Special Report: Positive Psychiatry Shines Light on Patients’ Strengths, Wisdom

Abstract

Social connectedness is a vital positive psychosocial determinant of health, but one that has not until recently received the attention it deserves. In November 2023, the World Health Organization called loneliness a pressing health threat and made addressing it a global priority.

When physicians see a new patient, the first question they ask is, “What brings you here?” Then come questions about precipitating factors—what physical, psychological, or social events precipitated the illness or the relapse? This is followed by questions about risk factors: Do you smoke, drink, use drugs? Collecting and evaluating such information is an essential part of making a diagnosis.

But how often do we ask patients about the positive aspects of their lives? “What are your strengths? What do you like about yourself? What things do you enjoy doing? What makes you happy? Who are the people you like to spend time with? What makes them your best friends? What do you think prevented a relapse of your depression during the last five years?”

These often-unasked questions are essential for understanding the patient as a whole person and for developing therapies in which a patient will want to engage. The best way to promote adherence is to tailor treatment to patients’ strengths, not just their impairments.

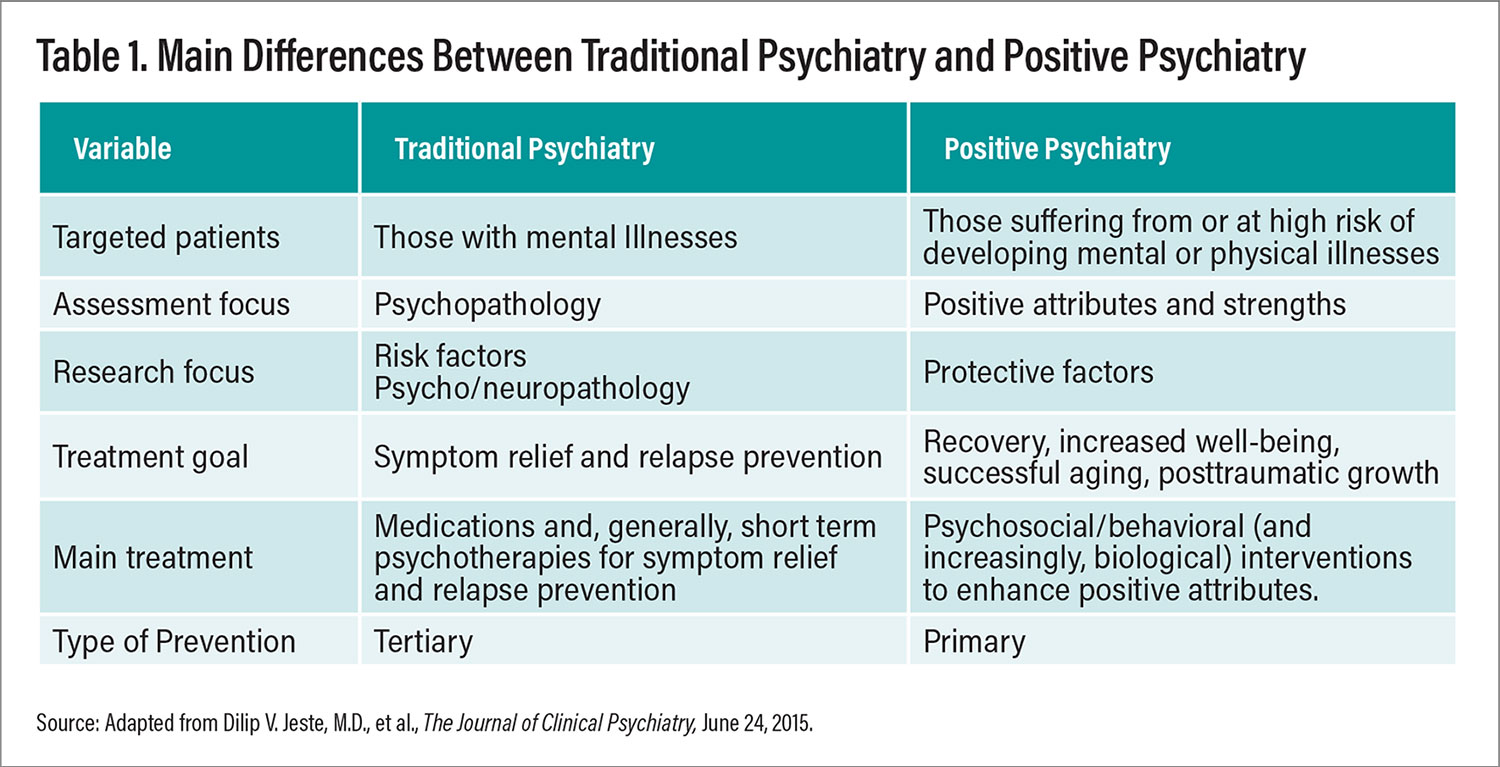

That is positive psychiatry, the science and practice of psychiatry that focuses on the study and promotion of mental health and well-being through enhancement of positive psychosocial factors. This positive focus is consistent with the recently proposed concept of “whole health” outlined in the recent report of the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, which describes whole health as the physical, behavioral, spiritual, and socioeconomic well-being of individuals, families, and communities. Whole health care is an interprofessional, team-based approach anchored in trusted relationships.

In the early 20th century, the psychologist/physician William James proposed the construct of a “mind-cure,” the purported restorative powers of positive emotions and beliefs. Fifty years later, the mind cure was expanded by Abraham Maslow and colleagues and became what we know as humanistic psychology. Maslow contended that measuring and cultivating overall health and creativity was the best approach to improving outcomes in people with mental illnesses. In the late 1990s, Martin Seligman, Ph.D., and colleagues advanced the positive psychology movement, which aims to maximize well-being through increased attention to positive factors.

Positive psychiatry extends a biopsychosocial perspective to wellness in individuals afflicted with mental illnesses. As APA president in 2013, my main task was to oversee the publication of DSM-5, certainly one of APA’s most valuable contributions to psychiatry. The DSM is a catalogue of mental disorders that are present in about 20% of the population—but 100% of people have mental health including some positive traits. Positive psychiatry is an approach to mental health that can speak to everyone with or without a psychiatric disorder.

The following are some elements of positive psychosocial health.

Resilience

Table 1. Main Differences Between Traditional Psychiatry and Positive Psychiatry

Resilience is a trait or a process that describes the ability to recover from adverse situations and to adapt in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or other sources of major stress. Commonly used measures of resilience include self-report-based scales such as the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale and the Grit Scale. Considerable work has been published on the biology of resilience including genomics and cellular and molecular mechanisms. Numerous studies have reported resilience to be associated with higher educational attainment, marriage, emotional stability, social connectedness, community integration, and purpose in life, as well as decreases in all-cause mortality and lower rates of depression. In a study of adults with schizophrenia and healthy comparison participants, the current level of resilience appeared to serve a protective role against the negative mental and physical health effects of early-life adversities. In contrast to adults with schizophrenia who had lower levels of resilience, those with higher resilience in adulthood reported significantly fewer negative effects of childhood traumas, and their metabolic biomarker levels were comparable to those of healthy participants. This suggests that resilience could be a buffer against early psychosocial stress in schizophrenia.

Wisdom

Wisdom is a personality trait composed of several specific components: prosocial attitudes and behaviors (empathy and compassion), self-reflection, emotional regulation, acceptance of uncertainty and diversity of perspectives, social advising, rational decision-making, and spirituality. Commonly used self-report-based scales for assessing wisdom with good psychometric properties include the San Diego Wisdom Scale. Across the lifespan, wisdom is associated with positive outcomes including better overall physical and mental health, happiness, and lower levels of depression and greater life satisfaction, subjective well-being, and resilience. A number of cross-sectional studies have reported that older adults score higher than younger adults on several components of wisdom, especially pro-social behaviors, self-reflection, and emotional regulation, and recent clinical and biological studies have reported a strong inverse relationship between loneliness and wisdom, especially its compassion component. These suggest potential use of individual- and societal-level interventions to enhance compassion and other components of wisdom to reduce loneliness and improve well-being.

Meaning in life

Meaning or purpose in life is the psychological perception of one’s own life and activities, the value and importance attributed to them, and the degree to which they generate a sense of meaning or purpose. Validated instruments to assess meaning in life include the Meaning in Life Questionnaire, which has two components: presence of meaning and search for meaning in life. Multiple research studies have demonstrated a strong link between purpose and better physical, mental, and overall health outcomes across the entire adult lifespan. Meaning in life may also be a protective factor against suicide.

Religiosity and spirituality

Religion is defined as an institutionalized system of beliefs in a superhuman power like a God or gods. Spirituality is usually more personal than institutional, though there can be an overlap between religiosity and spirituality. The Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality is one of the most comprehensive instruments used in this type of research. According to a 2012 study of schizophrenia and related disorders using semi-structured interviews, published in The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, higher levels of religiosity and spirituality were associated with increased hope, purpose, meaning; attenuated psychotic symptoms; more positive social interactions; and lower risk of suicide. A three-year follow-up showed that participants who engaged in healthy religious coping strategies and who valued spirituality experienced lower degrees of negative symptoms and improved interpersonal functioning and quality of life.

‘Successful Aging’ Not an Oxymoron!

Chronological aging is associated with increases in both physical and cognitive ailments. But a wealth of neuroscience research during the past three decades has demonstrated a neurobiological basis for successful aging in active older adults. Contrary to traditional beliefs, neuroplasticity continues into old age (albeit to a lesser degree than in younger individuals), allowing new learning and adaptation in the context of appropriate social and environmental stimulation. Mechanisms underlying plasticity in older adults include neural compensation for age-related decline through the recruitment of additional brain circuits, dendritic arborization, and synapse proliferation; increased vascularity; and a limited degree of subcortical neurogenesis.

Successful aging is seen in some people with serious mental illnesses. Studies have found that relative to their younger counterparts, middle-aged and older adults with schizophrenia tend to have better psychosocial functioning, including better adherence to medications and self-rated mental health, and lower prevalence of substance use and psychotic relapse. Survivor bias is not the primary explanation for this finding, and longitudinal studies show improvement in mental functioning with age. A minority of older persons with schizophrenia experience sustained remission. Reported predictors of sustained remission include psychosocial support, early initiation of treatment, better premorbid functioning, and having a spouse or partner. Two well-known examples of successful aging with schizophrenia are John Nash, a Nobel Laureate, and Elyn Saks, distinguished professor of law and psychiatry at the University of Southern California.

Connectedness Is a Social Determinant Of Health

About 25 years ago, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) increased their focus on social determinants of health. The commonly listed social factors that are discussed as having a major impact on health and longevity are mostly adversarial, such as poverty, social discrimination, unemployment, food insecurity, unstable housing, and early-life trauma. But there are positive social determinants as well, among which one of the most important is social connectedness.

In a 2010 meta-analysis published in PLOS Medicine that included 148 studies (n=308,849), many of which adjusted for confounding factors such as medications and health behaviors, individuals with greater social connectedness had a 50% increased likelihood of survival. This association became even more robust when only those studies were included that used complex assessments of social connectedness, demonstrating a 91% increased likelihood of survival.

Yet social connection has, until recently, been largely ignored as a health determinant. In May 2023, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, M.D., declared that loneliness has become a serious health crisis resulting in markedly increased deaths of despair from suicide and opioid abuse as well as physical illnesses. And last November, the WHO made loneliness a global health priority and created the Commission on Social Connection.

Interestingly, historian Fay Alberti, in her 2019 book, A Biography of Loneliness, noted that prior to the 18th century, there was no English word for what we conceive of as loneliness today—the word that existed was “oneliness,” connoting solitude. Thus, loneliness as we understand it today seems to be a product of modern social and economic conditions.

Impairment or deficit in social connectedness is associated with loneliness and social isolation. Loneliness is defined as subjective distress arising from an imbalance between desired and perceived social relationships. Social isolation refers to the limitation of the size of an individual’s social network and/or poor quality of social relationships. These two constructs are often, but not always, correlated. For example, an older adult living alone after the death of the spouse or partner is likely to feel lonely. However, such a person might be highly religious or spiritual and feel closely connected to a higher power and not feel pathologically distressed by being alone. In contrast, a college student living in a dorm with many other students and having lots of Facebook friends may feel very lonely. Loneliness is not merely a mental state but also a neurobiologically based, modestly heritable personality trait.

A 2020 report titled “Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System” from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine suggests that the effect of low social connectedness in predicting all-cause mortality rate is comparable in magnitude to that of smoking 15 cigarettes daily and greater than consuming six alcoholic drinks a day and mild to moderate obesity. Loneliness and social isolation are major risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease, major depression, generalized anxiety disorders, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, as well as alcohol and drug abuse, suicidality, poor nutrition, and sedentary lifestyle. More Americans die from loneliness-related conditions than from stroke or lung cancer. Loneliness is more common in people with serious mental illnesses than in the general population. According to the report “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community,” loneliness has led to a 33% increase in suicides and a 10-fold increase in the number of opioid-related deaths in the United States since the late 1990s.

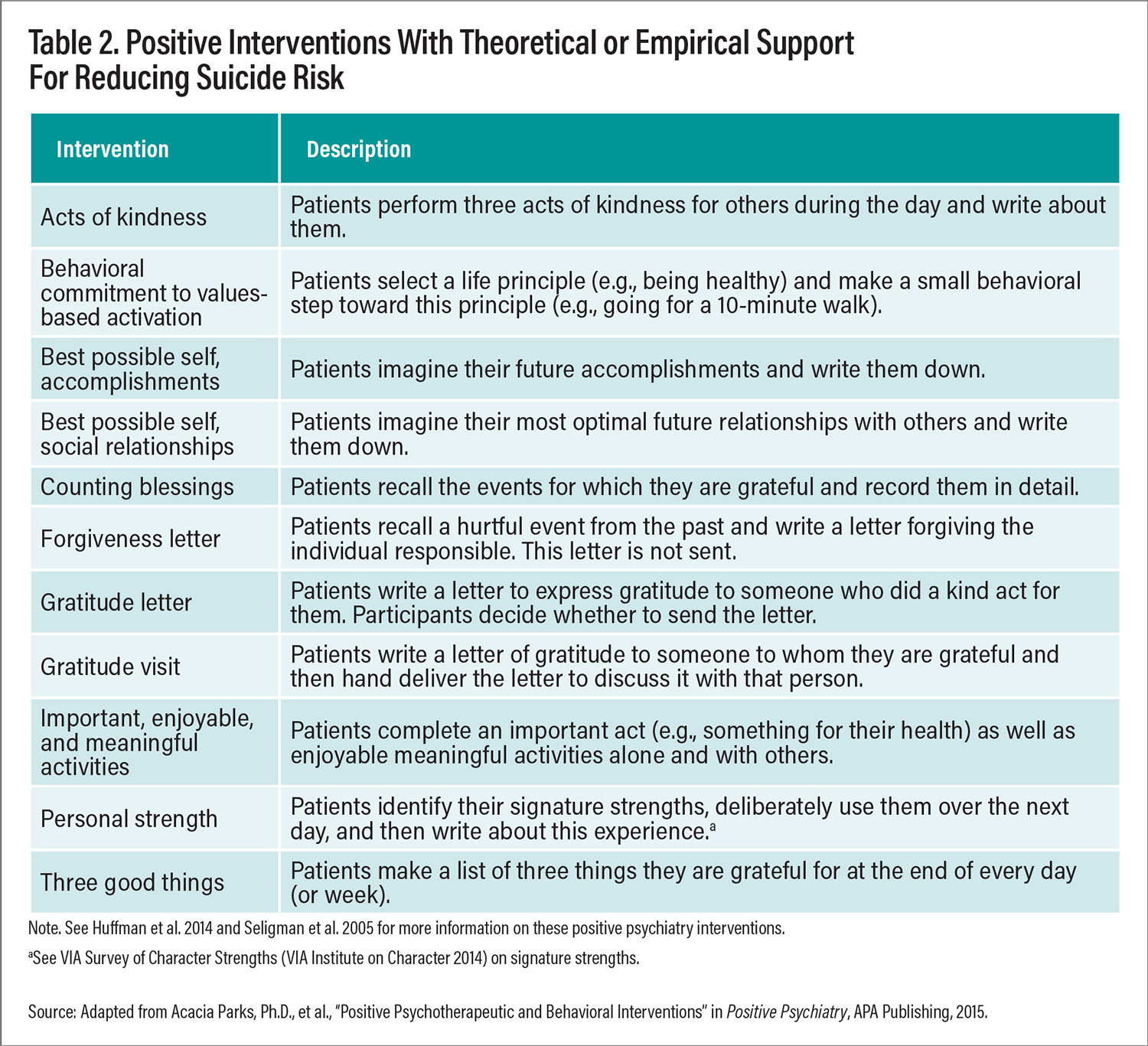

Table 2. Positive Interventions With Theoretical or Empirical Support For Reducing Suicide Risk

Furthermore, there are concerns that social connectedness may continue to erode over time due to a broad spectrum of social changes, such as the rise in the value of individualism, shift in telecommunication methods, rapid evolution of the internet, and especially (and paradoxically) the rapid growth of social media. Arguably, Facebook, Twitter (now labeled X), and Instagram have expanded global communication multifold—but just as arguably, they have markedly worsened the quality of social connections and added to individual and collective distress.

Loneliness is not merely a health problem but also a broader societal issue impacting social functioning, businesses, and governments. There is a high economic toll of loneliness from lost productivity, greater health care usage, and caregiver expenses. The COVID-19 pandemic has shaken the world since March 2020, killing millions of people. Management of COVID-19 has increased the risk for loneliness as the primary public health strategy involves social distancing.

We need a research agenda dedicated to social connectedness and loneliness (see box below). Several recent cross-sectional as well as longitudinal studies have shown a strong inverse association between loneliness and wisdom, and especially compassion and self-compassion. Moreover, the inverse association is not just clinical and behavioral but also biological, as reflected in research using EEG and gut microbiome. This inverse association suggests that interventions focusing on compassion may lead to stronger social connectedness.

Biomarkers Indicate Positive Traits

Empirical evidence supports links between measures of positive psychiatry and biomarkers for epigenetics, allostatic load, inflammation, and microbiome, although the literature on the impact of these factors in people with serious mental illnesses has been sparse.

A Research, Policy, and Clinical Agenda for Social Connection

In late 2022, my colleagues and I published “Social Disconnection as a Global Behavioral Epidemic—A Call to Action About a Major Health Risk Factor” in JAMA Psychiatry. Below is a summary of what we believe is essential.

Promote health policy initiatives to facilitate positive social connections: Emerging health policy efforts in different nations have supported interventions to promote social connections at a community level. For example, in the United Kingdom, a core pillar of health care involves “social prescribing” as a means of improving the health of patients who present to their primary care physicians. In this setting, general physicians refer patients to “link workers” who are trained to provide nonmedical services such as support and advice on physical activity, loneliness, social networking, job hunting, housing, and financial hardship. In the United States, the Veterans Health Administration offers a tele-support program called the Compassionate Contact Corps, where clinicians link veterans with a volunteer worker via phone or video calls to bolster social connections.

Educate the public and medical community about the importance of social connections: It would be useful to educate patients and their families about the importance of social and emotional skills beginning in grade school, as well as health professionals in medical/nursing school, residency, and postgraduate education. Such curricula should include assessment and intervention strategies, which seek to enhance positive social connections and thereby promote better health outcomes and reduced mortality risk.

Develop and validate measures to assess and monitor social connections in health care settings: Addressing social disconnection should start with early detection while gathering patient histories in daily practice. Paralleling the practice of primary care–based implementation of brief screening measures to assess problematic alcohol use, health care providers should administer validated but pragmatic scales to assess and monitor levels of social connectedness. Currently, there are no brief standardized measures in the electronic health records that capture the range of social connections. Thus, efforts to develop and validate brief and repeatable versions of commonly used standardized measures of social connectedness such as the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale are needed to improve early detection and monitoring of social disconnection.

Evaluate clinical interventions to enhance positive social connections: For example, peer-outreach interventions have been reported to improve social connectedness and depressive symptoms in different populations and settings. Adequate evaluation of the efficacy and effectiveness of these and other interventions that seek to enhance positive social connections warrants the same level of rigorous methodology that is expected in clinical trials of medications and psychotherapies.

Genomics and epigenetics

Genes linked with resilience have varied functions, from HPA-axis activity to neurotransmitter involvement. Serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms have been shown to interact with childhood adversity, affecting the development of anxiety and affective disorders. Genes related to the stress axis may influence cognitive and emotional empathy and, thereby, vulnerability to the psychopathology associated with childhood adversities. Several studies also suggest that the vasopressin receptor genes are associated with pro-social behavior and emotional empathy.

Allostatic load

Allostatic load—the cumulative toll on the body as it adapts to environmental stressors—has important implications for physical diseases. For example, a sustained stress response can precipitate a series of changes that reduce neuroplasticity, resulting in worse cognitive functioning. Indices of allostatic load include systolic and diastolic blood pressure, body mass index, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and cortisol. Studies have shown that social support, optimism, hope, and personal mastery are associated with decreased allostatic load. Conversely, psychosocial stressors such as childhood abuse and neglect as well as poor social connections are associated with increased allostatic load.

Inflammation and immune function

Children and adults with higher perceived self-efficacy, optimism, empathy, spirituality, and engagement in pleasant activities have less systemic inflammation (for example, lower levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein). Similarly, high levels of personal mastery may be protective against the inflammatory consequences of chronic stress and exposure to trauma.

Microbiome

Growing evidence supports the functionality of a gut-brain axis with bidirectional communication between gut microbiota and brain through a network of chemical transmitters, neural connections, and immune signals. In a 2021 article in Frontiers in Psychiatry, we reported that greater diversity of gut microbiome is associated not only with better physical health but also with higher levels of social engagement, compassion, and wisdom, in contrast to loneliness, which is associated with worse physical health and less diversity of the gut microbiome.

Biology of loneliness

Neurobiological data suggest that when individuals experience social rejection, there is increased activation of their stress response system, as well as brain regions activated by physical pain, such as anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortex. Studies using EEG, structural and functional brain imaging, neurochemistry, neuropathology, and genomics have reported overlapping neurobiological correlates of loneliness and compassion, often in opposite directions. Several brain regions are implicated, including prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices, the insula, amygdala, and reward circuitry.

Interventions Can Target Positive

Psychological and Social Factors

As discussed above, positive factors have implications for mental, cognitive, and physical health. Positive psychiatry interventions (PPIs) are a broad category of treatments that differ from traditional behavioral interventions in that they focus not on reduction in psychiatric symptoms, but on enhancement of well-being and happiness. Overall, the published studies have reported small- to medium-sized effects of PPIs on well-being in adults including older adults. The following is a summary of major categories of these interventions.

Resilience intervention studies

Studies using valid measures of resilience have reported positive outcomes with small to medium effect sizes. A group-based intervention aimed at increasing positive emotions demonstrated a significant increase in resilience. Another six-session group resilience intervention for older adults with chronic illnesses (heart conditions, diabetes, and arthritis) involving shared lived experiences, relaxation techniques, management of stress, and coping strategies produced a significant increase in perceived resilience.

Wisdom interventions

A meta-analysis of interventions that targeted specific components of wisdom identified 57 randomized, controlled trials: 29 focused on prosocial behaviors, 13 on emotional regulation, and 15 on spirituality. There was considerable heterogeneity of populations targeted, scales used, and intervention characteristics. The results showed that 47% of the trials had positive impact with medium to large effect sizes. For example, participants in a high-intensity, eight-session, group-based self-compassion intervention and another self-help intervention with self-compassion lessons and email guidance demonstrated improved self-compassion and well-being compared with the control group. Five spirituality interventions also demonstrated significant improvements in spirituality.

Meaning in life interventions

Interventions aiming to enhance meaning in life among patients with advanced diseases, with two to eight sessions of 30 to 90 minutes each, found a medium to large effect size for pooled positive outcomes of meaning of life, spiritual well-being, quality of life, anxiety, and physical symptoms. Life review interventions, which are individual or group storytelling interventions with a focus on integrating life stories through different phases in life, had a medium to large effect size on subjective well-being and depressive symptoms in older adults, including some with dementia.

Mind-body interventions

Mindfulness interventions have been reported to improve the body’s physiological response to stress by promoting acceptance and nonreactivity toward potential stressors, thus facilitating constructive reframing. Brain imaging studies suggest that mindfulness enhances neurocircuitry associated with increased empathy and emotional processing. While there has been a concern about the possibility of meditation leading to symptom exacerbation (and even an acute psychotic episode) in people with schizophrenia, a recent meta-analysis of 13 studies showed moderate positive effects of mindfulness interventions on negative symptoms in schizophrenia.

Similar to mindfulness, yoga-based treatments have been reported to have a positive impact on self-regulation and psychological resilience. A 2013 systematic review and meta-analysis published in BMC Psychiatry on the impact of yoga on clinical outcomes in people with schizophrenia found moderate effect sizes for quality of life, but yoga interventions did not outperform an exercise treatment. Another systematic review of yoga therapy as an adjunct to conventional psychological treatments reported lower psychotic symptomatology and improved quality of life compared with exercise interventions and to wait-list.

A therapeutic approach that is related to but distinct from mindfulness and yoga is focused compassion training. Self-compassion meditation training has been reported to reduce anxiety and improve physiological responses to social stressors. Compassion mediation has been shown to decrease social stress-induced inflammation. Increased spirituality is also associated with improved depressive symptoms; decreased risk for mental illness; and increased purpose in life, gratitude, and posttraumatic growth.

Recent research suggests an important role for psychotherapies to promote the well-being and overall health of individuals with psychiatric disorders through a focus on social determinants of mental health. For instance, a 2021 report in Molecular Psychiatry found epigenetic changes with trauma-focused psychotherapy that can potentially reverse the adverse genomic effects of early-life trauma.

Positive psychiatry has the potential to revolutionize the assessment and treatment of people suffering from mental illnesses. There already exists a wide array of psychometrically sound instruments to measure the core facets of positive psychiatry. Researchers have assessed resilience, wisdom, meaning in life, optimism, religiosity, spirituality, and social connectedness, and this literature suggests that these positive factors serve as protective factors against the negative effects of illness on health and well-being. We look forward to the continued development of positive psychiatry and its integration into the field of psychiatry and even medicine as a whole. ■

References

Approaching Whole Health: New Approach for Veterans and the Nation

Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-Analytic Review

Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System

Association of Loneliness and Wisdom With Gut Microbial Diversity and Composition

Yoga for Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis