—leading to guilt and fears of damaging others. This anger typically becomes directed inward in the form of self-attacks, propelling a vicious cycle of worsening self-esteem. Given the psychodynamic overlap, addressing conflicts about anger usually helps alleviate both anxious and depressive symptoms, as well as associated problems in interpersonal relationships. In another dynamic, patients develop compensatory high expectations of self and others, leading to recurrent disappointments, further lowering self-esteem.

With regard to trauma, psychoanalytic theory and clinical work suggest that individuals unconsciously tend to repeat traumatic events, often in an attempt to master circumstances in which they felt helpless. A central defense is identification with the aggressor, in which patients have fantasies of harming others as they have been harmed, frequently triggering intense guilt and self-punishment. A manual of trauma-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy has shown promise in treatment of veterans with PTSD.

Another recent manual targets behavioral change using psychoanalytic interventions. This is anathema to traditional psychoanalytic approaches, which suggest that efforts to change behavior are disruptive to the transference, rendering the treatment ineffective. But psychodynamic approaches are particularly well suited for this purpose, given the exploration and addressing of multiple contributors to problematic behavior. Techniques outside the norm of psychodynamic interventions include identifying a goal of behavioral change and addressing factors that interfere with it; homework and diaries can also be of value.

While such manuals are important for clinical and research work with specific problems, most patients suffer from a broader range of difficulties than those involved in a specific disorder, benefitting from a transdiagnostic perspective. These approaches have therefore been modified into a more general form of intervention called Problem Focused Psychodynamic Psychotherapy (PrFPP), an overarching treatment of these various issues. Interventions include developing a list of patient problems, identifying the problem focus in a given session, and elaborating dynamics that may be specific to or overlap in various problems. The therapist then uses these dynamics as a framework to address the various symptoms, relationship difficulties, personality issues, and behavioral problems with which patients are struggling.

Similar to other focused psychodynamic psychotherapies, in PrFPP the therapist is more active and provides more psychoeducation than in traditional psychoanalytic treatments. Core dynamics, trauma, and adverse developmental events are addressed as they contribute to various difficulties, including in the transference. A psychodynamic formulation for problems is identified and communicated to the patient. In a working-through process, problems are connected with various conflicts, defenses, and relationship issues as the sources and solutions to problems are increasingly identified, and factors interfering with change are also addressed.

Termination of PrFPP and other focused psychodynamic psychotherapies differs from that of traditional psychodynamic psychotherapy in that there can be a more systematic assessment of patients’ progress in addressing various problems. Nevertheless, the usual approaches to transference/countertransference and interpretation of conflicts and feelings in response to separation from the therapist are employed.

Initial Phase of PrFPP: Identifying Problems

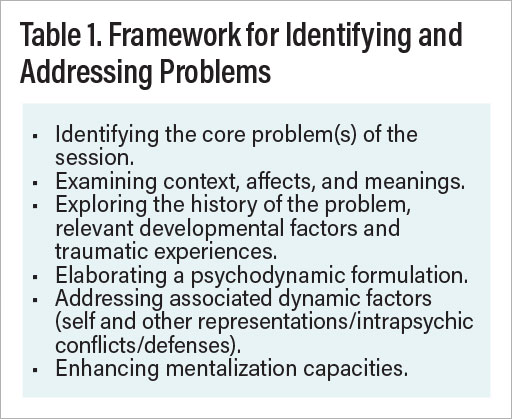

For the purposes of this treatment approach, types of problems are designated as symptoms, personality factors, relationship difficulties, and/or behavioral issues. However, problems can fall into overlapping categories; for example, difficulties with assertiveness can fit into any of these categories. Therefore, the language and components of problems are defined by the therapist and patient as they elaborate understanding of and approaches to areas of difficulty (see Table 1).

An initial step involves identifying problems that are often not recognized by patients. For example, somatic symptoms may be viewed as a medical problem. Patients may be too embarrassed or guilt ridden to acknowledge a problem, such as obsessive-compulsive behavior. They may not be aware of certain difficulties, as with personality problems, or they may be in denial, as with substance use. Efforts are also made to define the extent and impact of problems. For example, patients with generalized anxiety disorder may also suffer from a range of associated phobias, inhibitions, and interpersonal problems.

Identifying the Circumstances, Feelings, And Fantasies Surrounding Problems

The therapist then works with the patient to determine the contexts, emotions, and fantasies contributing to problems. Some problems have clear precipitating events and affects whereas others may not, but most are exacerbated by particular circumstances and feelings. Patients are frequently unaware of these precipitants or may unconsciously avoid recognizing them due to the distress they create. A detailed examination is therefore necessary to identify relevant contexts, emotions, and thoughts. The therapist notes the specificity of certain triggers and suggests that these are meaningful and important to investigate and works to engage the patient’s curiosity and collaboration in this search for contributors to problems.

Elaborating the History of the Problem, Relevant Developmental and Traumatic Experiences

In a further step, the therapist and patient work to identify relevant developmental history and traumatic experiences and link them to problems. The contexts and emotions that trigger problems typically derive from particular developmental and/or adverse events. Patients often are not aware of how certain past experiences, including traumas, have affected their lives and contributed to symptoms. Making patients aware of these connections can reduce the overestimation of danger and feelings of lack of control of current circumstances and problems.

Often patients have not recognized links between problems, internal states, and environmental stressors. This lack of connection may derive from not having considered or examined the context and history of problems; thus, the therapist helps develop patients’ skills for identifying links. These linkages also may be repressed or dissociated due to painful affects or conflict, creating an aversion to recognizing connections. The therapist points out when patients do not acknowledge an evident connection, exploring the discomfort with these links.

TIdentifying Relevant Psychodynamic Factors (Self and Other Representations/Intrapsychic Conflicts/Defenses)

Elaborating the context of problems is an initial step in identifying contributory dynamic factors and developing a psychodynamic formulation. This formulation is used as a roadmap to approach problems, increasing patients’ understanding and control over their difficulties. Psychodynamic factors that contribute to problems include particular self and other representations, developmental experiences, traumatic events, intrapsychic conflicts, defenses, and mentalization deficits. Developmental factors include perceptions of salient relationships among family members or other caregivers and cultural factors. Adverse and traumatic events include significant losses, deaths, separations, severe family conflict, physical abuse, sexual abuse, poverty, negligence, and violence within the community.

Elucidation of intrapsychic conflicts is a core part of the psychodynamic formulation and identifying them is a key aspect of psychodynamic treatments, including PrFPP. Conflicts involve unconscious wishes or fantasies and the internalized prohibitions and emotional reactions they trigger, such as guilt or anxiety. Two wishes can also be experienced as contradictory and in conflict, such as to care for and hurt the same person. Although unconscious conflict is universal, individuals can struggle with more severe forms that cause psychopathology and other problems. Certain core conflicts, such as wishes to hurt others, dependent wishes, and sexual fantasies are relevant to the dynamics of many disorders and difficulties. As noted above, conflicts about angry feelings and fantasies are common sources of conflict in depressive, anxiety, and posttraumatic disorders.

Defense mechanisms are the ways in which patients defend themselves from painful affects, negative perceptions of themselves and others, or threatening unconscious fantasies. Defenses typically operate unconsciously; an important therapeutic task is helping patients become aware of how these defenses operate. Several defenses play a role, for example, in attempting to manage angry feelings and fantasies. These include reaction formation, in which the individual adopts a compensatory submissiveness or caretaking of others toward whom they are actually angry. In the defense of undoing, individuals symbolically or verbally take back an angry expression or wish. They might be heard saying of a partner, “I hate him, but I really love him.” While such defenses occur normally or can be associated with any disorder, they are common in panic and other anxiety disorders, in which the individual is attempting to manage anger and make his or her attachment feel more secure.

Addressing Mentalization Deficits

Mentalization is the capacity to conceive of and interpret behaviors and motives in self and others in terms of mental states. Therapists work to determine mentalization difficulties that contribute to specific problems. Mentalization is most likely to be disrupted in close attachment relationships, impairing the ability to communicate about needs and wishes. Many problems result from a misinterpretation of the behavior of others or anticipation of certain actions and attitudes. An improved comprehension of the motives and communications of others can aid in relief of these problems. For example, a patient who is vulnerable to others’ criticisms may be helped by recognizing others may be acting on the basis of their own problems, rather than the patient’s.

Formulating a Framework to Address Problems: Case Study

The framework for identifying and addressing problems includes identifying the core problem(s) of the session; examining relevant context, affects, and meanings; exploring the history of the problem and developmental factors; elaborating and addressing the dynamics, including self and other representations, intrapsychic conflicts, and defenses; and building mentalization capacities.

The following is a case example:

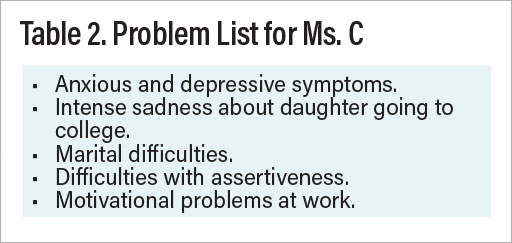

Ms. C, a 46-year-old married woman working in public relations, presented with a primary complaint of anxious and depressed mood, including decreased motivation and interest, reduced appetite, and decreased concentration. She also described social anxiety and fears of confrontation. The therapist concluded she met criteria for generalized anxiety disorder with possible major depressive disorder and would benefit from a trial of escitalopram. Based on the stressors in Table 2 on the next page, the therapist told her that psychological and emotional factors contributed to these symptoms and recommended weekly psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Exploring the History and Context of Problems

The therapist explored the onset of the depressive and anxious symptoms to identify contributors to these problems. The therapist and patient determined that the problems had occurred in the context of the patient’s daughter, Heather, the youngest of two children, applying for college. Ms. C reported that she and Heather had always been “very close,” and she was feeling upended by intense sadness about her daughter leaving home.

In exploring the history of this problem, the therapist learned that the patient had significant difficulty with Heather’s aging over many years. She was very attached to the time before Heather was 10, when Ms. C returned to work and felt sad about the loss of childhood activities they had done together. Indeed, Heather never attended camp or sleepovers and spent much of her time, well into adolescence, at home rather than going out with friends.

Her relationship with Heather had intensified when she was age 5 and her husband, an entrepreneur, was working hard and often not home at night. She described Jim as not only very busy at that time but increasingly irritable and critical as he became more successful. Subsequently, however, Jim suffered setbacks in his business. He recently worked very little, although he was always considering new projects. She earned the bulk of the family income.

Ms. C: With her going off to college, I feel so sad, and I’m worried it will get worse.

Therapist: What do you anticipate it will feel like?

Ms. C: I’m worried about feeling lonely or empty. Jim and I have a lot of problems, and we’re pretty distant. I’ve asked him to go to couples therapy, but he objected, and I don’t want to create trouble with him.

Therapist: What problems would that cause?

Ms. C: I’m worried he’ll just get mad if I keep bringing it up. I’m fearful of asserting myself and don’t push for what I want. After he objected, I just withdrew and gave up.

Therapist: What frightens you about asserting yourself?

Ms. C: I worry it’s going to create a rift. It’s like that with my father. I get angry at his criticisms, but I’m hesitant to say anything to him. It’s true with my boss as well. I’m frightened about asking him for a raise, even though in the past he’s been responsive when I asked.

Therapist: So it sounds like a pattern?

Ms. C: Yeah, I guess I never really liked confrontation.

Problems as Linked to Developmental Factors

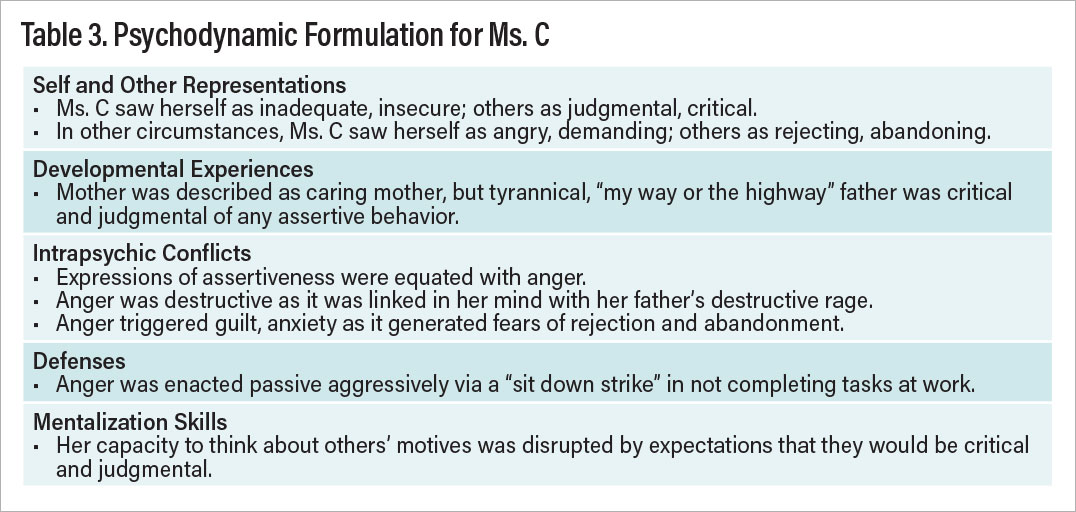

In describing her background, Ms. C noted that though she had felt very close to her warm and responsive mother, her father was judgmental and controlling, and Ms. C felt she could never meet his expectations. Ms. C felt frustrated with him recently, as he was critical of the college his granddaughter was going to and expressed his feelings by becoming distant. However, she felt frightened of confronting him about his attitude, as he would typically react in an angry manner and withdraw from the family for days. The therapist was able to link her fears of confronting her husband and asking her boss for a raise to the danger that she felt with her father, anticipating that they would respond angrily to her assertiveness. The therapist and patient also identified that she equated any expression of frustration with her father’s temperamental damaging anger, triggering guilty feelings.

Ongoing Emergence, Clarification of Problems

In PrFPP, problem lists are not considered static, as there is a clarification of problems already being explored. In this model of therapy, new problems can be identified as blocks to revealing existing problems (denial, guilt, intrapsychic conflict, and defenses) and are addressed as they emerge with further exploration. For example, Ms. C revealed that her motivation and productivity at work diminished, especially after she felt that her boss favored a new hire and that he received a higher salary. The therapist surmised that Ms. C could not express her frustration directly by seeking a raise and instead behaved passive aggressively. The therapist built upon the developing formulation, suggesting, “I believe that your motivational problems at work are related to believing your boss will behave in rejecting, critical ways like your father. You don’t feel safe expressing your frustrations directly, so you enact them indirectly via a sit-down strike.”

Psychodynamic Formulation for Ms. C

Elements of the psychodynamic formulation are summarized in Table 3.

Further Clinical Interventions

Based on the framework of the psychodynamic formulation, the therapist suggested that confronting others was unlikely to lead to the anticipated abandonment or rejection she feared, and her anger was not as dangerous or damaging as she anticipated. It was important to recognize how fear of her boss stemmed from that of her father, as her boss had not responded in an attacking fashion when she asked for raises in the past. As she continued to struggle with asking for a raise, her fears could be addressed in the transference, as she felt the therapist would be angry and disappointed with her for not completing this therapeutic “homework.” The therapist summarized: “I believe you’re overestimating the danger of these disruptions with your husband and boss occurring because it’s so frightening to you to feel cut down or disregarded by your father. You believe raising any of your concerns is a threat to your close relationships.”

As Ms. C increasingly recognized she could feel safer expressing her frustrations, her husband and boss were more responsive to her assertions than she anticipated. The increased satisfaction she felt at work and at home eased her intense feelings of loss regarding her daughter’s departure.

Conclusion

As termination approaches, therapists and patients can examine the progress they have made with various problems and work to address remaining areas of difficulty. They also explore patients’ reactions to ending therapy. Feelings and fantasies about separation and anger can be addressed as they emerge directly with the therapist, enabling increased tolerance and better management of these emotions and a consolidation of gains. Further efforts are made to improve mentalization skills, helping patients to identify contributory factors and address warning signs of problems recurring after treatment has ended.

Evidence indicates that long-term intensive psychoanalytic approaches can be modified into effective focused interventions for particular problems and disorders. By addressing underlying dynamics of these difficulties, these treatments may have a broad impact on various aspects of patients’ psychopathology and their lives and provide relief of suffering over shorter time periods. However, extensive research is needed to identify which treatments work best for which patients over the short and long term. At this time, multiple psychodynamic manuals exist for gaining clinical skills in these approaches and facilitating research. ■

Author Disclosure Statement

Fredric Busch, M.D., receives royalties from American Psychiatric Press, Taylor/Routledge, and Oxford publishers. He has no other financial conflicts to disclose.