Resident Performance Evaluations May Be Biased Toward Whites

Abstract

Milestone scores are used by programs to assess residents’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, and more. Lower ratings given to residents of color compared with White residents may hinder residents of color as they embark on their careers.

Internal medicine residents who are Asian or belong to racial groups that are underrepresented in medicine often receive lower ratings on performance assessments than their White peers in the first and second years of postgraduate training, a study in JAMA Network Open has found. The findings suggest a racial and ethnic bias in trainee assessment that may have a far-reaching impact.

Hospitals and academic medical centers should conduct routine investigations of disparities in evaluation of resident competence, says Dowin Boatright, M.D., M.B.A., M.H.S.

“This disparity in assessment may limit opportunities for physicians from minoritized racial and ethnic groups and hinder workforce diversity,” wrote Dowin Boatright, M.D., M.B.A., M.H.S., the vice chair for research at the Ronald O. Perelman Department of Emergency Medicine and an associate professor of emergency medicine and population health at the New York University Grossman School of Medicine, and colleagues. For example, trainee assessments are often considered in decisions regarding promotion, chief resident selection, readiness for unsupervised practice, and entry into competitive subspecialty graduate medical education programs.

The researchers examined data from the performance assessments of 9,026 internal medicine residents from the graduating classes of 2016 and 2017 who were in internal medicine residency programs accredited by the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Among the residents, 50.4% were White, 36.1% were Asian, and 13.5% belonged to groups that are underrepresented in medicine—defined as Latinx only; non-Latinx Native American, Alaska Native, or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander only; or non-Latinx Black. The researchers focused on scoring for the midyear and year-end ACGME Milestones. These Milestones are used by residency programs’ Clinical Competency Committees to assess residents’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, and other attributes in clinical competency domains such as medical knowledge, patient care, professionalism, and others.

The researchers separated Asian residents from other residents of color partially because Asians are overrepresented in medicine relative to their representation in the general population and partially because of variability in racist biases, Boatright explained.

“Studies have demonstrated that there are differences in the type of discrimination people experience based on race, and there is an idea that Asians are the ‘model minority’ where biases toward them may operate differently,” Boatright told Psychiatric News.

Yet the results suggest that Asian residents may experience more discrimination in their first postgraduate year (PGY-1) assessment than other people of color: midyear total Milestone scores were a median of 1.27 points higher for White residents compared with Asian residents, whereas there was no significant difference in PGY-1 midyear total Milestone scores between White residents and residents from groups underrepresented in medicine.

Not ensuring that residents are assessed fairly makes their working environment hostile to them, says Nientara Anderson, M.D., M.H.S.

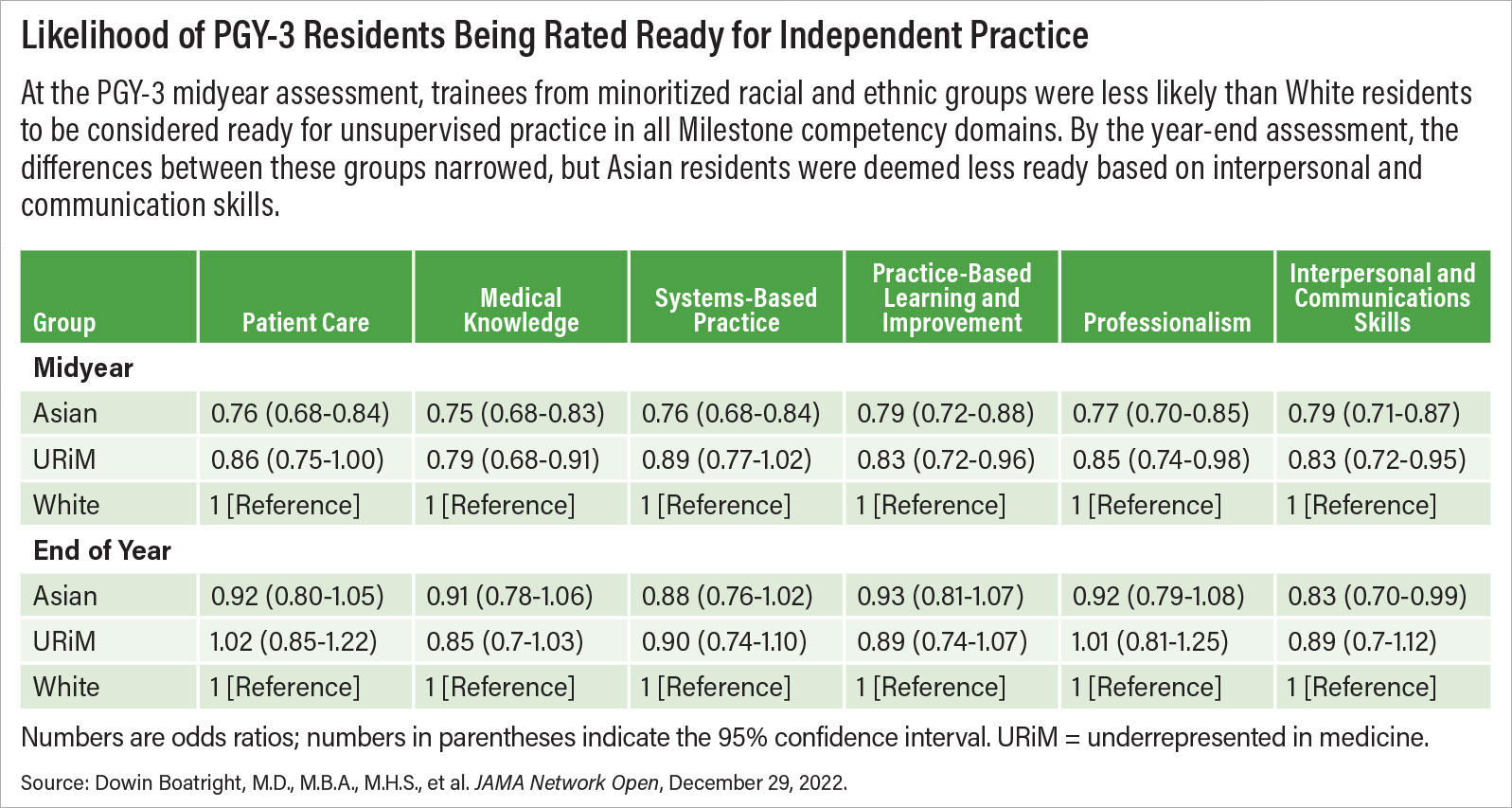

From the midyear PGY-1 assessment onward, White residents began to receive increasingly higher scores compared with Asian residents and residents from groups underrepresented in medicine. These disparities peaked in PGY-2, when White residents’ total scores were a mean of 2.54 points higher than those of residents from groups underrepresented in medicine and 1.9 points higher than Asian residents. However, the gap in scores narrowed by the PGY-3 year-end assessment, when the researchers found no racial and ethnic differences in the total Milestone scores.

The researchers also found differences in the ratings for individual clinical competency domains between White residents and Asian residents and residents from groups that are underrepresented in medicine, with White residents scoring higher than the other groups.

“As the findings suggest, representation alone cannot solve racism,” said study researcher Nientara Anderson, M.D., M.H.S., a psychiatry resident in the Neuroscience Research Training Program at Yale University School of Medicine. “Recruiting people and not ensuring that they are assessed fairly makes the environment hostile to them. As long as there are racist attitudes and structures, simply increasing [the number of people of color in medicine] does not obviate the presence of racism.”

One finding may highlight how racial and ethnic inclusiveness and equity at all levels of medicine may counter racism toward residents: When the researchers analyzed data from residents who completed their training at historically black colleges and universities, they found no significant racial and ethnic differences in total Milestone score and no differences in the ratings for any competency domain during residency.

“Although there’s a potential for that result to be biased because of a small sample size, the faculty at these institutions are generally more diverse, and data have shown that positive social contact among different groups can reduce implicit bias,” Boatright said.

Boatright encourages hospitals and academic medical centers to assess themselves for bias in evaluating resident competence.

“What I fear is that some programs will see our data and assume that it’s only about other programs and not theirs,” Boatright said.

This study was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. ■