Ketamine Comparable to ECT for Many Patients With Refractory Depression

Abstract

Following a presentation of new clinical trial data at the Annual Meeting, some questioned why patients were limited to only nine doses of ECT instead of the typical 12 to 16 sessions.

Ketamine is about as effective as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for patients with treatment-resistant depression without psychosis, a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine has found. Amit Anand, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and principal investigator of the ELEKT-D clinical trial, presented these findings during APA’s Annual Meeting in May.

“The reason ECT has been around 80 years is because it is an effective and fast-acting treatment,” Anand told the audience. However, some patients are worried about cognitive side effects, he continued, so it is worth examining how alternative options for treatment-resistant depression compare, he continued.

To compare ketamine with ECT, Anand and colleagues recruited adults aged 21 to 75 who had been referred by their clinical providers for ECT. The participants met the criteria for a DSM-5 diagnosis for major depressive disorders without psychotic features. All participants were required to have a score greater than 20 on the 60-point Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), indicating moderate to severe depression, and to have failed to respond to at least two adequate trials of antidepressant treatment.

The study was designed to mimic real-world outpatient clinical care as much as possible, Anand noted. The trial was open label, participants could continue all their existing medications, and clinicians could adjust treatment as needed.

The 403 enrolled participants were randomly assigned to three weeks of ECT (initially right unilateral ultrabrief but could be switched to bilateral delivery) three times a week or ketamine (initially 0.5 mg per kilogram of body weight over 40 minutes) two times a week.

The primary outcome was patient-reported treatment response, defined as at least a 50% decrease on the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-Report (QIDS-SR).

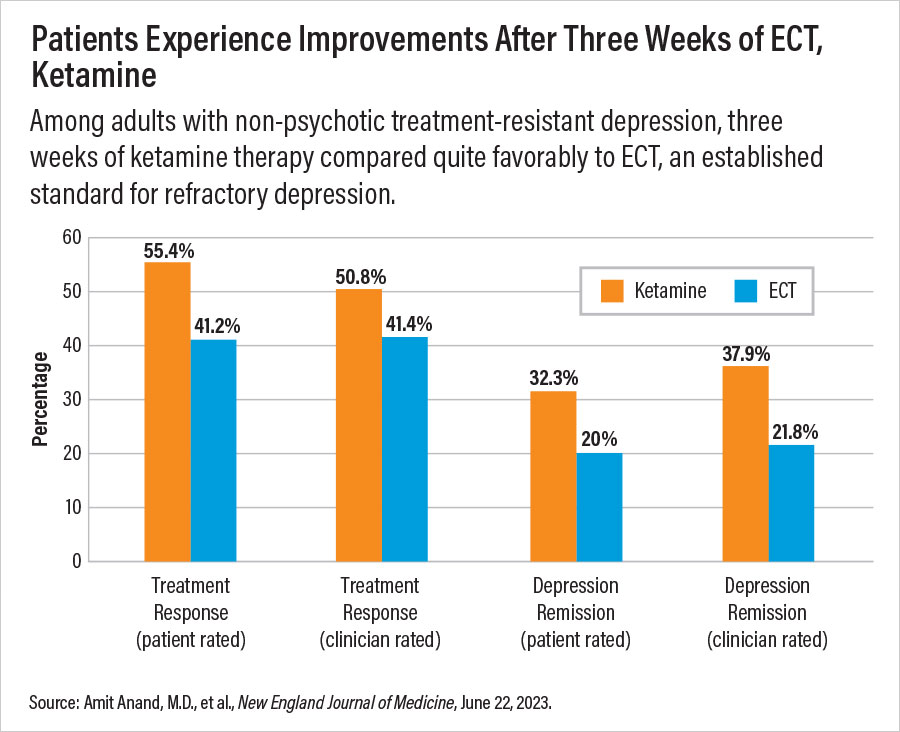

After three weeks, 55.4% of participants in the ketamine group and 41.2% in the ECT group reported a response to treatment. Ketamine was also associated with a higher remission rate on QIDS-SR (score of less than 5) than ECT: –32.3% versus 20%, respectively. Anand noted that ketamine outperformed ECT in other outcomes as well, but since the trial was designed as a non-inferiority comparison, future trials are needed to determine whether ketamine could be superior to ECT for some patients.

The participants receiving ECT reported greater memory declines at the end of treatment compared with those who received ketamine, though at the one-month follow-up there was little difference between the two groups. Among other side effects, ECT participants reported more musculoskeletal adverse effects, whereas ketamine participants reported more dissociation symptoms.

Anand noted that these latest findings seem to contradict those of a 2021 study, which concluded that ketamine was not as effective as ECT. There were several differences between the populations of patients included in the two trials, Anand said; for instance, the 2021 trial included hospitalized adults and those with psychotic depression—a population known to respond to ECT.

During a spirited Q&A session at APA’s Annual Meeting, multiple people in the audience questioned whether the authors’ decision to limit ECT to nine sessions across three weeks skewed the study to favor ketamine; they pointed out that previous ECT trials have indicated that 12 to 16 sessions are optimal for treating acute symptoms. Anand countered that as a pragmatic trial, ELEKT-D reflected routine practice, which has found most patients receive six to nine ECT sessions before stopping for whatever reason.

“I agree that with three more sessions, the response rate for ECT would have gone up,” Anand said. But another week of ketamine therapy would increase the response of those patients as well, he said. In addition, more ECT sessions would increase the number of reported memory problems. “I don’t see any scenario of treatment length where ketamine becomes inferior to ECT,” he said.

The study was supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. ■