Special Report: Thriving in Residency Training: Establishing Identity, Finding a Mentor, and Growing as a Clinician

Abstract

July 1 is right around the corner. Are you a new psychiatry resident or entering another year of training? Here is a “road map” that may help you focus your energies as you progress through your residency while also keeping the big picture in mind.

“You are embarking on a comprehensive training to equip you to help your patients live healthier and more fulfilling lives. Your training will include seemingly disparate areas of focus from neuroscience, psychotherapy, quality improvement, and teaching to navigating cultural differences and social advocacy, yet all are core aspects of the psychiatric experience. While striving to integrate an intensive training experience, you will be navigating a formative period in your personal life, bridging possibly your last “training” experience and your first unsupervised job as a psychiatrist. Our hope is to help make your journey as smooth and meaningful as possible by making explicit that which is often left implicit during training, leading to confusion, frustration, and/or missed opportunities.”

—DeGolia and Wang, The Psychiatry Resident Handbook: How to Thrive in Training

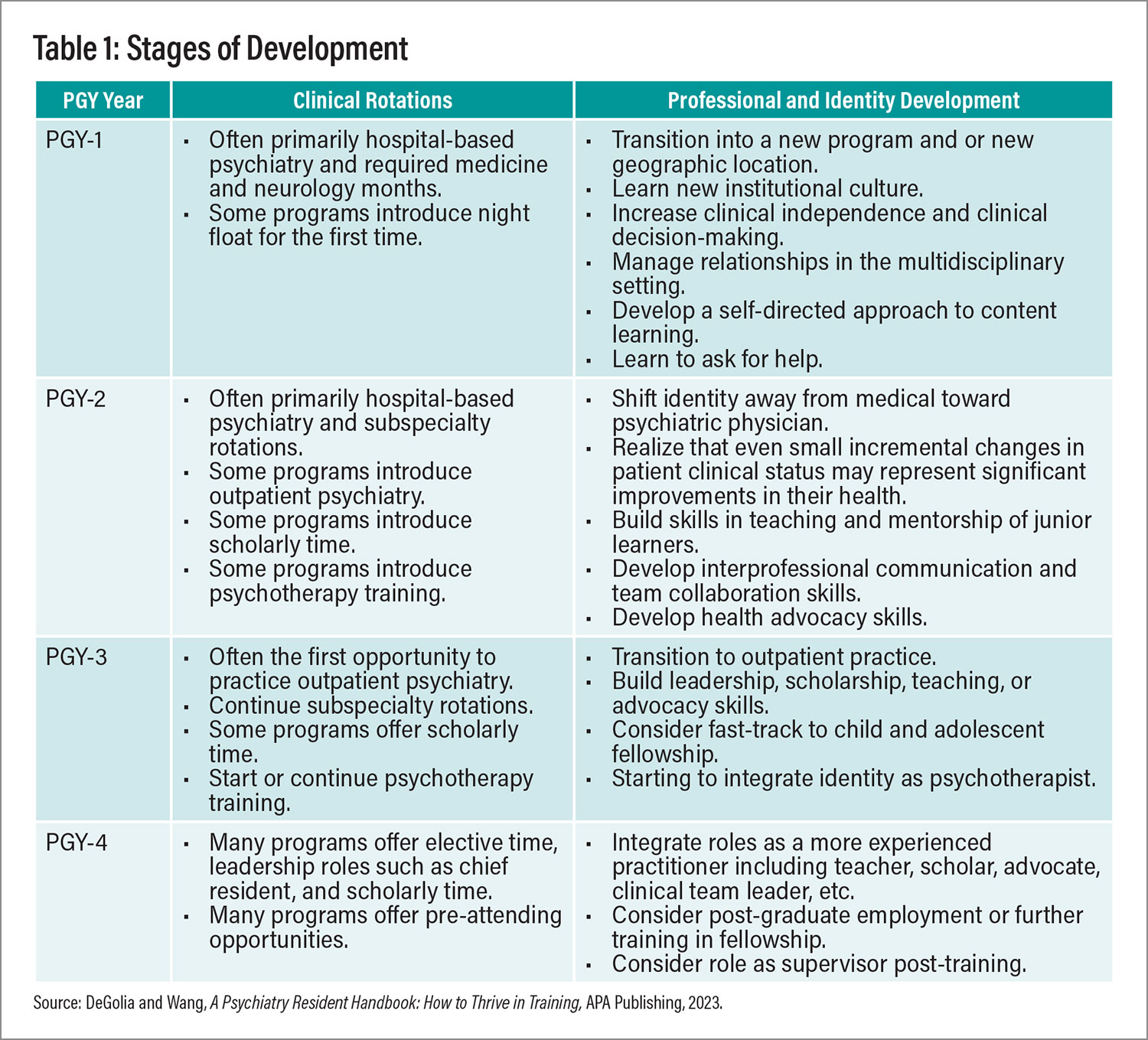

Even if you aren’t new to psychiatry residency training, there are many challenges you will face that are not always transparent or anticipated. Multiple factors will impact your experience (see Table 1), but keeping an eye on meaning, finding the appropriate support and mentorship, and being able to anticipate roadblocks may help. Table 1 describes the stages of development through psychiatric training and the professional and identity development tasks you will no doubt face.

Finding Belonging and Support

A key early milestone in psychiatry training is developing your identity as a psychiatrist and a sense of belonging to your training program as well as the field. This process, however, can seem to be in tension with your identity as an individual person with a variety of attributes, experiences, and perspectives distinct from your colleagues’. But as Matthew Edwards, M.D., and Michael Polignano, M.D., suggest (perhaps counterintuitively) in the chapter titled “Centering Our Identities” in our APA Publishing textbook, The Psychiatry Resident Handbook: How to Thrive in Training, these personal “differences are strengths that are key to being a good psychiatrist.” After all, our patients seek care from a broad spectrum of experience, identity, and need, and our own differences may help us have empathy for their journeys. Finding community in your training program, in spite of differences, can allow you, in turn, to provide this type of holistic and compassionate care.

Finding community, however, can be easier said than done, especially for residents who are underrepresented in medicine, LGBTQ+ residents, and international medical graduates (IMGs), among others, who face structural and systemic discrimination. It behooves programs and program leaders to recognize and dismantle these structures, while promoting equity through community building, mentorship, and social supports. If this is missing from your program, finding mentors within or outside your department can be one avenue toward building your own community network.

Finding a Mentor

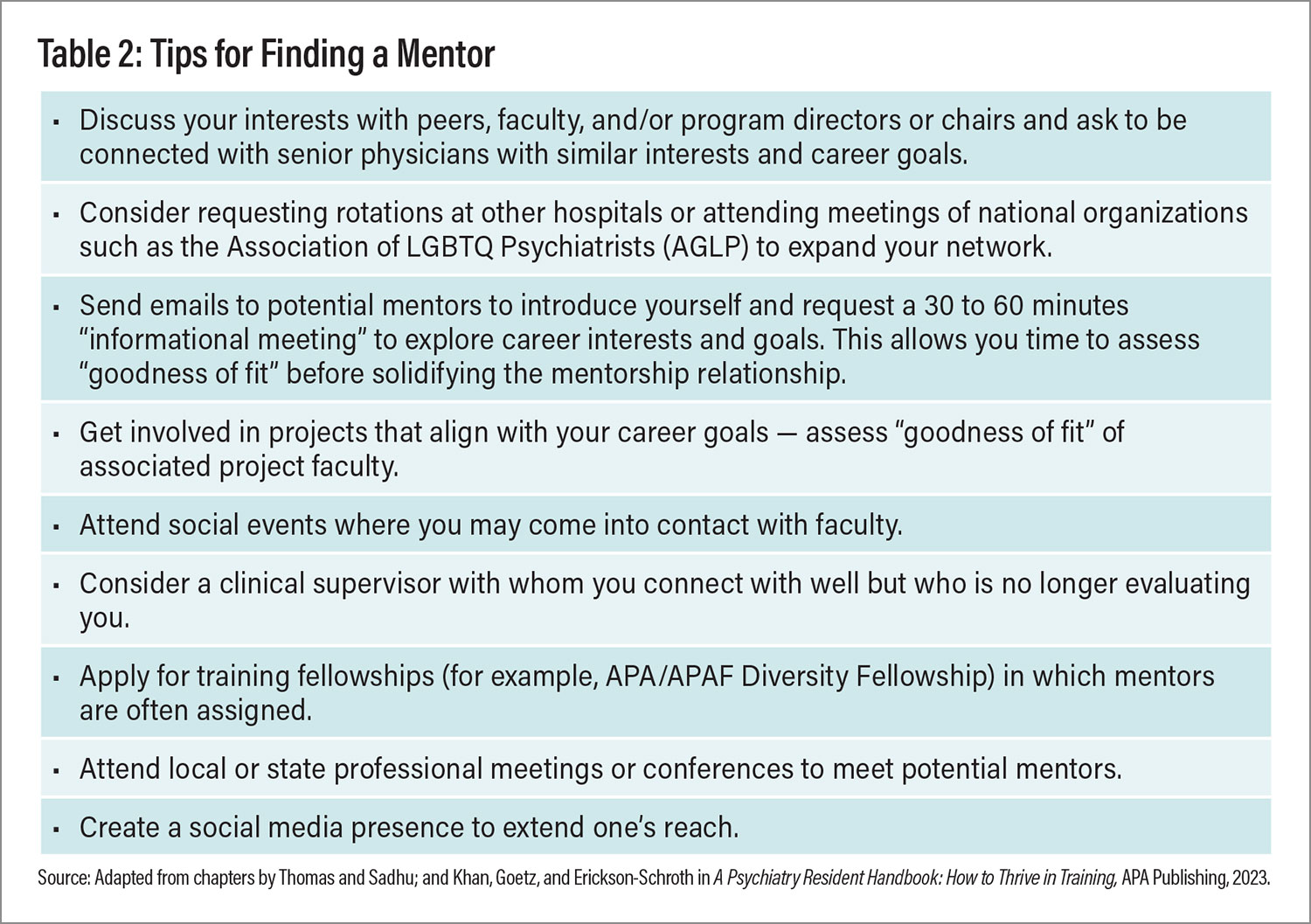

Mentorship can help you integrate within your program, manage the multitude of issues that arise during training, and develop a career trajectory. Mentorship is a relationship—finding the right “fit” is critical. Your ideal mentor may be different from a peer’s ideal mentor. An “ideal” mentor usually is described as someone who is altruistic, honest, open, trustworthy, and an active listener who is nonjudgmental, accessible, and sincere. Although having aspects of your personal identity in common with a mentor can be helpful, seeking out mentors from different backgrounds may lead to a rich experience. In cross-cultural mentoring, both parties acknowledge the personal attributes brought to the relationship by the other and makes them part of the mentoring experience.

That being said, sometimes it’s essential to have a mentor who shares a personal identity attribute that is important to you. If appropriate mentors are not available in your program, consider accessing other resources at your institution that might support residents who are underrepresented in medicine, LGBTQ+, international medical graduates, and so on. In the Handbook chapter titled “The Underrepresented in Medicine Experience,” Daniella Palermo, M.D., and Tracey M. Guthrie, M.D., suggest that requesting rotations in other residency programs or locations or even attending meetings of national organizations might also offer more mentorship options.

Once potential mentors are identified, consider setting up a brief meeting to get to know them. What are their interests? How did they get there? If the “fit” feels compatible with someone, ask the individual to consider serving as your mentor. At this point, you need to develop your mentoring goals, negotiate frequency of meetings, and determine expectations within the mentoring relationship.

Because of their limited time availability, not all faculty will be able to accept this request. Do not get discouraged. Informal mentoring is another option that is less structured with fewer expectations over a shorter period of time. This can include one-time guidance on a project or career path. Finding mentors outside one’s program can also be helpful.

Always be aware of two common mentorship pitfalls: (1) choosing a mentor primarily on the basis of the individual’s prominence in the department or field rather than other qualities that might lead to a good fit; and (2) rushing to solidify a mentoring relationship after just a few meetings. The process of assessing the right fit for your career goals and personality requires time, patience, and diligence.

Moving Toward Clinical Mastery

Even with a great mentor, psychiatry training is difficult. Especially in the first year, you might sometimes feel as though you’re experiencing whiplash as you transition between services on medicine, neurology, inpatient psychiatry, psychiatric emergency room, consult-liaison psychiatry, and outpatient work. Each rotation requires new skills, knowledge, and integration into a brand-new multidisciplinary team. Early in training and often while on call or night float, you may be asked to manage high-acuity and high-volume clinical situations with (ironically) the highest levels of independent practice. This can be understandably overwhelming! And you simply cannot know everything, nor are you expected to. Ultimately, however, there are some core skills in clinical care that are transferable across almost all psychiatric clinical work to ensure safety, build trust and rapport, establish boundaries, and develop a case formulation.

Optimizing Safety

Awareness of your setting, which includes not only your surroundings but also your behavior and body language and those of your patients, is of key importance in maintaining safety. Creating an environment of safety to prevent injury and foster trust—the foundation of psychiatric clinical care—is especially relevant in acute care settings but also in outpatient and other settings. So how do you maintain safety?

As Juan Lopez, M.D., and Clay Barnes, M.D., described in their Handbook chapter titled “The Psychiatric Emergency,” the physical layout of your unit and your clinical care setting is important. Interacting with the patient in a layout that allows either of you to exit the conversation at will may decrease the patient’s anxiety as well as any risk of injury. Particularly when interacting with seriously mentally ill patients, maintaining an appropriate distance with a neutral body stance with hands visible in a relaxed position and keeping eye contact intermittent and less intense can be helpful. It’s important within the layout of your setting to know how to get assistance if your patient becomes agitated and aggressive. Where do other members of the clinical teamwork? Is security readily available from where you are seeing your patient? Even with more stable patients in clinic, positioning chairs so that you don’t block the patient from an exit can be helpful. Is there a safety code to text or call to staff to alert them if you are feeling unsafe?

Building Trust and Rapport

In addition to paying attention to physical safety, it’s important to develop your skills of self-observation and self-awareness in building trust with your patient. Have you had a difficult morning stuck in traffic and now feel agitated when you are meeting your patient? If you’re not aware of your own emotional valence, you may behave in a way that agitates your patient as well (for instance, excessive tapping of your foot or shaking your leg). Seamus Bhatt-Mackin, M.D., and Aaron Feiger, M.D., in their Handbook chapter, “Blue Ink and Blind Spots: Working Toward Accurate Self-Knowledge Through Self-Awareness,” suggest that practicing mindfulness techniques can help you observe your own emotional landscape and manage your stress so that it doesn’t leak into your interactions with your patient.

Taking a nonjudgmental stance toward your patient is another foundational aspect of building trust. Your patient is seeking care because of a mental health issue. Whether the patient’s life experience has been similar to yours or not, it’s important to remember that the patient needs your compassion and openness to share the personal information that will help both of you formulate an understanding of the patient’s psychiatric issues and collaborate on a treatment plan.

Approaching with curiosity and care and listening deeply with self-awareness will set you up well in building rapport with patients. Melanie Tervalon, M.D., in a seminal 1998 paper in the Journal of Healthcare for the Poor and Underserved titled “Cultural Humility Versus Cultural Competence,” emphasized that practicing the three principles of cultural humility can guide trainees in mindfully working with patients from marginalized communities: critical self-reflection (for example, recognizing one’s implicit bias); recognizing and changing power imbalances (for example, involving the patient in treatment planning), and advocating for institutional accountability.

Establishing Boundaries and Clear Communication

Maintaining clear and transparent boundaries is equally important in building trust with your patient. Clear communication about your role and the purpose of psychiatric treatment gives your patients an understanding of the work you are doing together. Your patients then have the opportunity to express their needs and thoughts within the known context of clinical care. For example, when patients are under an involuntary hold, communicating clearly what this means and when the hold expires gives them agency to manage their behaviors in their own best interest. In the outpatient setting, clear communication about a medication taper or side effects, for example, may allow patients to understand the benefits of following your recommendations.

Developing a Case Formulation

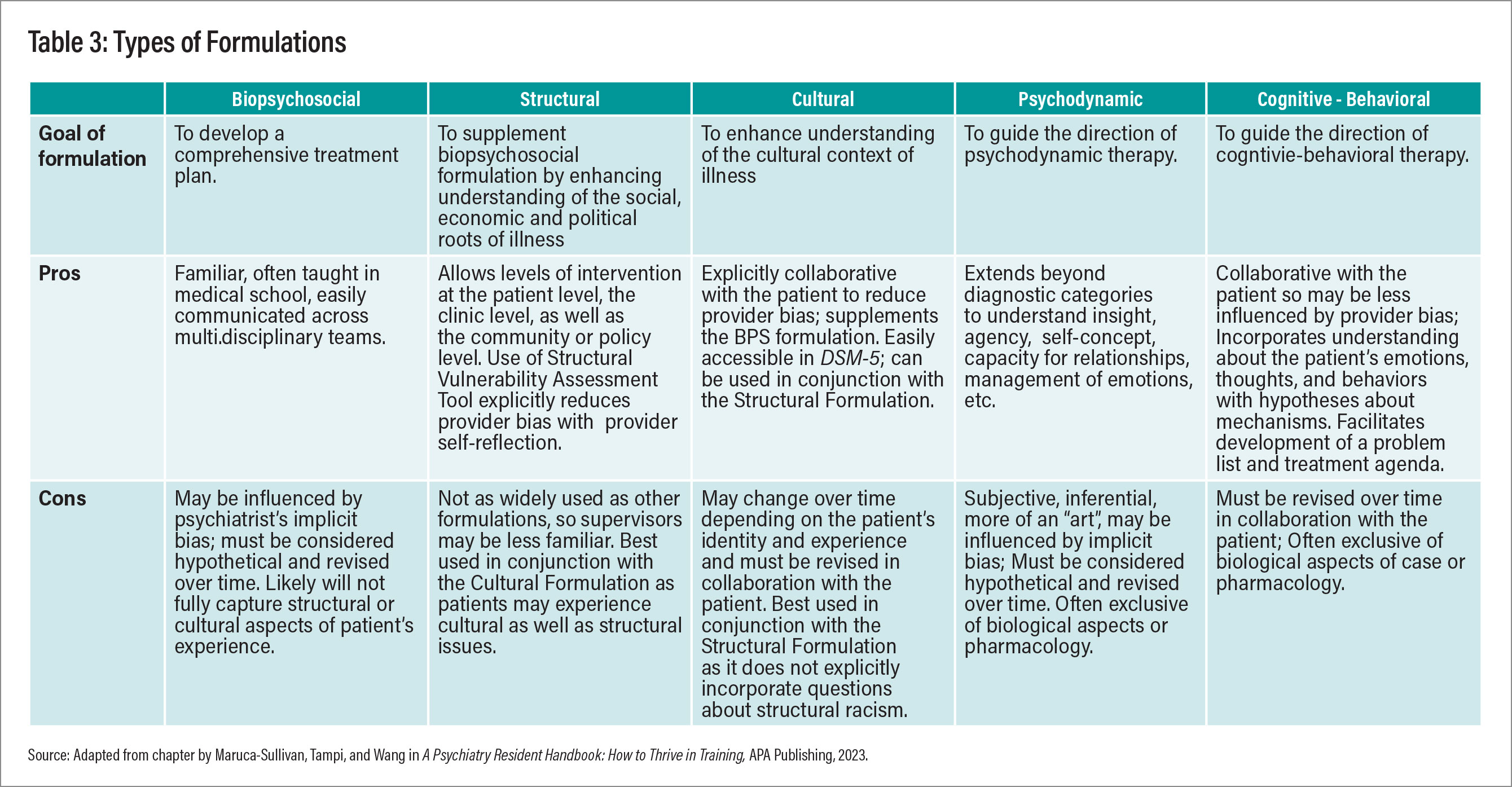

As you and your patient get to know one another, developing a case formulation or narrative hypothesis of your patient’s illness will inform your treatment approach. As the formulation evolves over time with integrating new patient information, it ensures you provide adequate care or choose effective approaches to address your patient’s suffering. Although challenging at first, developing a case formulation is an essential clinical skill.

A well-conceived biopsychosocial formulation of the patient provides scaffolding for your work together, but a comprehensive approach must also include an assessment of the cultural and structural factors that are part of your patient’s experience. DSM-5-TR defines cultures as “open, dynamic systems that undergo continuous change over time; in the contemporary world, most individuals and groups are exposed to multiple cultures, which they use to fashion their own identities and make sense of experience.” Integrating cultural formulation questions into a patient interview in a respectful, collaborative, and patient-oriented approach provides invaluable understanding as you develop your clinical hypotheses. You may have an opportunity to identify and address your own biases as well. However, a structural lens to case formulation is also essential and distinct from the cultural formulation. Structural formulations recognize the social policies, practices, and institutions that contribute to your patients’ illness, often creating disproportionate burdens on marginalized communities and resulting in health inequities. Examples of structural factors may include discrimination (racism, sexism, etc.), poverty, geographical and environmental inequities, and disparities in health care access. Jonathan Metzl, M.D., Ph.D., and Helena Hansen, M.D., Ph.D., noted in a 2018 article in JAMA Psychiatry titled “Structural Competence and Psychiatry” that a comprehensive structural formulation accounts for these factors and promotes both patient- and systems-level treatment interventions. Table 3 outlines the fundamental aspects of the biopsychosocial and complementary structural and cultural formulations. As psychiatry residents often recommend or engage patients in psychotherapy, fundamental aspects of psychodynamic and cognitive-behavioral therapy formulations are also included.

Making the Best Use of Supervision

All clinical work within training should be supervised directly, indirectly, or through oversight. Knowing how to effectively use supervision will enhance the development of your clinical and nonclinical skills during residency.

Supervision serves multiple clinical and training functions, ranging from promoting safe, effective patient care to providing essential skills for unsupervised practice and professional development. It is a relationship-based education and training that is work focused and manages, supports, develops, and evaluates the work of colleagues. Supervision in psychiatry residency is quite different from supervision in medical school or even in PGY-1 nonpsychiatry rotations. Depending on the venue and context, delays between making decisions and supervisory oversight may occur, increasing the need to prepare for and actively engage in supervision. Early on, you might feel dependent on supervisors for goal setting, overall guidance, and help with important clinical decisions. As you progress in training, you will become more able to identify supervision goals, including areas of knowledge or skill sets you want to refine before entering unsupervised clinical practice. A lot of what you learn in psychiatry occurs through supervision, so investing early in this relationship is pivotal!

Regular supervision involves learning not only about clinical issues at hand, but also how to work effectively with each patient as well as deal with important system issues. Supervisors are there to help support and guide trainees through difficult patient care scenarios. A good rule of thumb is that if at any time you wonder whether to talk to the supervisor, just do it!

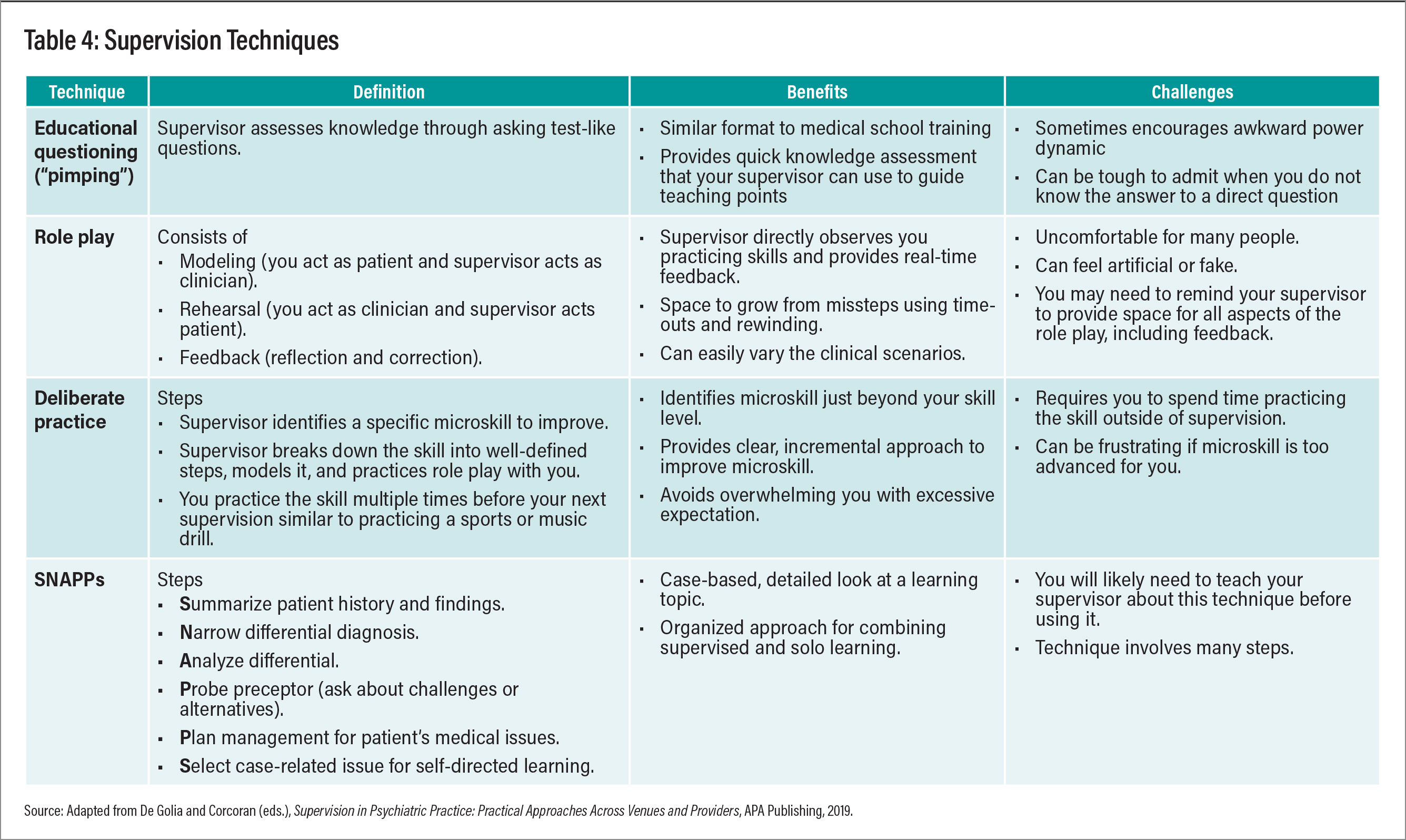

To get the most out of your supervision, come prepared—bring clinical questions, questions from the literature or didactics, inquiries about navigating the medical/legal system, or, if related to psychotherapy, video excerpts. Strive to be receptive to feedback, process countertransference as it may inform the formulation and could unintentionally interfere in the treatment process, and be cognizant of the boundary between supervision and personal psychotherapy. If you are uncomfortable sharing feelings with a supervisor or the emotions triggered by a patient affect your ability to intervene appropriately, consider starting or continuing individual psychotherapy. Supervision is not psychotherapy. Supervisors have their preferred supervision techniques. Advocate for the ones that best meet your learning style and goals but be open to trying new approaches (see Table 4).

Conclusion

Residency training in psychiatry involves enormous growth. Opening yourself to deeply understand another human being to mitigate pain and suffering is a remarkable journey unto itself. The residency process will change you—how you understand yourself, others, and the systems in which you work. This experience may often seem daunting, but by anticipating your developmental milestones and challenges, finding community, and securing mentorship, you can do more than just survive your training—you can thrive along the way. ■

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Culture and Diagnosis. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). Accessed March 20, 2024.

Barnes C, Lopez JD. The Psychiatric Emergency. In De Golia SG, Wang R (eds). A Psychiatry Resident Handbook: How to Thrive in Training, 1st Edition. American Psychiatric Association Publishing of Washington, D.C., April 2023

Bhatt-Mackin S and Feiger A. Blue Ink and Blind Spots: Working Toward Accurate Self-Knowledge Through Self-Awareness. In De Golia SG, Wang R (eds). A Psychiatry Resident Handbook: How to Thrive in Training, 1st Edition. American Psychiatric Association Publishing of Washington, D.C., April 2023

DeGolia SG, Wang R (eds). A Psychiatry Resident Handbook: How to Thrive in Training, 1st Edition. American Psychiatric Association Publishing of Washington, D.C., April 2023

DeGolia SG, Wang R. Framing the Residency Experience. In De Golia SG, Wang R (eds). A Psychiatry Resident Handbook: How to Thrive in Training, 1st Edition. American Psychiatric Association Publishing of Washington, D.C., April 2023

De Golia SG: Elements of Supervision, in Supervision in Psychiatric Practice: Practical Approaches Across Venues and Providers. Edited by De Golia SG, Corcoran KM. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2019, p 3-24

DeGolia SG, Corcoran KM (eds). Supervision in Psychiatric Practice: Practical Approaches Across Venues and Providers. American Psychiatric Association Publishing, WDC. April 2019.

Edwards M, Polignano M. Centering Our Identities. In De Golia SG, Wang R (eds). A Psychiatry Resident Handbook: How to Thrive in Training, 1st Edition. American Psychiatric Association Publishing of Washington, D.C., April 2023

Haghighat N, Vo P, Reddy H, Cooper T. Best Practices in Prescribing Medications. In De Golia SG, Wang R (eds). A Psychiatry Resident Handbook: How to Thrive in Training, 1st Edition. American Psychiatric Association Publishing of Washington, D.C., April 2023

Khan MM, Goetz TG, Erickson-Schroth L. Gender and Sexual Identity. In De Golia SG, Wang R (eds). A Psychiatry Resident Handbook: How to Thrive in Training, 1st Edition. American Psychiatric Association Publishing of Washington, D.C., April 2023

Maruca-Sullivan P, Tampi R, Wang R. Learning to Develop a Case Formulation. In De Golia SG, Wang R (eds). A Psychiatry Resident Handbook: How to Thrive in Training, 1st Edition. American Psychiatric Association Publishing of Washington, D.C., April 2023

Metzl JM, Hansen H: Structural Competency and Psychiatry. JAMA Psychiatry 75(2):115–116, 2018

Milne DL: Evidence-Based Clinical Supervision: Principles and Practice. Malden, MA, BPS/Blackwell, 2009

Palermo D, Guthrie T. The Underrepresented in Medicine Experience. In De Golia SG, Wang R (eds). A Psychiatry Resident Handbook: How to Thrive in Training, 1st Edition. American Psychiatric Association Publishing of Washington, D.C., April 2023

Thomas L and Sadhu M. Mentorship and Sponsorship. In De Golia SG, Wang R (eds). A Psychiatry Resident Handbook: How to Thrive in Training, 1st Edition. American Psychiatric Association Publishing of Washington, D.C., April 2023

Watkins CE, Callahan JL. Psychotherapy Supervision Research: A Status Report and Proposed Model, in Supervision in Psychiatric Practice: Practical Approaches Across Venues and Providers. Edited by De Golia SG, Corcoran KM. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2019, p 25-34

M. Tervalon, J. Murray-Garcia (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education, Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, Vol. 9, No. 2. (May 1998), pp. 117-125

Bourgois P, Holmes SM, Sue K, et al: Structural vulnerability: operationalizing the concept to address health disparities in clinical care. Acad Med 92(3):299–307, 2017 27415443

Jacqueline BP, Lisa ST: Developing and using a case formulation to guide cognitive-behavior therapy. J Psychol Psychother 5(3):179, 2015

McWilliams N: Psychoanalytic Diagnosis: Understanding Personality Structure in the Clinical Process. New York, Guilford, 2011