Special Report: How Companion Animals Can Participate in Treatment of Mental Illness

Abstract

Accumulating evidence demonstrates the importance of companion animals in the lives of humans. This article discusses the varied ways those animals may participate in the treatment of mental illness.

Animals have co-existed with humans for thousands of years, and over that time many have found unique and successful ways of cohabiting to the benefit and well-being of both species. This is likely due to the fact that animals occupy many important roles in the lives of humans. Every day, animals serve as our companions, our assistants, our co-workers, and our protectors. They are treated like members of our families, participate in our recreational activities, contribute meaning to our social circles, guard us and our property, provide assistance to individuals with disabilities, and provide emotional support. Some even work for us—they herd animals and can detect bombs and drugs.

Not surprisingly then, pet ownership has become widespread in Western societies. It is estimated that two-thirds of all homes (86.9 million) in the United States include a pet; 65.1 million have dogs, 46.5 million have cats, and 11.1 have fish, according to a June 2023 article by Michelle Megna, an editor at Forbes Advisor. Not only are pets prolific, but their presence is socially important. One study showed that children in the United States are more likely to grow up with a pet in their home than a father, according to Peggy McCardle, Ph.D., M.P.H., and colleagues in the book Animals in Our Lives: Human-Animal Interaction in Family, Community, and Therapeutic Settings.

Beyond the social value of pets and/or companion animals, their therapeutic value has also gained increased recognition. Animal-assisted interventions (AAIs) are today rightly seen as a credible mental health service option, and one with less stigma and fewer barriers to entry than other mental health treatments.

Owning a Pet Can Be Good for Us

One of the most frequent comments addressed to Human-Animal Interaction researchers is “Well, of course having a pet is good for you! Everyone knows that.” The reality is that what everyone “knows” isn’t necessarily true, and there are many factors to weigh before advising patients to consider getting a pet or incorporating a pet into treatment plans.

Pet ownership is associated with positive outcomes across the human developmental spectrum. For example, children who grow up with a pet in their home have a reduced incidence of loneliness, depression, and anxiety; take fewer sick days from school; and are less likely to have allergies or asthma, according to a report by Rebecca Purewal and colleagues in the March 2017 International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. They also have higher self-esteem and empathy, are more popular with their classmates, and have increased engagement with education/reading. Likewise, pet ownership among older adults has been associated with reduced loneliness, depression, anxiety, blood pressure, and self-reported ratings of stress. Older pet owners also participate in more physical activity, have greater social functioning, and experience slower decline in physical and cognitive functioning.

Yet we must be cautious about the inferences we make from pet ownership research. On the surface, it appears that owning a pet helps us to become both physically and mentally healthy, but we have to remember that this work is primarily correlational in nature. People prefer to pick their own pets rather than having one assigned to them as part of a research study. This creates a built-in selection bias, and ultimately, we can’t be certain about whether pets make people healthier or healthier people opt to own pets.

This is where we turn our attention to animal interaction studies, in which an animal is randomly assigned to an individual participant in an individual condition of a study. This work has shown a number of benefits of interacting with animals across the human developmental spectrum. Some outcomes for children who interact with an animal include reduced impulsivity, aggression, social withdrawal, and risk behaviors, along with improvements in reading rate and accuracy, memory and categorization performance, adherence to instructions, attention, motivation, and mood. Likewise, for older adults who interact with an animal, reductions have been found in heart rate, muscle tension, skin temperature, blood pressure, and even the risk of falls and hospitalization rates, along with increases in physical activity, walking distance and speed, and walking ability and stability.

A number of theories attempt to explain the benefits stemming from the bond we share with companion animals. One theory is that pets offer a strong and stable conduit of emotional attachment, which can bolster mental health in people with less stable human connections. Another theory postulates that pets provide social support that reduces or buffers the effects of stress on health and relationships with others. A dynamic version of the biopsychosocial model has been used to explain and organize a wide variety of research findings in which dogs were involved in treatment to improve some aspect of human health and well-being.

Nonetheless, it is important to understand that pet ownership is not a risk-free endeavor. Some data suggest that forming a strong emotional attachment to a pet may lead to emotional challenges; for example, strong attachments to pets increase the risk of grief in the event of pet sickness or death. Additionally, some people might prioritize pet interactions to the exclusion of socializing with other humans. Pet care—much like the care of a child or a parent—also involves time, money, and patience.

How Animals May Participate in Mental Health Care

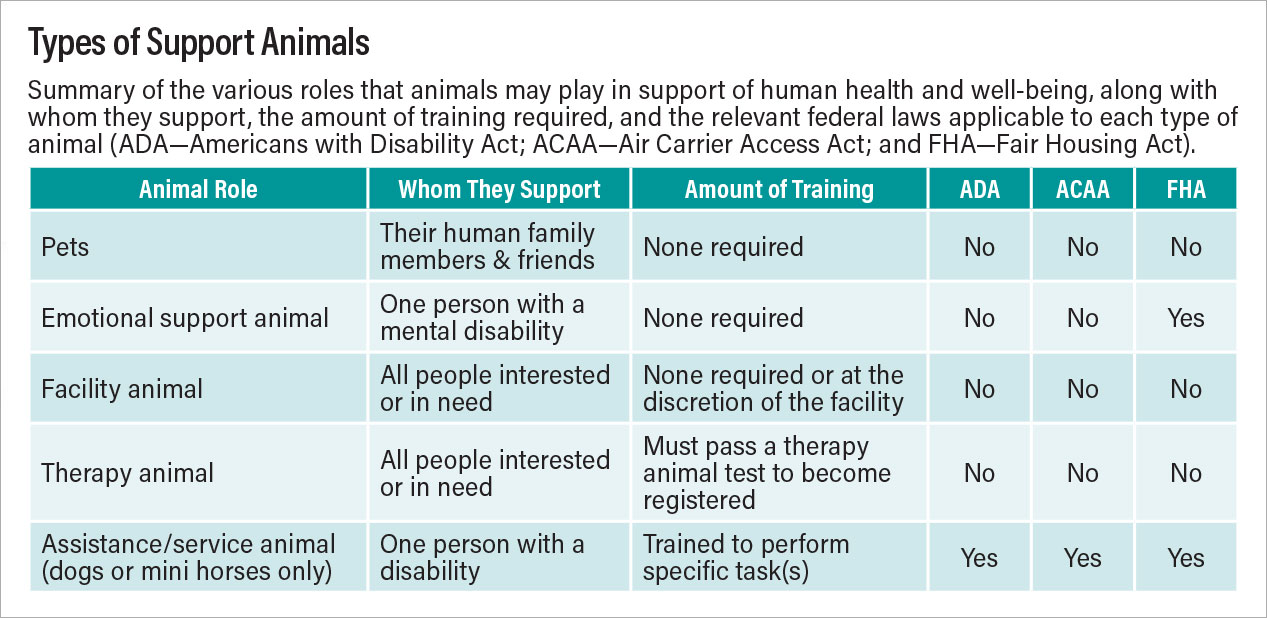

Generally speaking, the ways in which animals may participate in mental health care can be divided into four categories:

Emotional support animal (ESA) is an animal of any species that provides affection and support to one individual who has a verifiable mental illness. An ESA designation requires an individual to obtain a formal document from a licensed mental health professional indicating that the animal improves the person’s condition and is necessary for the individual’s treatment (Points to Consider When Asked to Write Emotional Support Animal Advocacy Letter).

Animal-assisted activities include animals such as facility dogs and therapy dogs that are trained and registered to interact with a wide variety of people for general well-being and motivational, recreational, and social purposes. Typically, therapy dogs accompany their handlers on volunteer visits to various locations such as hospitals, schools, and retirement facilities for short visits, whereas facility dogs accompany their handlers to work each day at the same facility.

Animal-assisted therapy (AAT) involves a health care professional’s incorporating a specially trained animal into goal-directed therapeutic interventions with patients. This practice has been shown to improve the therapeutic alliance, communication, and social functioning. AAT, which can include therapy dogs or equine therapy, should adhere to a set of recognized international standards of practice.

Assistance or service dogs are trained to perform a wide variety of tasks for individuals with disabilities and commonly fall into three categories: guide, hearing, and service dogs. Psychiatric service dogs are different from ESAs because they are trained specifically to perform tasks to aid individuals with a psychiatric disorder such as posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.

It is through these distinct but sometimes overlapping roles that animals participate in the treatment of mental illness and contribute to human mental health. However, we want to point out that AAIs are not recommended as a standalone therapy, but as a helpful adjunct to traditional treatments.

Below are some specific examples of how pets can improve mental health, all of which are discussed in more detail in our book, The Role of Companion Animals in the Treatment of Mental Disorders.

Support Animals and Specific Disorders Stress and Anxiety

Research indicates that interacting with animals can improve indicators of stress in populations as varied as students and health care workers and across the age spectrum. It appears that a preexisting positive attitude toward animals enhances this effect and that interacting with animals is most effective with those struggling with higher levels of stress. Although not all patients may be receptive to AAI, forms of treatment are available for different outcome objectives.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

AAIs are a complementary treatment used by families with children with ASD, particularly for improving communication and social interaction, both in terms of frequency and quality. Although ASD has been the subject of more research involving AAIs than other aspects of mental health, there remains no definitive explanation of the reasons it can be effective. Although parents may be curious about the possibility, the introduction of an animal into the household of a child with ASD should be assessed with regard to whether the hoped-for positive outcomes may be offset by the additional caretaking challenges. Similarly, the form of any therapeutic intervention must be evaluated in terms of the availability of a trained therapist and trained animal, as well as the form of intervention desired.

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Of all childhood psychiatric diagnoses, ADHD is the most prevalent, and the most effective treatment typically involves pharmacotherapy with stimulants. AAI studies suggest that therapeutic interventions with both dogs and horses can also play a role by addressing the deficits in executive functioning that are hallmarks of ADHD. One therapeutic program found to be effective incorporated unstructured bonding time, structured social skills training, and structured dog-themed activities. Less is known about the possible benefits of introducing a pet (typically a dog) into the home of a child with ADHD. Indeed, as with ASD, such a practice may be contraindicated, since the need to train and properly care for the dog may exacerbate existing challenging relationships in the household.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

With the increase in the number of veterans diagnosed with PTSD after returning from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, there has been a parallel increase in the need for effective options to complement the existing pharmaceutical and behavior-based therapies, which aren’t always effective on their own. AAIs appear to support positive outcomes as a part of treatment for PTSD, possibly by promoting a sense of comfort, motivation, and self-esteem. In most cases, animal interactions for those with PTSD take the form of dog ownership. Before recommending such a move, clinicians must carefully consider many issues, such as the financial, emotional, and physical limitations of the owner to care properly for the dog.

Depression

Depression is a common mental health concern, spanning all ages and demographic groups. The introduction of AAI has been found to be helpful in a variety of circumstances, whether through group or individual therapy sessions or other forms of structured or unstructured interactions. The presence of an animal may facilitate a therapy session by increasing engagement with therapy, facilitating rapport between patient and therapist, reducing anxiety that may interfere with therapeutic learning, and improving executive functioning. Whether pet ownership is an effective treatment for depression, however, is not easily evaluated, primarily because individuals self-select to share their homes with pets. This raises cause-and-effect questions about the role pets may play in alleviating preexisting depression.

Brief Notes on Other Populations

Unique elements distinguish certain forms of AAI when used in the context of mental health. For instance, the primary role of dog and handler teams who provide animal-assisted crisis response is to assist in establishing a connection and open communication between survivors and professional medical responders. Thus, in these cases, the human involved is neither a therapist nor an owner, but a handler specifically trained in how best to deploy AAI to provide relief to survivors under the guidance of medical professionals.

Evidence exists to indicate that AAIs can achieve positive outcomes among at-risk youth experiencing adverse child events, although heightened awareness of the potential for aggression toward animals during treatment is vital. Additionally, animals sharing a household with maltreated youth may be subject to similar abuse, and observing intimate partner violence may create problems for both the youth and the animals.

Pet ownership, always difficult to evaluate as an effective form of AAI, can be even more so for older adults whose struggles with the physical effects of aging can have a negative impact on their ability to properly care for a pet. Nonetheless, the need to provide care for a pet can assist with activities of daily living and encourage interactions with the community.

Research suggests that an AAI can help individuals diagnosed with serious mental illness cope with both positive and negative symptoms. However, the potential for aggression in this patient population requires that patients are properly screened before interacting with smaller animals such as cats or dogs; equine therapy may be more appropriate for these individuals.

The integration of AAI teams into a hospice environment has shown positive results in terms of lessening patients’ social isolation and symptoms of anxiety and depression as well as increasing their cooperation with treatment. When a visiting animal belongs to an individual undergoing palliative care, it is important for family members or caretakers to openly plan for the animal’s care following the patient’s passing. This process can provide comfort to the patient by insuring the animal’s welfare.

Considerations When Recommending a ‘Therapeutic’ Pet

To appropriately partner with an animal in a clinical practice or to recommend that a patient or a family acquire a pet, clinicians must have a fundamental understanding of animal welfare requirements. Most people understand the idea of meeting an animal’s basic needs for food, safety, health care, and an appropriate living environment, but clinicians must go beyond these basic considerations and focus on each patient’s needs, abilities, and resources.

These are some questions to consider: Is the patient in a position (physically, cognitively, and financially) to care for the needs of the animal in an ongoing way? Would having a new animal contribute to the patient’s well-being in a positive way or be an additional stressor? What happens to the animal if/when the patient isn’t able to be there to provide for their care? What local laws and ordinances may apply to the patient’s ability to own a pet?

Clinicians should consider asking why the patient wants to acquire a pet and determine whether the reason is realistic or influenced by media portrayals of animals’ abilities and talents. If specific tasks are indicated (for example, waking the patient when having a nightmare), who will be responsible for training the animal to perform those tasks? What type of animal does the patient have in mind, and is that animal right for the job? For example, if the patient wants a horse but lives in an apartment complex, a horse might not be a good fit. Clinicians need to know the patient’s needs and assist in identifying the best fitting animal for that purpose.

Closing Observations

There is much that is not yet known about the ways in which AAIs are best incorporated into the treatment of people with mental illness. It is a difficult area to study, given the extensive number of variables involved. For instance, dogs are the most common species delivering AAI, and the characteristics of the dogs are hugely variable—large, small, curly coated, rough coated, smooth coated—the list goes on. How each of these elements may affect the response of any individual is hard to predict. Still, we do know some things that underlie best practices in AAI.

The appropriate form of AAI will vary from patient to patient, and clinicians must be aware of what options are available and how they should be matched to each patient.

It is essential to respect the health and well-being of the animal involved, including establishing an emergency plan if something goes wrong during an AAI session.

Clinicians involving their own pets as an adjunct to therapy should educate themselves on what constitutes a safe and comfortable working environment for both the animal and patient.

Clinicians should have an established protocol for each AAI session; this will produce a much higher likelihood of success than eclectic or unstructured approaches.

When arranging group therapy sessions or visits from AAI teams to residential facilities, clinicians should prescreen for animal phobias, allergies, or histories of aggression to ensure that all participants are comfortable in the presence of an animal.

Adhering to these guidelines will establish the foundation upon which a successful AAI program can be developed for treatment of a broad spectrum of mental disorders.

Clearly, the decision regarding whether to include an animal in care is not a simple one. Our book, The Role of Animals in the Treatment of Mental Disorders, summarizes extant literature reflecting methodologically stringent research and can be used by clinicians to make evidence-based decisions. ■

Note: The authors have permission to use the photos in which patients appear.

Resources

American Veterinary Medical Association Statement From the Committee on the Human-Animal Bond. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1998; 212(11); 1675.

Amerine JL, Hubbard GB (2016). Using Animal-Assisted Therapy to Enrich Psychotherapy. Adv Mind Body Med. 2016; 30(3): 11-11.

Esposito L, McCardle P, Maholmes V, et al. In; McCardle P, McCune S, Griffin J, et al (eds). Animals in Our Lives: Human-Animal Interaction in Family, Community, & Therapeutic Settings. Baltimore, Md.: Brookes Publishing 2011; 1-5.

Fine AH: Incorporating Animal-Assisted Interventions Into Psychotherapy: Guidelines and Suggestions for Therapists. In Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy, 4th Edition. San Diego: Elsevier; 2015; 141-155.

Friedmann E, Locker BZ, Lockwood R. Perception of Animals and Cardiovascular Responses During Verbalization With an Animal Present. Anthrozoos. 1993; 6(2): 115-34.

Gee NR, Mueller MK. A Systematic Review of Research on Pet Ownership and Animal Interactions Among Older Adults. Anthrozoös. 2019; 32(2): 183-207.

Gee NR, Rodriguez KE, Fine AH, Trammell JP. Dogs Supporting Human Health and Well-Being: A Biopsychosocial Approach. Front Vet Sci. 2021; 8: 630465.

Gee NR, Townsend L, Findling RL, eds. The Role of Companion Animals in the Treatment of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub; 2023.

Havener L, Gentes L, Thaler B, et al.: The Effects Of A Companion Animal On Distress In Children Undergoing Dental Procedures. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs 2001; 24(2): 137-52.

Jones MG, Rice SM, Cotton SM: Incorporating Animal-Assisted Therapy In Mental Health Treatments For Adolescents: A Systematic Review Of Canine Assisted Psychotherapy. PloS ONE. 2019; 14(1): e0210761.

Megna, M. Pet Ownership Statistics 2023. Forbes Advisor. https://tinyurl.com/3d2ac4sf.

Meehan, M., Massavelli, B., Pachana, N. Using Attachment Theory and Social Support Theory to Examine and Measure Pets as Sources of Social Support and Attachment Figures. Anthrozoös. 2017; 30(2), 273-289.

Pendry P, Carr, AM, Gee, NR, & Vandagriff, JL: Randomized Trial Examining Effects of Animal Assisted Intervention snd Stress Related Symptoms on College Students’ Learning snd Study Skills. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17: 1909-1926.

Purewal R, Christley R, Kordas K, Joinson C, Meints K, Gee N, Westgarth C. Companion Animals And Child/Adolescent Development: A Systematic Review of The Evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017; 14(3): 234.