Making Choices on a Journey

On the last Sunday in July, I attended the 10 a.m. service at the Friendship Baptist Church in Atlanta. I was in the company of a longtime psychiatrist friend, Professor Quentin Ted Smith. It was a joyous reunion in the precincts of his home church. I had no idea that Morehouse and Spelman colleges took form in the basement of Friendship Baptist sometime in the 1860s. However, the faith group presently occupies an imposing multi-function modern structure dedicated in July 2017. Dr. Smith and I had become good friends over the years, and I was curious about his recent activities. I considered him one of the tranquil and effective sages in American psychiatry. He was neither garrulous about his talents nor his deeply generous spirit. He is vice chair of education in the Department of Psychiatry at the Morehouse School of Medicine. I believe that we first met years ago at a conference organized by the Black Psychiatrists of America. I had not seen him since I was the guest speaker at a white coat ceremony about 20 years ago at Morehouse.

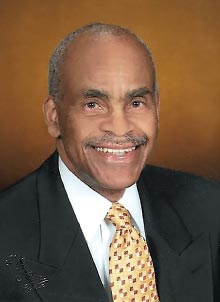

Quentin Ted Smith, M.D., is a professor of psychiatry and vice chair of education in the Morehouse School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry.

I learned that Dr. Smith was a member of the choir slated to sing that Sunday. He was attired, like the other male singers, in a dark suit with a white silk tie and white shirt. Since he is still a half-marathoner and long-distance walker in his ninth decade, he fit into the suit with an understated elegance. He could gain admission to most church choirs anywhere because, as a college undergraduate, he sang first tenor with the Fisk University Jubilee Singers. That is a distinction few can claim. Later, at lunch, he explained that the Black church had long occupied a central space in his life. His music, he said, speaks to others, as does the calligraphy he employs in the letters he pens to members in his church who are grieving loss.

His parents raised him in Brooklyn, where he grew up in the Kingsboro projects. He attended Franklin K. Lane High School and then enrolled at Hunter College, one of the sections of the City University of New York. He felt a bit disheartened by the experience. He seemed to be missing the magic he wanted from the combination of home and school. The Yale psychologist Miraj Desai suggests that such feelings sometimes prompt us to renounce being sedentary and to travel outside our usual confines to seek change. By chance, friends who knew about Fisk University encouraged young Ted Smith to make the move, to take a different fork in the road and travel South. These unexpected encounters can produce decision-making that leads to the most special of places.

I did not ask him whether at that point he was familiar with Robert Frost’s 1915 poem, “The Road Not Taken.” However, his moving to Fisk turned out to make all the difference in his life. Others have also told me stories about how historically Black colleges enter people’s lives and turn things around. He clearly appreciated the intellectual curiosity of this concentrated collection of Black people on a single campus. He was carried away by the wave of positivity and the constructive use of time, place, and energy. Everyone seemed focused, intent on achieving something. He could see it just in the way the students walked. And the professors took the time to be helpful and considerate. From his discourse, I could tell that he models some of his pedagogical style on what he witnessed at Fisk. After the first semester, he was awarded a scholarship. His performance earned him a place in Phi Beta Kappa in his senior year.

He graduated in 1961 and spent a year pursuing a Ph.D. at the University of Chicago in biopsychology. He missed the culture, the interactions, the spirit that had emerged so powerfully at Fisk. He took a year off and reoriented himself toward medicine. Robert Frost was right. It serves little purpose to stay on a disappointing pathway and brood. Alternatively, as a single traveler, he could not stay on more than one road at the same time. Frost makes clear that such simultaneity is not permitted: “Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, And sorry I could not travel both. …” So, Dr. Smith enrolled at the Howard University College of Medicine and found a new home. In it, he established the habits and rituals that Professor Devika Chawla says can restore a person into himself.

Professor Smith completed his medical studies in 1967, loving the experience and noting that his teachers were fantastic. By 1973, he completed specialty training in general and in child and adolescent psychiatry. He taught at Emory University School of Medicine before moving to Morehouse in 1984, where both he and his pathologist wife would build careers as celebrated master teachers and scholars. He modeled the physician role for his charges. Unlike many, he stayed away from administration because it often seemed to carry too much of a “misery index.” He preferred the interactions with trainees curious about healing and caring for others.

He uses the solitude and isolation of his long walks and leisurely promenades around the city to think and recharge his energy. He has enjoyed remarkable privileges in life and has few regrets about his routine choices. Whenever presented with the dilemma of confronting two roads, he took one, recognizing that a choice is simply mandatory. I came away from our encounter repeating Walt Whitman’s lines from “To Think of Time”:

“Something long preparing and formless is arrived and form’d in you, You are henceforth secure, whatever comes or goes.” ■