Guidance on How to Diagnose and Treat Psychotropic Drug Reaction Known as DRESS

Abstract

DRESS syndrome has a broad spectrum of clinical features and can be life threatening. Early identification and treatment are essential.

You receive a telephone call from an outpatient—a 45-year-old attorney in treatment for major depressive disorder—who is concerned about a new skin rash on her back that appears to be spreading. The patient was prescribed aripiprazole three weeks earlier as an adjunct to duloxetine for persistent depression. She takes no other medications. On further questioning, the patient reports a flulike illness with fever, muscle aches, and diarrhea one week previously, with resolution of those symptoms. Among the differential diagnoses is DRESS syndrome.

The DRESS syndrome—drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms—is a delayed-onset drug reaction characterized by a severe drug rash associated with fever, lymphadenopathy, internal organ involvement, and hematologic abnormalities. Internal organs affected include the liver, kidneys, lungs, heart, and pancreas, and brain involvement takes the form of encephalitis and/or meningitis. The syndrome has a 10% or greater mortality rate, even with early recognition and treatment. DRESS has generally been underrecognized in psychiatry, even though many of the implicated drugs are psychotropics. The pathogenesis of DRESS is thought to involve an interaction of specific HLA haplotypes, viral infection or reactivation (with HHV-6 herpesvirus, Epstein-Barr virus, or cytomegalovirus), and medication.

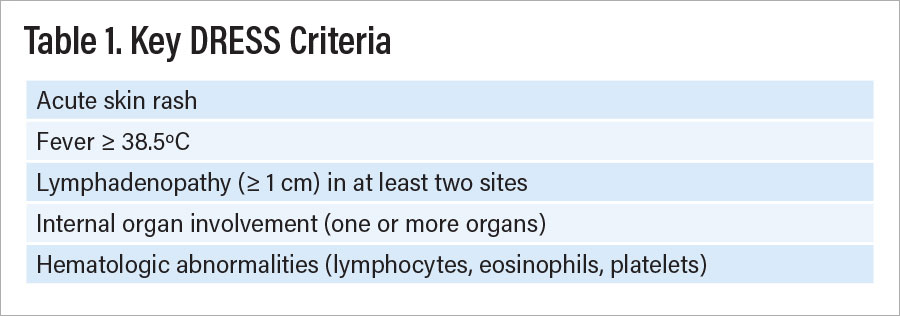

Table 1.

The presentation of DRESS is variable, with a range of signs and symptoms that may present sequentially rather than simultaneously such that many cases may go undetected. Key criteria are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1: The photo shows a characteristic rash of a patient with DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms).

The DRESS rash typically appears two to eight weeks after the drug is initiated, sometimes earlier with drug re-challenges. The rash is classically described as morbilliform (measles-like), as shown in Figure 1, but many other presentations are seen, including urticarial, targetoid (erythema multiforme-like), and pustular. The rash spreads rapidly to involve more than 50% of the body. In about one-third of cases, gross facial edema accompanies the rash, and this suggests more serious disease. Lymphadenopathy typically involves more than one node, with enlargement often 1 cm or more.

The internal organ most affected in DRESS is the liver, with presenting features of hepatitis, jaundice, or asymptomatic transaminitis. The pattern of injury can be hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed. Kidney involvement takes the form of acute interstitial nephritis with proteinuria, hematuria, and sterile pyuria. Pulmonary manifestations include pneumonia, effusions, nodules, and acute respiratory distress. Myocarditis associated with DRESS may develop in association with the rash or as a late manifestation, up to four months after the first symptoms occur. Pancreatic involvement can be acute or appear late and may involve endocrine more than exocrine functions. Hematologic signs include eosinophilia, thrombocytopenia, leukocytosis, lymphocytopenia, and atypical lymphocytes.

Several autoimmune conditions may develop as late-appearing sequelae of DRESS. The most common is autoimmune thyroiditis, which may occur at any time from several weeks to three years after initial symptoms. Other syndromes include systemic lupus erythematosus, diabetes mellitus type 1, and autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

When DRESS is suspected, a formal diagnosis can be made using an algorithm such as that developed by the European Registry of Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (RegiSCAR). Scoring yields a diagnosis of possible, probable, or definite DRESS. Formes frustes presentations are possible. The RegiSCAR with scoring is reproduced in a paper in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences by Yung-Tsu Cho, M.D. Signs and symptoms of DRESS may persist for weeks to months after the offending drug is withdrawn. The syndrome can recur, and recurrence is associated with a higher mortality rate than the initial episode.

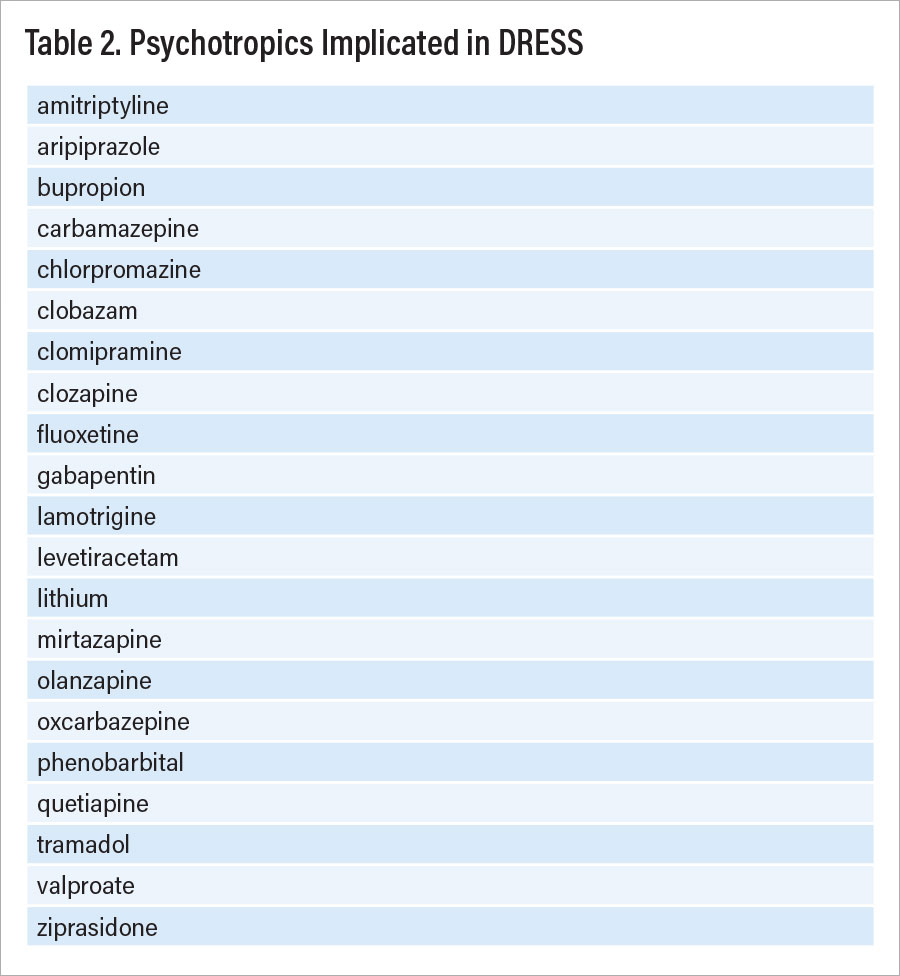

Table 2.

Drugs implicated in DRESS include a range of antibiotics, antivirals, anticonvulsants, analgesics, and psychotropics. Individual drugs such as allopurinol are often involved. Table 2 lists psychotropic medications reported with DRESS. Among psychotropics, anticonvulsants are most often implicated, with carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and valproate involved most often, although this could reflect more frequent use of these drugs. Laboratory testing for patients presenting with DRESS symptoms includes the following:

CBC with differential and platelets (including search for atypical lymphocytes)

C-reactive protein

Liver function tests

Creatinine, glucose, calcium

Urinalysis for protein, cells

Creatine kinase, troponin

ECG

Other tests are recommended by specialists to evaluate specific internal organ involvement. In addition, PCR testing for herpesvirus 6 and other viruses may be suggested. For more complex cases, patch tests and lymphocytic transformation tests can be used to identify specific drugs implicated.

When DRESS is diagnosed, the offending drug must be discontinued and not restarted. Supportive care should be initiated, and this may require admission to a specialized ICU or burn unit when erythroderma or extensive exfoliative dermatitis are present. Systemic glucocorticoids are a mainstay of treatment in all but the mildest cases, which can be treated with high-potency topical glucocorticoids. Detection and monitoring of visceral organ involvement is critical and should involve appropriate medical specialists. ■