Access to In-Network Mental Health Care Still Lags Far Behind Other Medical Care

Abstract

A downstream effect of insurers not complying with parity laws is that patients who seek mental health care must go out of network to find it.

When the Mental Health and Addictions Equity Act final regulations went into effect in 2011, they required that reimbursement rates for behavioral health be comparable to and no more stringent than for medical care. Thirteen years later many insurers have yet to meet that requirement and still do not pay mental health professionals on par with other health professionals.

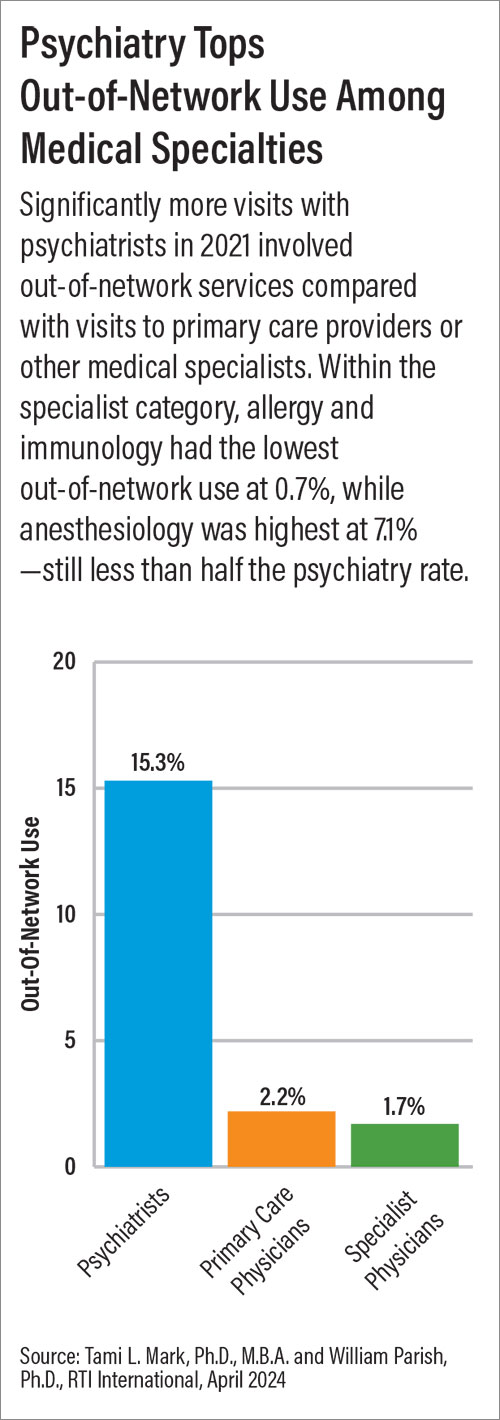

Now a report by RTI International illuminates a downstream effect of this noncompliance: Insured patients who seek mental health care often go out of network to find it, mainly because inappropriate reimbursement discourages mental health professionals from participating in health plans. Between 2019 and 2021, patients went out of network 3.5 times more often to see a behavioral health professional (physician or nonphysician) than to see a medical or surgical professional. Patients went out of network 8.9 times more often to see a psychiatrist than another specialty physician, and 6.9 times more often to see a psychiatrist than a primary care physician.

“High out-of-network use is a consequence of health plans contracting with too few providers,” health economist and lead author Tami Mark, Ph.D., M.B.A., told Psychiatric News. She is a distinguished fellow and director of behavioral health financing and quality measurement at RTI International. “Health plans are not using their key lever to encourage psychiatrists to participate in-network: reimbursement rates.”

In research partially funded by APA, Mark and fellow RTI health economist William Parish, Ph.D., M.A., analyzed enrollment data and claims from more than 22 million individuals captured annually from 2019 through 2021 to evaluate out-of-network use and reimbursement rates across all 50 states. They found that the average reimbursement for all medical/surgical clinician office visits was 21.7% higher than for all behavioral health clinicians. The average reimbursement for medical/surgical specialist physician office visits was 24.9% higher than for psychiatrist office visits. Notably, the average reimbursement for physician assistant office visits was 18.7% higher than for psychiatrists, and the average reimbursement for a nurse practitioner office visit was 8.2% higher than for psychiatrists.

Psychiatrists must advocate for eliminating disparities in reimbursement, said Tami Mark, Ph.D.

Such disparities in reimbursement serve as a deterrent to psychiatrist participation in networks, said Robert Trestman, M.D., Ph.D., who was not involved in the research. Trestman is chair of APA’s Council on Healthcare Systems and Financing and professor and chair of psychiatry and behavioral medicine at the Carilion Clinic and the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine.

“The reality is that after medical school and residency, most psychiatrists have $200,000 to $300,000 of debt,” Trestman said. “We have chosen careers that allow us to exercise both our expertise and compassion and love for caring for other people, but like everyone else, we have to pay our bills.

“We want to be altruistic, and most of us do have sliding scales even if we don’t deal with insurance, but the cost of care delivery continues to go up, including rent, malpractice insurance, and the administrative overhead required by all the regulatory agencies,” he added.

From the patient’s perspective, barriers to care arise when there are few mental health professionals in network or the wait time for an in-network appointment is very long, especially if the patient cannot afford to pay the higher out-of-network copayments or out of pocket. In the end, patients may decide they cannot afford mental health care at all.

“This is exactly the cynical approach that many insurers have taken,” Trestman said. “As for-profit organizations they are focused on making money for their investors, and they have created a situation where the [financial] burden [for mental health care] falls on the patients.”

There must be financial penalties for insurers who do not comply with parity laws, said Robert Trestman, M.D., Ph.D.

He added that insurers must face consequences for not complying with the law.

“The only language insurers use is financial, so there must be financial penalties for not having adequate reimbursement so that psychiatrists are willing and able to participate [in health plans],” Trestman said.

“The report’s findings make it clear that health insurers must be held accountable for not complying with the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act and provide appropriate payment for the care offered by psychiatrists and other mental health professionals,” said Saul Levin, M.D., M.P.A., who was APA CEO and medical director as Psychiatric News went to press. “Enforcing parity will increase participation in insurance plans among mental health professionals and therefore increase access to mental health care by making those services more affordable for patients.”

Plan for Action

Mark put the onus for change not on patients, but the authorities.

“Clearly states, federal agencies, and employers as insurance purchasers and fiduciaries for their employees need to do more to hold health plans accountable for providing equal access to psychiatric services,” she said.

The researchers recommended that federal and state agencies develop standardized templates to identify and remedy parity violations. They outlined several methods for developing these templates, including the following:

Comparing behavioral health and medical/surgical reimbursement rates using Medicare benchmarks to allow valid and accurate comparisons across the array of services.

Evaluating reimbursement disparities by specific provider type.

Using all procedure billing codes when evaluating out-of-network use and reimbursement disparities, and not just a few selected codes.

In the meantime, psychiatrists can advocate on behalf of their patients and themselves.

Enforcing parity will increase mental health professionals’ participation in insurance plans, said Saul Levin, M.D., M.P.A.

“We need to continue to advocate effectively and vocally by building coalitions with NAMI [the National Alliance on Mental Illness] and other advocacy organizations that represent patients and their families, as well as other national professional associations such as the American Medical Association, the American Psychological Association, and the American Hospital Association, who jointly continue to meet with our legislators to push forward changes in the law,” said Trestman.

Changes that have been implemented since the Mental Health and Addiction Equity Act went into effect demonstrate that compliance with the law is possible, and there is no time like the present for psychiatrists to get involved.

“Before the Mental Health and Addiction Equity Act, most patients faced limits on outpatient visits and the length of inpatient stays, and patients had higher co-insurance for psychiatric treatment, as described in their benefits. The parity law eliminated those obvious disparities,” said Mark. “Psychiatrists need to advocate for similar transparency regarding other types of disparities such as out-of-network use, patients’ out-of-pocket spending, psychiatrist network participation standards, and the application of prior authorization.

“Advocating for eliminating these disparities will help patients obtain needed, affordable psychiatric care. The COVID-19 pandemic heightened legislators’ awareness of mental health disorders so now is the time to advocate for mental health parity,” she added.

The report was commissioned by the Mental Health Treatment and Research Institute, a tax-exempt subsidiary of The Bowman Family Foundation. A portion of the cost of the report was funded by the American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association, and the National Association for Behavioral Healthcare. ■