Special Report: Psychiatrists Critical in Screening, Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder

Abstract

Despite the wide prevalence of alcohol misuse and the existence of evidence-based treatments, including three FDA-approved medications, only a small percentage of people with alcohol use disorder receive treatment.

Alcohol remains the most commonly used and misused substance in the United States. In 2021, there were nearly 174.3 million people aged 12 and up who reported past-year alcohol consumption, 2 million emergency department visits related primarily to alcohol, and over 140,000 alcohol-related deaths, according to the U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). This makes excessive alcohol consumption the fourth-leading preventable cause of death in the United States.

Alcohol use has significant consequences—among them are impairment across major areas of functioning; disrupted academic/work performance; interference with interpersonal relationships; and increased risk of violence, suicide, and overall accidents, including motor vehicle accidents.

Alcohol-related medical complications are significant and include alcohol-associated liver disease, which can involve steatosis (fatty liver), steatohepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and alcohol-associated hepatitis. Alcohol-associated liver disease is responsible for 80% of liver-disease deaths and is the most common indication for liver transplantation.

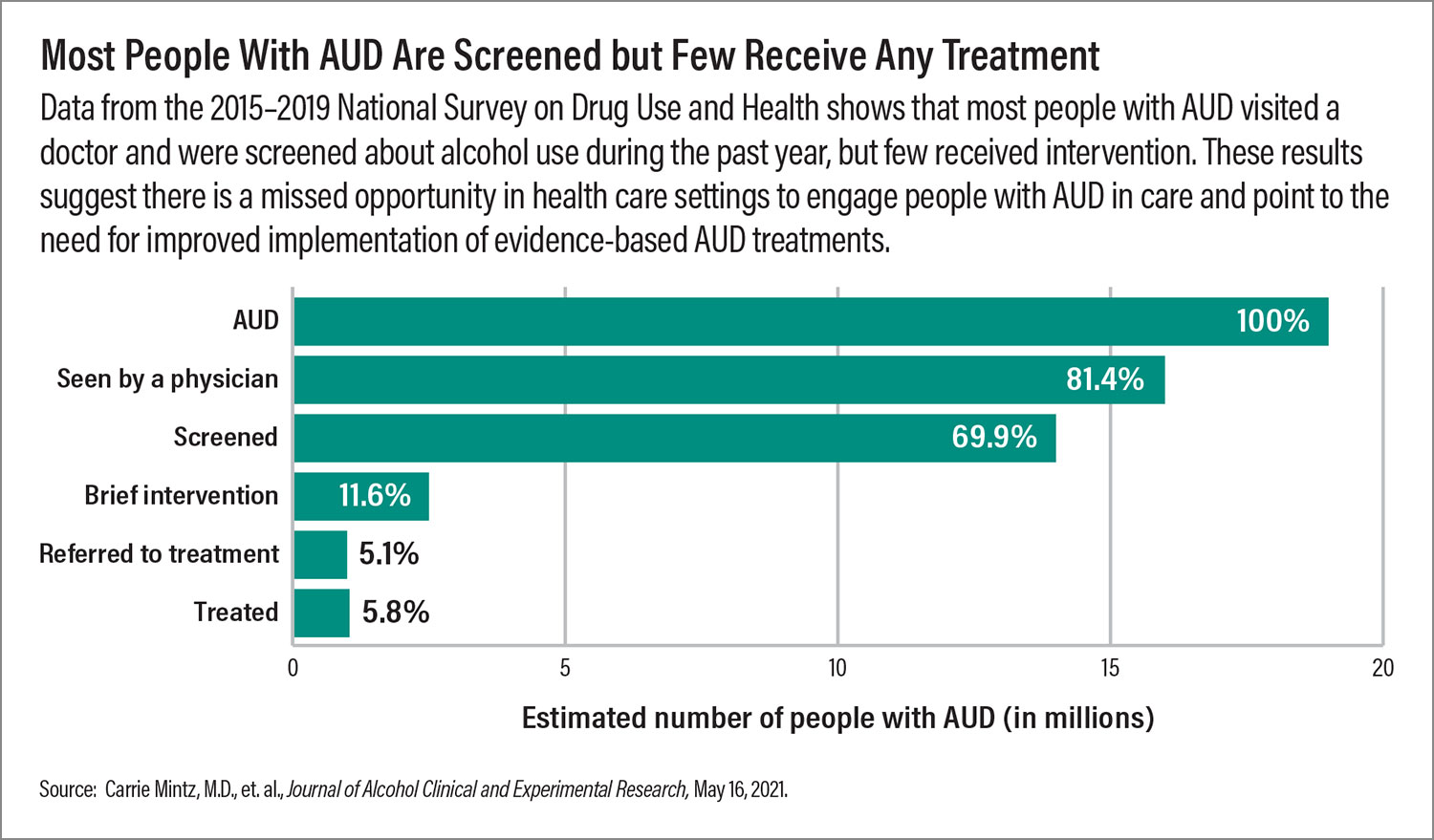

Most People With AUD Are Screened but Few Receive Any Treatment

Alcohol affects the entire body, not just the liver, including the brain, gastrointestinal tract, cardiovascular system, and immune system. Alcohol is a carcinogen associated with multiple forms of cancer. Chronic heavy alcohol consumption is the leading cause of chronic pancreatitis and can lead to nutritional deficits and subsequent neurological syndromes, such as the Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome.

Alcohol interacts with many medications, including those commonly prescribed by psychiatrists. Patients with depression who are taking antidepressant medications may have reduced treatment response and adherence, even with low levels of drinking. Sedative and anxiolytic medications can have synergistic effects with alcohol, increasing the risk of accidental overdose. Alcohol has also been found to contribute to over 20% of opioid overdose deaths.

In addition to the individual-level impacts, hazardous drinking has significant effects on families, communities, and the population at large. According to the U.S. surgeon general, the annual economic impact of alcohol misuse costs the United States economy $249 billion annually.

Spectrum of Drinking: From Alcohol Use to Alcohol Use Disorder

Prevalence

According to the 2021 NSDUH, nearly 30 million Americans met past-year DSM-5 criteria for alcohol use disorder (AUD). Lifetime prevalence of AUD was estimated to be 29% (8.6% mild, 6.6% moderate, and 13.9% severe). In addition, there were significant racial/ethnic differences in heavy alcohol use among Americans 12 years and older, with White Americans having the highest rate (6.7%) and Asian Americans having the lowest rate (1.9%).

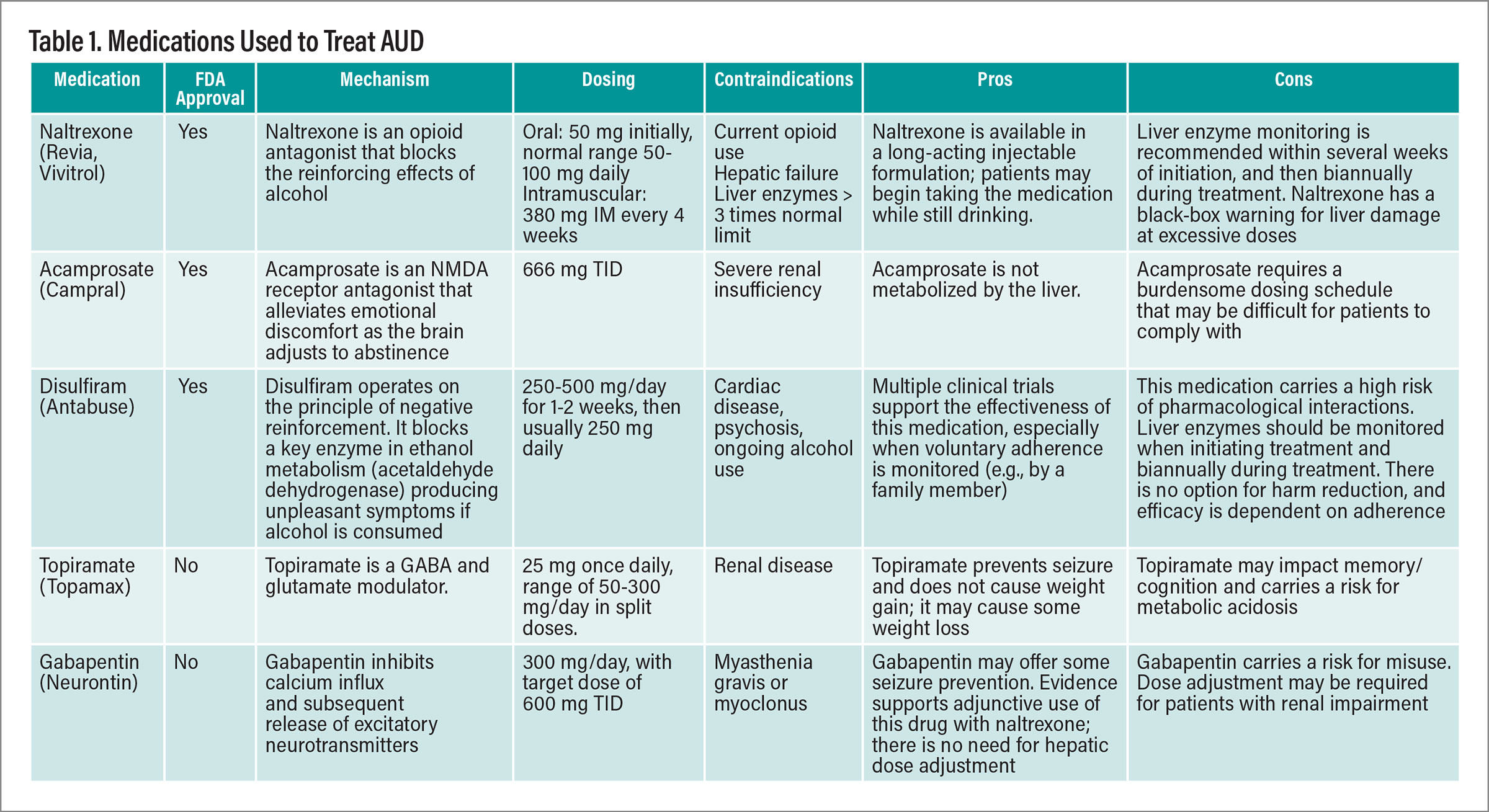

Table 1. Medications Used to Treat AUD

Various risk factors for developing AUD have been identified, including environmental risk factors such as poverty, discrimination, structural inequalities, cultural attitudes, and stress levels. There is also a significant genetic risk, as those who have a close relative with AUD have a three to four times higher risk of developing AUD themselves. Patients who have specific psychiatric diagnoses, particularly schizophrenia or bipolar spectrum disorders, are also at an increased risk.

Neurobiology

Acute and chronic alcohol use impacts multiple neurotransmitters, including serotonin, dopamine, gamma-aminobutyric acid, glutamine, acetylcholine, and the endogenous opioid systems. This disruption can affect normal brain activity and lead to dysregulation in the natural reward system.

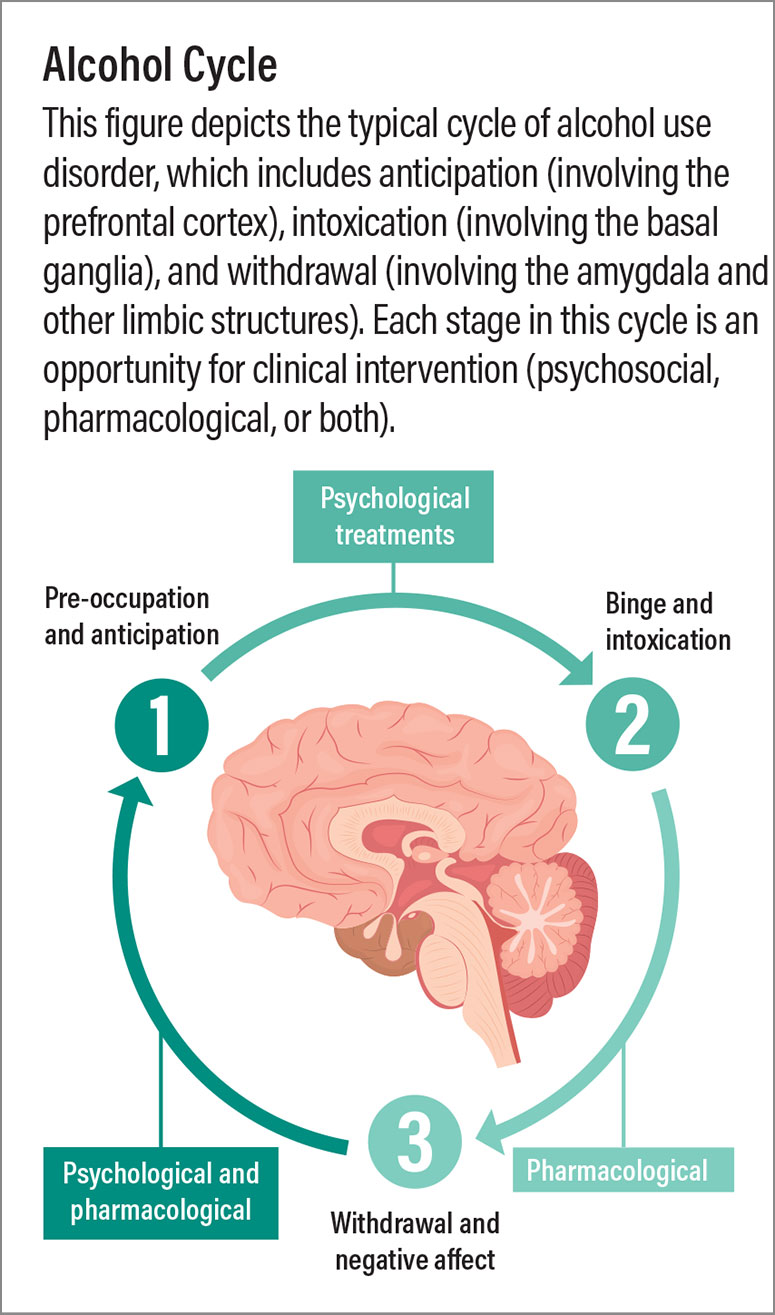

Addiction to alcohol occurs in three phases involving different brain regions. First is the “preoccupation and anticipation stage” involving the prefrontal cortex. Second is the “binge and intoxication stage,” primarily involving the basal ganglia. And third is the “withdrawal and negative affect stage,” linked to changes in the amygdala and other limbic structures. At each stage, clinicians can effectively intervene (see figure below).

Alcohol use versus alcohol use disorder

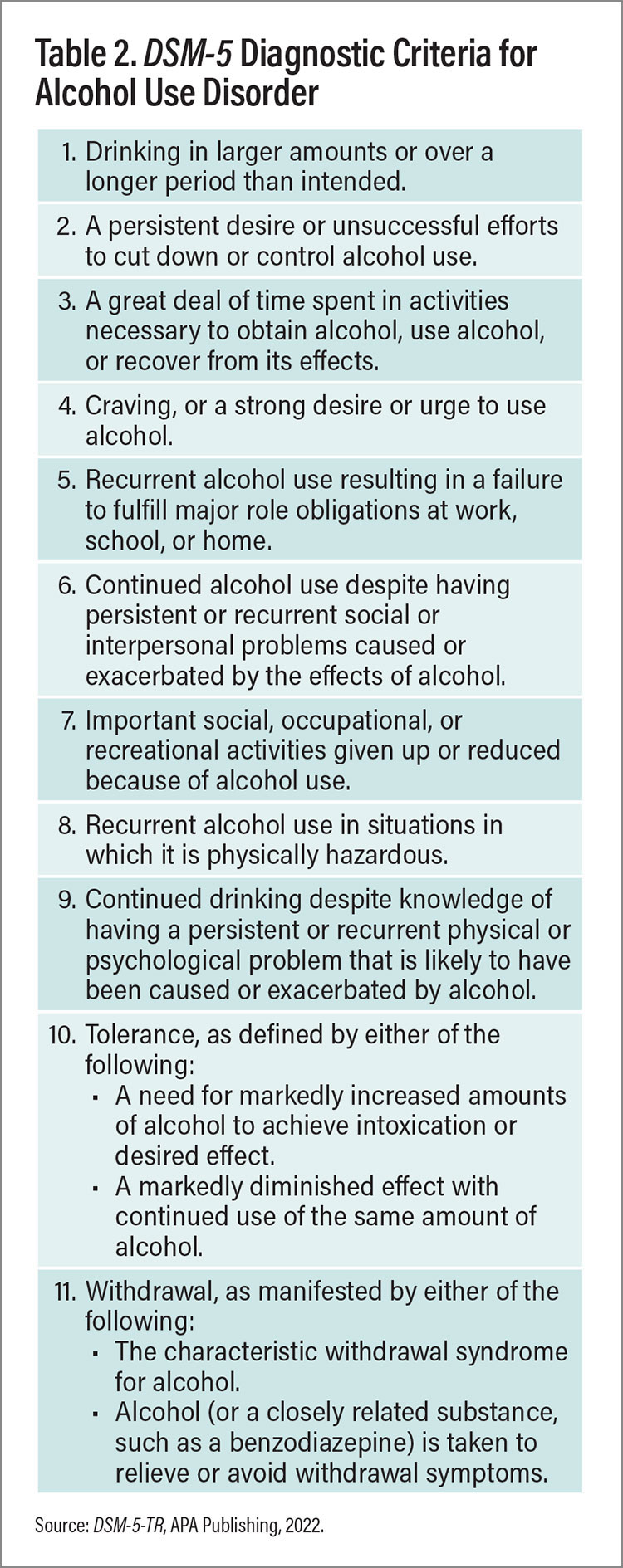

The majority of people who use alcohol do not meet the criteria for AUD. In contrast to alcohol use, AUD is characterized by an inability to control alcohol consumption despite negative health, social, and/or occupational consequences. The criteria for diagnosing AUD have changed somewhat over the years, with DSM-5 moving AUD from a binary diagnosis (alcohol abuse versus alcohol dependence) to a spectrum of illness, with the severity of AUD now defined by the number of individual symptoms that someone experiences. Notably, in DSM-5 craving for alcohol was added as a criterion, while having legal problems was removed. Also removed was the requirement to experience withdrawal symptoms when consumption stops, which is particularly notable because many people with AUD are not physiologically dependent on alcohol.

Alcohol Cycle

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic

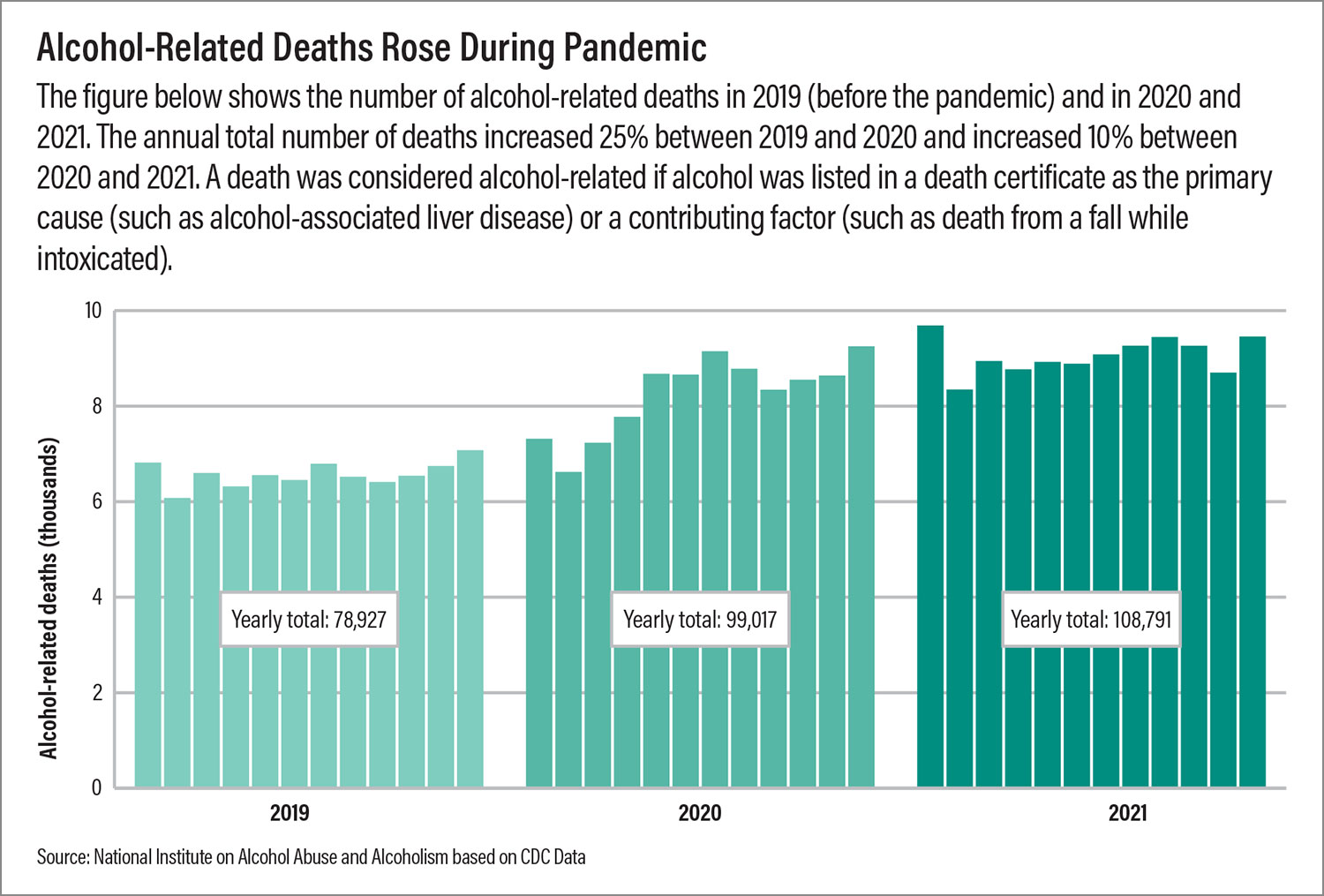

In the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, alcohol sales increased by almost 3%. Twenty-five percent of people reported drinking more than usual, and deaths related to alcohol-linked liver disease increased by over 22%. One meta-analysis sought to identify predictors of increased alcohol use and found that the mean change in alcohol consumption was nonsignificant. However, 23% of individuals significantly increased their consumption, which has been interpreted to mean that there was an increase in heavy alcohol consumption among some individuals, while people who typically drank only socially may have consumed less. Predictors of increased drinking included contextual changes (such as income loss, remote work and resulting isolation and anxiety, children at home) as well as factors related to mental illness (such as worsening depression or anxiety).

AUD Prevention and Screening

Despite the high prevalence of AUD in this country, many patients go undiagnosed, and even fewer receive any treatment: less than 10% receive any treatment, and less than 2% receive one of the three FDA-approved medications—naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram. The APA Practice Guideline on the Pharmacological Treatment of Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder recommends that all patients with suspected AUD be assessed for use of all substances.

Intervening early in the course of AUD can lead to better outcomes. For example, individuals who engage in heavy drinking are at increased risk of developing AUD. According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, “heavy drinking” is defined as four or more drinks in one day (or eight or more a week) for women, and five or more drinks in one day (or 15 or more a week) in men. Additional research is needed to create a definition that is inclusive of nonbinary and other gender-diverse populations.

Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) is an evidence-based paradigm for prevention and early detection of AUD. In the SBIRT model, all patients complete a validated screening instrument (for example, the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test for adults or the CRAFFT for adolescents; CRAFFT stands for Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble). Those who meet DSM-5 criteria for AUD are referred for full evaluation and formal evidence-based AUD treatment.

General Psychiatrists Can and Should Treat AUD: A Case Study

Ms. A, a 28-year-old woman with no formal medical or psychiatric history, presents to your outpatient psychiatric practice for “anxiety and insomnia.” She reports several years of sleep-initiation insomnia, as well as intermittent feelings of anxiety. A few months ago, her primary care physician prescribed escitalopram 10 mg daily for symptoms of anxiety, which Ms. A did not find helpful and subsequently discontinued. This prompted a referral to your office. While initially hesitant, Ms. A was convinced to attend the appointment by her partner, who felt that Ms. A “needed help” because of increasing irritability and seeming to be more “on edge.” On further interview, Ms. A discloses consuming three to four glasses of wine each night after returning home from her job as an accountant and five to six drinks on Saturdays.

Given this history, you administer the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) to screen for alcohol use disorder (AUD). Ms. A receives a score of 21, indicating a high likelihood of moderate to severe AUD. On discussing these findings with Ms. A, she discloses significantly increased alcohol consumption over the past several years. She has tried to cut back on drinking because of arguments with her partner when she is intoxicated and because she hates feeling “hungover” at work. However, cutting back has been extremely difficult.

You are initially hesitant to treat Ms. A because your outpatient practice is not primarily focused on substance use disorders. However, you know there is a shortage of specialist addiction psychiatrists. Additionally, APA advocates for general psychiatrists to treat patients with co-occurring substance use disorders and provides resources like the APA Practice Guideline for the Pharmacological Treatment of Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder. (The guideline is expected to be updated this year.)

When discussing treatment goals with Ms. A, she reports being highly motivated to decrease her alcohol consumption but is not interested in complete abstinence. She sets an initial goal to decrease her daily alcohol consumption from three to four glasses to one to two glasses. After discussing risks and benefits of the FDA-approved medications for AUD and obtaining routine baseline laboratory tests, Ms. A provides informed consent to start naltrexone 50 mg daily. She also accepts a referral for weekly cognitive-behavioral therapy to help her identify triggers for drinking and alternate coping strategies for stress and anxiety. She declines information about Alcoholics Anonymous, citing her personal religious beliefs and nonabstinence treatment goals. However, she accepts a brochure about Smart Recovery (a non-faith-based, mutual self-help program for AUD).

Over the course of the next year in treatment, Ms. A significantly decreases her alcohol consumption. She also reports improvements in sleep quality, anxiety, mood, and energy. For convenience, she elects to transition from oral naltrexone to monthly intramuscular depot naltrexone and continues to benefit from weekly therapy and occasional Smart Recovery meetings.

AUD remains a clinical diagnosis, with no definitive diagnostic instrument or laboratory test. However, in addition to the screening tools mentioned above, there are assessments such as the 11-item Alcohol Symptom Checklist, adapted from the diagnostic criteria in DSM-5, which can help make the diagnosis as well as establish the severity of AUD.

Laboratory tests can be helpful in detecting heavy alcohol use and monitoring treatment response. Alcohol biomarkers include gamma-glutamyltransferase, carbohydrate-deficient transferrin, and ethylglucuronide. Other indirect biomarkers (such as liver function tests, mean corpuscular volume, uric acid, and lipid profile) can help measure the impact of alcohol on the body. Presenting patients with such objective evidence of bodily harm can sometimes overcome ambivalence about starting AUD treatment. For more information on alcohol biomarkers, including their relative strengths and limitations, see the APA Practice Guideline on the Pharmacological Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder.

Treatment Goals and Treatment

Collaboratively establishing treatment goals with patients should include a personalized discussion of the alcohol-related harms they are experiencing (for example, relationship and job problems, medical problems, psychological impact) and the risks of continued alcohol use. Historically, abstinence was viewed as the only effective way to recover from AUD and was the primary endpoint of much AUD treatment research. However, for many patients, researchers and clinicians have found that moderation goals (reducing heavy alcohol consumption or reducing drinking in high-risk situations) can improve health outcomes and mitigate the impact of AUD. While abstinence may remain the safest course for specific subgroups of patients, nonabstinence-based treatment that embraces a harm-reduction philosophy allows clinicians to reach a wider segment of the population with AUD.

Alcohol-Related Deaths Rose During Pandemic

For individuals who screen positive for potential AUD, clinicians deliver a 5- to 10-minute brief intervention based on principles of motivational interviewing. The goal is to help patients identify ways that alcohol may be negatively impacting their lives and to collaboratively set short-term goals to reduce alcohol-related harms.

Most AUD treatment occurs in the outpatient setting and involves regular office visits. The preferred approach to treating patients with AUD outside of the acute intoxication and withdrawal stages is a combination of pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions. Continued care across settings (inpatient and outpatient) is recommended to achieve long-term recovery.

Evidence-based AUD psychotherapies include cognitive-behavioral therapy to identify and manage cues that lead to heavy drinking, motivational enhancement therapy to overcome ambivalence about reducing or stopping drinking, and 12-step facilitation to help patients make optimal use of mutual self-help groups like Alcoholics Anonymous. Community-based mutual self-help groups (Alcoholics Anonymous, Smart Recovery, Moderation Management) may also be helpful for patients, particularly because they reduce social isolation and provide interaction with others in recovery.

Commonly used pharmacological interventions are described in the table on the facing page. Pharmacotherapies are significantly underutilized; in 2022, only 2.1% of adults with AUD received medication treatment, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Physicians may not be familiar with the FDA-approved medication treatments for AUD or they may feel inadequately trained about AUD. Additionally, some providers and patients may have misconceptions about medication treatments for AUD, despite the robust evidence base for their efficacy.

Table 2. DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Alcohol Use Disorder

In addition to treating patients for AUD, it is important to assess and manage alcohol withdrawal in patients who drink alcohol on a regular basis. The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment (CIWA) is a commonly used method for assessing and quantifying alcohol withdrawal symptoms. Mild symptoms can include insomnia, gastrointestinal upset, headache, and diaphoresis. More severe withdrawal can involve electrolyte abnormalities, seizures, hallucinosis, and cognitive impairment (delirium tremens). Often, mild withdrawal symptoms can be managed in the outpatient setting. Patients who have severe withdrawal symptoms or are medically compromised may require inpatient, medically managed treatment.

Benzodiazepines remain the standard of care for treating acute alcohol withdrawal. The most frequently used benzodiazepines are diazepam (Valium), lorazepam (Ativan), and chlordiazepoxide (Librium). A symptom-triggered approach (rather than a standing taper), using standardized measures such as the CIWA is preferable.

Implications for Psychiatric Practice

AUD often co-occurs with other mental disorders, including depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, trauma-related disorders, sleep disorders, and other substance use disorders. As previously mentioned, individuals with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and ADHD are at elevated risk for developing a substance use disorder. In fact, pre-existing psychiatric disorders more broadly can increase the risk of developing AUD, likely due in part to people using alcohol to cope with psychiatric symptoms. Heavy and hazardous drinking may also be a consequence of impulsivity in individuals with schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, ADHD, or borderline personality disorder. Therefore, it is important to screen all patients for the presence of AUD and other substance use disorders. The likelihood of recovery from AUD and a co-occurring psychiatric condition is highest when patients are treated for both simultaneously.

Despite the high morbidity and mortality associated with AUD, recovery is possible with access to evidence-based psychotherapy and medication treatments. Unfortunately, there are fewer than 2,000 physicians nationwide certified in addiction medicine, and fewer than 1,300 physicians certified in addiction psychiatry. Therefore, primary care providers and general psychiatrists are critical to addressing the public health burden of AUD. APA and its partner organizations offer multiple opportunities for education and training on evidence-based AUD treatment. Together, we can meet the needs of our patients with AUD and other substance use disorders to have a truly meaningful impact on their health and well-being. ■