Children With Autism, Fragile X Show Distinct Early Brain Changes

Abstract

The brains of children with autism spectrum disorder appear to diverge from other children between 6 and 12 months of age, pointing to a key period when early intervention may have a strong impact.

Most children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are not diagnosed with the disorder until between the ages of 2 and 3 years. A study in the American Journal of Psychiatry suggests that the brains of babies who go on to develop ASD may be distinguishable from those who do not develop the disorder as early as six months of age.

“[P]resymptomatic brain changes in infancy may represent a cascade of linked brain and behavior changes that lead to the emergence of the full syndrome of autism,” wrote Mark Shen, Ph.D., an assistant professor of neuroscience and psychiatry at the University of North Carolina, and colleagues. Understanding these brain changes could inform targeted interventions.

Mark Shen, Ph.D., says the abnormal amygdala growth seen early in development of children later diagnosed with autism might be related to visual processing deficits.

Shen and colleagues were particularly interested in the development of the amygdala, a brain region involved in processing emotions.

“The amygdala is the key hub that processes the social meaning of sensory information,” Shen said. “For example, it is the amygdala’s job to help babies match facial expressions with the appropriate emotion, which is a fundamental building block for future social ability.”

While studies of children aged 2 to 4 years have pointed to amygdala enlargement in children with ASD, when these changes take place and how they relate to key features of ASD were unknown.

“Our goal was to identify how early in life this overgrowth occurs and whether it’s unique to ASD,” Shen told Psychiatric News.

The study was conducted by investigators from the Infant Brain Imaging Study (IBIS) Network, a consortium of 10 universities across the United States and Canada that is funded by NIH. Over the years IBIS has conducted several neuroimaging studies examining early life brain changes that precede the behavioral symptoms of ASD.

Shen and colleagues performed MRI scans on 408 babies at 6, 12, and 24 months of age as they slept. The participants included 58 babies who had an older sibling with ASD (considered high risk for ASD) and were later diagnosed with the disorder; 212 high-risk babies who were not later diagnosed with ASD; 109 babies with no family history of ASD who were not subsequently diagnosed with ASD; and 29 babies with fragile X syndrome—a developmental disorder caused by mutations in an X chromosome gene called FMR1. Children with fragile X syndrome exhibit a range of physical and behavioral challenges, and about half meet criteria for co-occurring ASD.

The infants with fragile X syndrome were confirmed with genetic testing, and ASD diagnoses were made by clinicians at 24 months using DSM-IV-TR criteria.

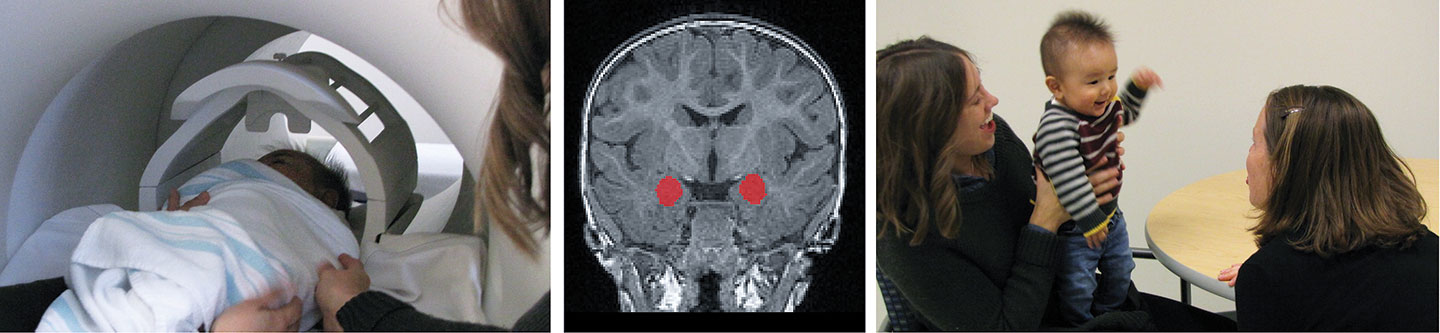

Left: Six-month-old baby asleep during MRI scan, alongside mother and UNC researcher. Middle: The amygdala (in red) grows too rapidly in the first year of life in babies who later develop autism. Right: Baby during a test of social skills.

The investigators found that the MRI scans of infants who were later diagnosed with ASD were similar to the scans of the infants in the other groups at six months of age. Over the next six months, however, they exhibited abnormally increased amygdala growth, relative to all other groups, such that their amygdala volume was 5% larger than the other groups at 12 months of age, and 4% larger at 24 months.

This increased growth rate of the amygdala was also associated with future autism behaviors; infants with the fastest rate of amygdala growth between 6 and 12 months had greater social deficits on average when they were diagnosed with ASD at 24 months.

The study also found that the volume of the caudate (a brain region that regulates movements and procedural learning) was about 20% larger in babies with fragile X syndrome than all other groups at 6, 12, and 24 months of age. Caudate size was also linked with subsequent behaviors; babies with fragile X syndrome who had larger caudates at 12 months displayed more repetitive behaviors at 24 months.

As a control, the IBIS group also analyzed the growth of the thalamus (a brain region that is a relay station for all incoming motor and sensory information), which has not been implicated in ASD. They found that thalamus growth was similar for all the infant groups.

Shen told Psychiatric News that the abnormal growth of the amygdala during the first 12 months of age might be related to altered growth of other parts of the brain that control visual processing in children with ASD. Normally, as the amygdala matures and begins to match sensory inputs with emotional outputs, unused connections between brain cells are pruned back to increase efficiency, he said. Because of visual processing deficits, babies who develop ASD may not receive the correct sensory information to the amygdala, which would limit pruning and may lead to excess amygdala growth.

The findings point to a need for interventions for children with ASD and/or fragile X in the first year of life, said Randi Hagerman, M.D., a Distinguished Professor of Pediatrics and Endowed Chair in Fragile X Research at the University of California, Davis. She noted that treatment for children with ASD and fragile X syndrome typically begins when the child reaches two years. Given the MRI findings, Hagerman suggested that early life visual and language therapies could be valuable, and in the case of children with fragile X, such therapies could be supplemented with low-dose sertraline, which helps boost early neuron development while also managing childhood anxiety symptoms.

Shen’s team is currently recruiting new infants with fragile X and infants with an older sibling with ASD for a new NIH-funded study to replicate and extend these findings. ■