Special Report: Opioid Use Disorder—Treatment in an Ever-Changing Crisis

Abstract

Faced with the loss of more than 100,000 Americans to drug overdose each year, the federal government has expanded access to an increasing number of medications to treat opioid use disorder, thus providing psychiatrists with a broad array of treatment options that one does not need to be an addiction specialist to offer.

Helping patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) is a core responsibility of psychiatry, but widespread treatment of OUD by our profession has been hampered by a complex legal patchwork of state and federal regulations. This has led to the creation of specialty clinics for providing medications for OUD, reducing opportunities for psychiatrists to provide safe, effective medical therapy to their patients and hindering access to treatment for those who seek it. In an era of unprecedented mortality and near-death resulting from a flood of illicit synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, it is critical that psychiatrists take part in providing treatment for patients with OUD and ensure that interventions that reduce harm to patients are widely available. Supporting this goal are numerous changes to federal laws governing the provision of OUD treatment and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) priority approval of new medications for OUD.

Recent Trends in Opioid-Related Deaths and Near-Deaths

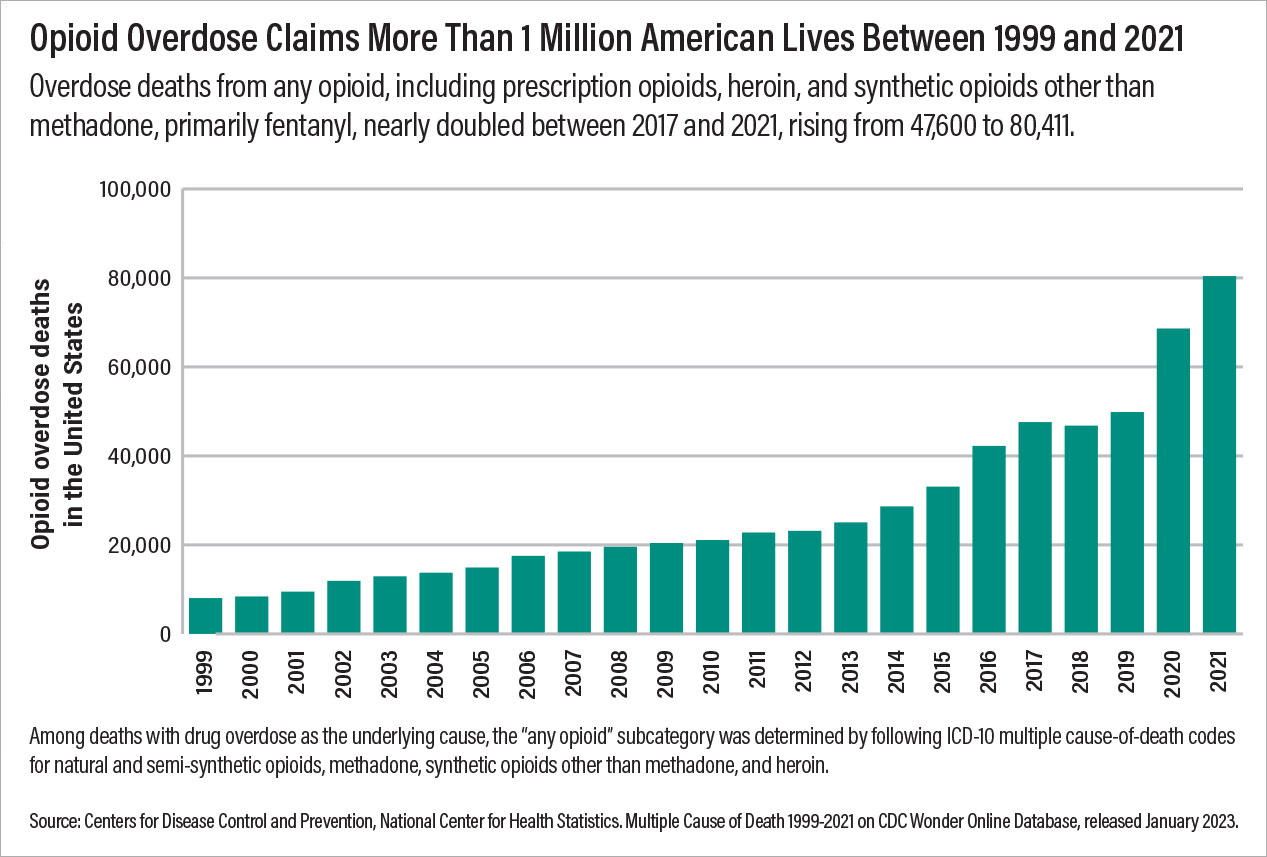

In the United States, over 1 million people have died from drug overdose in the last 25 years. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), annual overdose deaths have more than doubled in the last decade to over 106,000 in 2021. In 2021, opioids were involved in approximately 75% of drug overdose deaths, driven by the wide availability of potent, synthetic opioids such as fentanyl. Deaths involving heroin have decreased in recent years as fentanyl has displaced heroin in the illicit opioid supply. Many opioid overdose deaths involve co-exposure to stimulants such as methamphetamine. Methamphetamine and other stimulants may now be contaminated with fentanyl. In addition, fentanyl is also sometimes contained within “pressed” pills that appear similar to prescription medications, such as oxycodone or alprazolam. This means that individuals with occasional or exploratory use of illicit substances may be at risk of fentanyl overdoses.

Opioid overdose deaths vary by demographic. In recent years, approximately 70% of opioid overdose deaths have occurred in males. In 2021, opioid overdose rates were 38.0 among non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native individuals and 34.7 among non-Hispanic Black individuals, compared with 26.9 per 100,000 among non-Hispanic White individuals. Although there is some geographic variation, overdose deaths increased in all but three states from 2019 to 2020, and most states had increases of over 30%.

Opioid use disorder is highly comorbid with other psychiatric illnesses. According to the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, among people who reported OUD, 60% also reported having a mental illness. Of those who reported having both OUD and mental illness, one-third reported having a serious mental illness. Roughly 25% of people with OUD have had a major depressive episode in the last year.

Providing effective psychiatric care to patients with comorbid OUD and psychiatric conditions involves treatment for substance use. Engaging patients in treatment for OUD also provides an opportunity to identify needle-borne illnesses, including HIV and hepatitis C (HCV). Ensuring that all patients have access to care, reducing barriers to treatment, and providing care in ways that are understandable and acceptable to all patients are critical. Every psychiatrist can provide care for patients suffering from OUD. Recent changes to federal laws and the approval of new medications for OUD provide us with new tools in our shared goal of providing comprehensive mental health care to our patients.

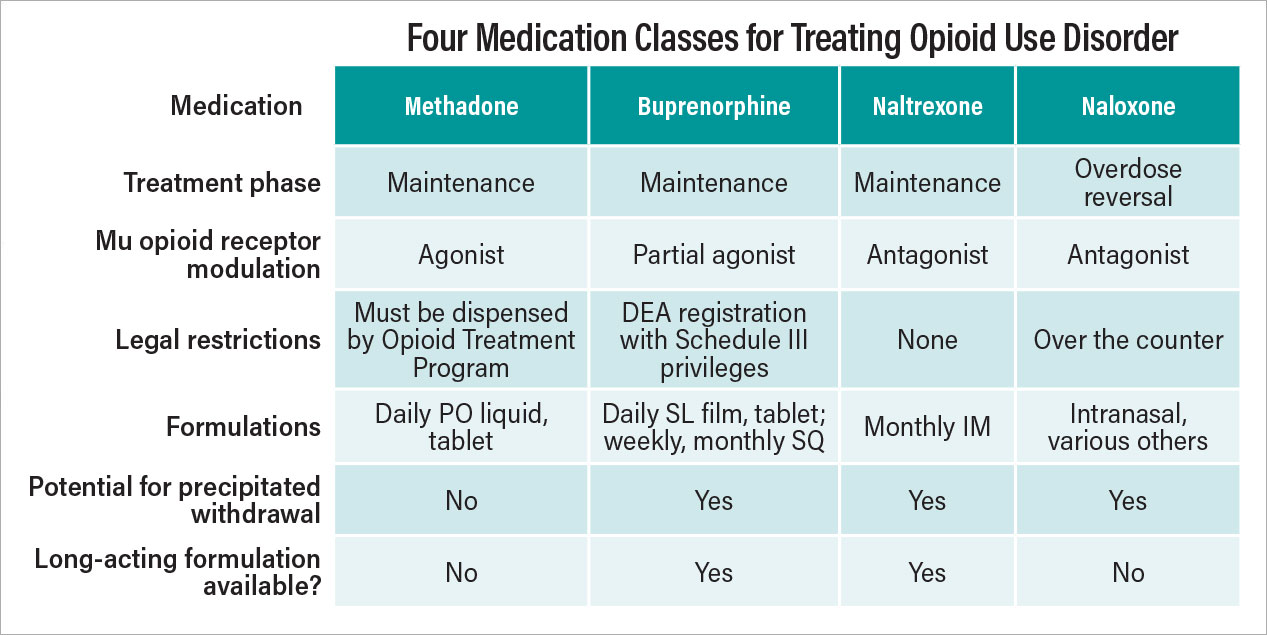

The X-waiver Has Been Xed

Buprenorphine is a semisynthetic opioid with high affinity for the mu-opioid receptor. Unlike most opioids, buprenorphine exhibits a ceiling effect on both euphoria and respiratory depression reducing the potential for fatal overdose with the medication. It also has a longer half-life than many other opioids, allowing longer periods of time without withdrawal symptoms. These properties make it an excellent medication for treating opioid dependence, and various buprenorphine formulations are FDA approved for treating pain or OUD.

The Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 placed restrictions on the prescription of buprenorphine for OUD, requiring those who wish to prescribe it to take an eight-hour training course, register for a unique Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) number known as an “X-waiver,” and report the number of patients they treat each year. The law also capped the number of patients that each waivered prescriber could manage.

To reduce barriers to buprenorphine for OUD treatment, Congress eliminated the X-waiver requirement as of December 29, 2022. The Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment Act removed the previously mandated training, registration, patient cap, and reporting requirements. Now, from a federal perspective, any health professional (except veterinarians) who holds a DEA registration with Schedule III authority can prescribe buprenorphine for OUD where state law allows. There may be additional requirements at the state level, but the federal X-waiver is no longer required.

In lieu of the X-waiver, as of June 27, 2023, all health professionals renewing or applying for a Schedule II-V DEA license are required to attest to completing eight hours of treatment and management of patients with opioid or other substance use disorders. This may help address gaps in medical education about OUD treatments. For example, only a minority of psychiatry residency programs provide dedicated training in office-based OUD treatment with buprenorphine, despite a near-universal perspective of residency directors that this is an important training direction. Widening the available pool of health professionals who may prescribe buprenorphine should increase the office-based identification and management of patients using buprenorphine and reduce the stigma of receiving treatment for OUD.

Increasing the provider pool is a critical step in the widespread availability of buprenorphine for OUD, but additional barriers to universal access remain. Higher out-of-pocket costs are associated with buprenorphine discontinuation, and although Medicare has eliminated prior authorization requirements for buprenorphine products, most state Medicaid programs restrict the free prescription of buprenorphine, either through prior authorization, adjunct treatment requirements, or maximum daily limits. Beyond sublingual formulations of buprenorphine, long-acting injectables are not consistently covered by Medicaid formularies or private insurance.

Telehealth Buprenorphine and Prescribed Methadone

Telepsychiatry has the potential to further reduce barriers to treatment access and expand treatment opportunities to patients in rural locations or with limited transportation. The Ryan Haight Online Consumer Protection Act of 2008 has governed the prescription of opioids, including buprenorphine, by telehealth. In an effort to combat online “pill mills” that prescribe opioids outside of the course of regular care, the act requires “at least one in-person medical evaluation of a patient” before the initiation of an opioid, including buprenorphine treatment for OUD. On March 16, 2020, the DEA announced that it was suspending the requirement for an in-person evaluation of patients with OUD in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: Patients could be started on buprenorphine after only a telehealth encounter. This exception was intended to sunset at the end of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency, but it is now under consideration as a rule change by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and the DEA. The full set of telehealth exceptions enabling remote buprenorphine prescriptions for both new telehealth patient-health professional relationships and existing ones has now been extended through December 31, 2024. This second extension collapses into a single date the separate rules for new and established patients that had been set out in the first rule extension.

In parallel, early efforts are underway in Congress to change prescribing rules for methadone, a full opioid receptor agonist that is FDA approved and widely used for treating OUD. Its long but variable half-life requires careful management during the titration phase of treatment. Federal law and regulations require that methadone for OUD to generally be dispensed only from federally regulated Opioid Treatment Programs (OTPs). This requirement creates a highly controlled environment for methadone dispensing and reduces patient access. According to a study in JAMA Psychiatry in 2020, the estimated average travel time to a methadone clinic in the United States was more than 20 minutes one way, and 5% of the U.S. population had a drive time of greater than 60 minutes to the nearest OTP. Rural areas of the country had more limited access to these clinics, and certain areas had very limited access. For example, there were no OTPs in the entire state of Wyoming.

SAMHSA loosened rules for methadone prescribing during the COVID-19 public health emergency. On March 16, 2020, OTPs were informed that individual states were able to request blanket exceptions so that stable patients could receive a 28-day take-home supply of methadone and less stable patients could receive a 14-day take-home supply. Since then, SAMHSA has concluded that the benefit of liberalized methadone take-home dosing outweighs the increased potential for diversion and misuse. In states that concur, SAMHSA has extended the exemptions to federal regulation allowing increased take-home dosing flexibility. This new exemption allows patients to receive up to a seven-day take-home supply within their first two weeks in an OTP, up to a 14-day take-home supply in their next 15 days in the clinic, and up to a 28-day take-home supply at a time thereafter. This exemption will remain in place until whichever occurs sooner between (1) one year and the end of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency or (2) the publication of a new federal rule revising the federal methadone regulations.

Finally, a bipartisan effort by Congress, the Modernizing Opioid Treatment Access Act, is now under consideration. If passed, this legislation would enable pharmacy dispensing of methadone for the treatment of OUD as prescribed by board-certified addiction specialists, rather than limiting dispensing to OTPs. As currently proposed, this legislation would require a provider registration process and would enable telehealth methadone maintenance for some patients.

Opioid Overdose Reversal Agents

Most opioid overdoses occur outside of a medical setting and immediate intervention can be the difference between life and death. Community-based, immediate response by civilian bystanders is therefore critical to reducing overdose mortality. Intranasal naloxone, typically available as a single-use, 4 mg dose, represents the mainstay of treatment. As nearly half of opioid overdose deaths have potential bystanders present, improving access to naloxone for patients, family, friends, and first responders can save lives.

In March 2023, the FDA approved naloxone nasal spray for over-the-counter (OTC) sale without a prescription, and the first OTC naloxone sprays became available at pharmacies in August. However, OTC naloxone carries a price tag of around $45 for a package of two nasal sprays. (Sometimes both sprays are needed to reverse an opioid overdose.) It is critical to share with patients that they are unlikely to be able to give themselves naloxone. Patients should involve individuals who would likely be bystanders in case the patient has an overdose, such as family, friends, roommates, and neighbors. These individuals should be taught how to administer naloxone, be able to provide CPR to the patient if necessary, and be willing to call 911 after administering naloxone.

With the increasing prevalence and use of illicit synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, additional medication options for the treatment of opioid overdose are needed. The FDA recently approved nalmefene nasal spray as a prescription medication for opioid overdose reversal. Nalmefene is a molecule closely related to naloxone, but with a substantially longer half-life.

Harm Reduction Tools and Financing

A core tenant of treatment for any substance use disorder is reducing the harms experienced by patients in the course of substance use. Harm reduction is an evidence-based approach that is effective in reducing substance-related morbidity and mortality and a key pillar in the Federal Overdose Prevention Strategy. Needle exchanges to reduce the transmission of human immunodeficiency virus, HCV, and other diseases transmitted by shared needles among those who use intravenous drugs is an example of an effective, low-cost harm reduction approach.

In addition to these more established harm reduction strategies, there has recently been increasing interest in the use of fentanyl test strips (single-use lateral flow immunoassays similar to home COVID and pregnancy tests) to reduce accidental exposure to fentanyl. The individual puts some of the substance in water and dips the test strip in the water, and the test strip will reveal whether—but not how much—fentanyl is in a substance. It is critical to note that fentanyl may not be evenly distributed throughout a substance (such as a pressed pill) and so the absence of a positive fentanyl testing strip result does not guarantee safety.

As of April 7, 2021, federal grants from SAMHSA and the CDC for relevant programs can be used to purchase fentanyl test strips for community distribution. Despite the support of the federal government and the critical need to provide point-of-use information to people who use substances, many states still classify test strips and needle supplies as drug paraphernalia, a holdover from the “War on Drugs.” This makes the possession of these items illegal and impedes organized efforts to distribute them.

Although fentanyl test strips provide information to people who use substances and to law enforcement officers regarding the presence of fentanyl in a substance, there remains a diagnostic gap in screening individuals for substance use. There is now a single point-of-care, FDA-approved test product for urine fentanyl testing, but it requires a stand-alone device that is not CLIA waived. There is no FDA-approved point-of-care stand-alone test for fentanyl approved for home use and standard drug screening panels may not detect widely used synthetic and semisynthetic opioids such as tramadol, methadone, and fentanyl. This limits the majority of health professionals to sending out a laboratory test for mass spectrometry urine analysis, which has a multiday turnaround time.

Beyond fentanyl, the recent trend of mixing xylazine (“tranq”) into illicit opioids has created a new challenge for both individuals who use opioids and health professionals who treat OUD. The same manufacturers that produce fentanyl testing strips now have xylazine testing strips.

You Can—And Should—Help Patients with OUD

The opioid crisis has taken a number of forms over the last few decades: prescription opioids, heroin, and now fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. Opioid use disorder and the tragedy of overdose have cut across all demographics, and many psychiatrists will have an opportunity to provide potentially lifesaving interventions for patients who have OUD. The good news is that there are more options than ever to provide this care. A changing federal perspective on OUD treatment has permitted more health professionals to prescribe buprenorphine, methadone take-home flexibilities have made this medication a viable option for more patients, and naloxone is available over the counter. Telehealth enables health professionals to treat patients who live far with limited mobility or who live in rural areas. Harm-reduction options enable patients to reduce the potential harm of opioid use.

The opioid crisis has been devastating to our patients, and it is important that psychiatrists learn about the interventions that can help patients who have OUD. All health care providers—not just addiction psychiatrists—can learn to use the effective tools that are available for the management of OUD and make a difference in their patients’ lives. ■

This information is provided as general background and should not be construed as legal or clinical advice. Clinicians should consult with their jurisdiction’s laws, regulations, and clinical practice guidelines when providing OUD related treatment.

Resources for Psychiatrists

APA Resources

APA Blogs

Animated Explainer Video

Other Resources

DEA list of questions for health professionals who wish to prescribe buprenorphine

Resources from SAMHSA for health professionals interested in prescribing buprenorphine for their patients

Report References

Monthly Patient Volumes of Buprenorphine-Waivered Clinicians in the U.S.

Thematic Analysis of State Medicaid Buprenorphine Prior Authorization Requirements

Comparison of Driving Times to Opioid Treatment Programs and Pharmacies in the U.S.

Toxicosurveillance of Novel Opioids: Just Screening Tests May Not Be Enough