Movement Emerges to Include Green Space as a Social Determinant of Mental Health

Abstract

A rich and growing literature shows that immersion in nature and exposure to green space has a measurable impact on health and mental health. This is the first in a three-part series.

On a recent Saturday in Rock Creek Park in Washington D.C., Sarah Dewitt, a certified forest therapy guide, led a handful of people in the ancient Japanese practice of “Shinrin-yoku”—forest breathing or forest bathing.

“Forest bathing is a very slow and mindful walk in nature,” Dewitt told Psychiatric News. “It starts with a warm-up in which I invite participants to tune into each of their senses one at a time. Then I might invite them to wander out in the woods and pay close attention to all the things that are in motion.”

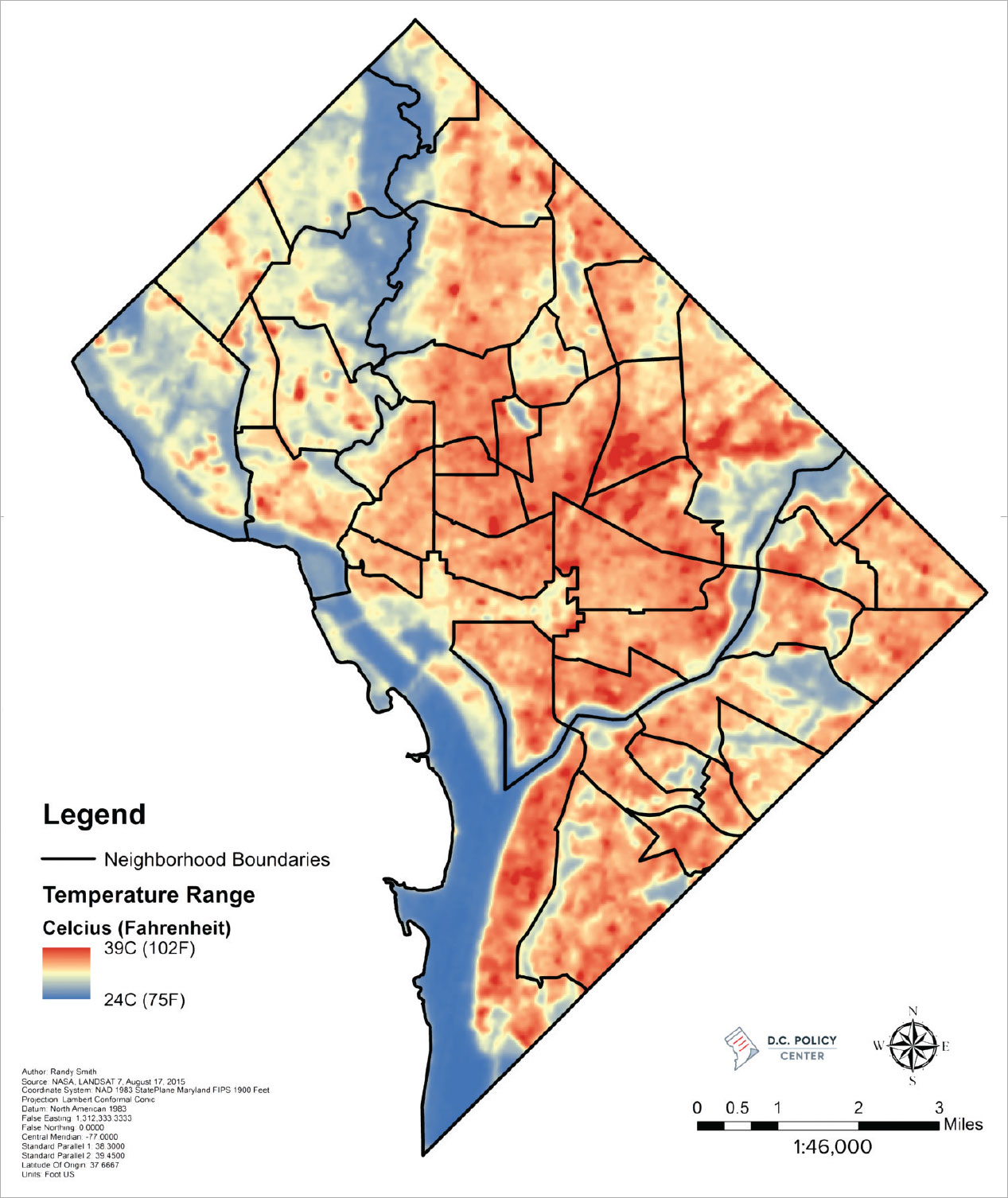

This heat map displays the range of temperatures in Washington, D.C., on August 17, 2015. The blue areas, including the Potomac River and also Rock Creek Park in the upper Northwest section of the city, are 15 degrees cooler than the hottest parts of the city.

It is customary to end a forest bathing walk with a tea service. This offers participants a chance to “taste” the forest, after tuning into their other four senses during the walk: sight, sound, smell, and touch. Traditionally a small amount of tea is poured back to the land as a gesture of gratitude and reciprocity before participants taste the tea and share reflections of their experience in the forest, Dewitt said.

In a city overheated in more ways than one, forest bathing is a welcome retreat, and Rock Creek Park is an oasis—33 miles of meandering creek and 1,800 acres of forestland administered by the National Park Service (NPS). The park serves as the city’s heart and lungs: On the hottest summer days it may be as much as 15 degrees cooler in the park than in the hottest parts of the city (see map). And it serves as an important carbon capture, storing more than 100,000 tons of carbon above ground, according to Rock Creek Conservancy, a nonprofit partner to the NPS dedicated to preserving the park.

To follow the creek and wander the forest paths at any time of year is to experience a little bit of what the poet Mary Oliver meant when she wrote: “It is a serious thing just to be alive on this fresh morning in this broken world.”

But forest bathing is more than an esoteric exercise of the spiritually or aesthetically inclined. There is a rich and growing literature showing that immersion in nature and exposure to green space has a measurable impact on health and mental health, and there is an emerging movement in some quarters of medicine to incorporate this research into clinical practice.

Still, the concept of proximity to greenspace as a social determinant of health and mental health—similar to access to food, housing, and health care—remains still slightly out of the mainstream, at least in the United States.

“In psychiatry we tout exercise, collaboration, and connection as important to mental health, but not enough people are talking yet about green space as a social determinant of health,” said child and adolescent psychiatrist Sara Anderson, M.D., M.P.H., a member of the APA Caucus on Social Determinants of Mental Health and the APA Caucus on Climate Change.

Anderson said she works with children and teenagers with significant anxiety about being outdoors, a fear exacerbated by COVID-19. And public green space is very inequitably distributed: Children in lower socioeconomic neighborhoods are far less likely to have access. “We talk about adverse childhood experiences, but we don’t talk about the environment and how that may contribute to or undermine resilience.”

Anderson asked: “How can we create a passion to connect people to nature as an adjunct to developing connection and a locus of control in a world where we all feel out of control?”

Green Space Affects Population Health

Rock Creek Park’s nearly 1,800 acres of forest are the heart and lungs of the Washington, D.C., region, serving as a climate oasis and storing 100,000 tons of carbon above ground.

If green space as something to incorporate into treatment has not quite made it to center stage, there is no lack at all of research on the subject.

“There is a strong and growing body of research showing that exposure to green space is related to better mental health, better cognition, higher levels of physical activity, lower cardiovascular disease, and lower mortality,” said Peter James, Sc.D., an associate professor of environmental health at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and an associate professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School.

“The strongest lines of research are randomized trials showing short-term improvements in mood and cognition after exposure to nature because they are experiments designed in such a way as to control for potential confounders.”

Some of this research goes back decades. A foundational 1984 study by R.S. Ulrich in Science found that 23 surgical patients assigned to rooms with windows looking out on a natural scene had shorter postoperative hospital stays, received fewer negative evaluative comments in nurses’ notes, and took fewer potent analgesics than 23 matched patients in similar rooms with windows facing a brick wall.

James has specialized in observational epidemiology using satellite images and Google street views to connect geographic areas of green space to population health and mental health outcomes. “There is a really robust literature showing that people who live in greener areas have better mental health and lower depression and anxiety, even adjusting for lots of other factors,” he told Psychiatric News.

He cited a remarkable 2019 study from Denmark in PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences). Researchers used longitudinal health data from more than 900,000 Danish citizens coupled with high-resolution satellite images to show that greater exposure to green space during childhood was associated with lower risk of a wide spectrum of psychiatric disorders later in life. Risk for subsequent mental illness among those who lived with the lowest level of green space during childhood was up to 55% higher across various disorders compared with those who lived with the highest level of green space. The association remained even after adjusting for urbanization, socioeconomic factors, parental history of mental illness, and parental age.

Greenspace Integral to City Infrastructure

How might exposure to green space influence health? The dominant hypothesis is that of “biophilia”—a love of living things—a term coined by the naturalist E.O. Wilson. As James explained it, “We like being in nature because we are nature, we evolved in nature. This is the setting we were meant to be in. So, when we are stressed, we recover best in natural settings.”

“Not enough people are talking yet about green space as a social determinant of health,” said Sara Anderson, M.D., M.P.H.

Anyone who takes a casual stroll in the woods after an argument can probably confirm this. But if the connection between nature and health is so intuitive, why is it not more widely adopted in clinical practice? Anderson said a principal obstacle is the lack of succinct and shared terminology of what green space means. “It is unclear what the right ‘dose’ is or what the type of environment should be that makes a difference—city park, forest, small backyard, plants in your home,” she said.

Answering that is key, said James. “What is the active ingredient in nature?” he asked. “What is the specific component of nature that influences our health? That’s a complex question, but it’s not just an academic exercise; it’s crucial to determining what an intervention would look like and how we would administer it.”

More generally, he believes that kind of evidence of how exposure to green space impacts individual and population health would help to transform the way we think about public infrastructure, with benefits for a warming planet.

This means advocating for the planting of trees and the creation of small, local parks—not just maintenance of the grand national parks for which the U.S. is famous. “There is a huge win-win to the planting of trees in cities,” he said. “We can sequester carbon, cool urban areas, decrease health disparities, and improve health outcomes.”

James added, “The shift we need is to view landscape architecture and greenspace as a fundamental component of city infrastructure for everyone, not a perk or amenity for the wealthy.” ■