Mental Health Services Conference Kicks Off With Presidential Session on Addiction

Abstract

The neurobiology of addiction has evolved from a focus on the “war” between pleasure-reward pathways in the brain that have been hijacked by substance use and the frontal lobes.

Understanding of the causes of substance use disorder (SUD) and behavioral addictions has come a long way since the 1980s, when addiction was recognized as a biopsychosocial illness, said APA President Petros Levounis M.D., M.A., at the Opening Session of APA’s Mental Health Services Conference. His presentation included a historical perspective of addiction and a discussion of a newer, more modern neurobiological framework that describes how addiction changes the circuitry of the brain.

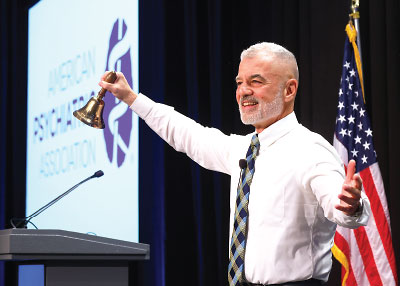

APA President Petros Levounis, M.D., M.A., performs the traditional bell-ringing ceremony to open the Mental Health Services Conference (MHSC). The bell was presented in 1968 to Daniel Blain, M.D., who convened the first Mental Hospital Institute (the forerunner of the MHSC) in 1949 to discuss problems in mental hospitals and to work out solutions. Blain was APA’s first medical director.

Levounis described SUD and behavioral addictions as a complex interplay between psychological forces and neurobiological forces. He said that whereas it was once thought that individuals use substances to get high, escape, or self-medicate underlying, untreated psychiatric disorders like depression and anxiety, the psychological reasons for substance use are more nuanced and complex, such as using substances to enhance academic, athletic, or sexual performance.

Repeated substance use or repeated behaviors can also set the stage for SUD, Levounis said.

“We learned that lesson from the opioid epidemic, where the majority of people who got addicted to prescription opioids back in the late 1990s and early 2000s were [people who were injured], went to their doctors, and were prescribed massive amounts of opioids,” Levounis said. “So it’s use of the drug that increases vulnerability and can lead to addiction.”

He described how modern concepts of the neurobiology of addiction have evolved to focus on the “war” between pleasure-reward pathways in the brain that have been hijacked by substance use and the frontal lobes, which are responsible for rational thinking.

“The next time you have [a patient with SUD] in front of you, visualize in your head how strong are their hijacked pleasure-reward pathways versus how strong are their frontal lobes,” he said. “If the pleasure-reward pathways [are stronger], the person will relapse. If the frontal lobes are stronger, the person will be in recovery.”

Levounis also discussed the “anti-reward” pathways in the brain. He explained that when these pathways are activated, they produce irritability, annoyance, misery, restlessness, and pain. “What happens is that the addiction morphs from primarily pleasure and reward to a desperate attempt to avoid pain,” he said.

Levounis described another component of the neurobiology of addiction, interoception, which is the process by which the mind senses internal signals from the body such as hunger or a rapid heartbeat. These signals can also include cravings, such as when people who smoke crave a cigarette. Levounis described research wherein people who smoked cigarettes and had a stroke that affected the parts of the brain responsible for interoception no longer felt the urge to smoke. ■