Special Report: Integrative Medicine in Psychiatry: Beyond Just Treating the Disease

Abstract

The need for integrative medicine arises from a growing recognition of the benefits for a holistic approach to health care as well as a burgeoning desire by the public to take charge of their health and well-being by adopting new practices.

In comparison with general medicine, the field of psychiatry is unique in a few important areas. First, the treatments for most psychiatric conditions are usually not curative and are more often meant to ameliorate symptoms associated with a condition. Why is this? It is virtually impossible to find a medical or psychiatric cure if the pathogenesis for a disorder is unknown. Indeed, the cause or clear contributory factors associated with most psychiatric conditions remain a mystery.

The second unfortunate distinguishing feature among those with severe and chronic emotional distress is suboptimal access to care, with related increased overall morbidity and mortality. For example, those with persistent and severe mental illness are likely to die 15 to 20 years earlier relative to the general population. They are more likely to have debilitating and chronic nonpsychiatric illnesses, such as diabetes, hypertension, some cancers, and infectious diseases. Those with severe psychiatric disorders are less likely to receive preventive care or early-stage medical intervention.

Integrative medicine is an important clinical tool for psychiatrists to incorporate into their practice, with a strong focus on prevention, early intervention, and, when possible, identification of the underlying or root cause for ongoing emotional distress. Additionally, incorporation of integrative and preventive psychiatric medicine into primary care and behavioral health care settings indirectly expands behavioral health access by promoting wellness and decreasing the need for psychiatric specialty care referrals.

Integrative medicine combines conventional Western medicine with alternative approaches to care, such as herbal remedies, use of evidence-based supplements, acupuncture, massage, mindfulness, yoga, biofeedback, stress reduction techniques, and motivational interviewing, among others. The need for integrative medicine arises from a growing recognition of the benefits for a holistic approach to health care. Here are some reasons why integrative medicine is integral to the fields of psychiatry and general medicine:

Emphasis on prevention and early-stage intervention: Integrative medicine stresses the importance of evidence-informed lifestyle and preventive measures to reduce the risk of developing or worsening existing chronic diseases. This proactive approach to health and wellness puts less emphasis on treating an advanced disease and can be routinely used by psychiatrists, while leading to better long-term outcomes.

Whole-person care: Integrative medicine emphasizes treating the whole person—mind, body, and spirit—rather than just focusing on the disease or symptoms. This approach acknowledges the complex and often unknown interactions between different aspects of a person’s health.

Personalized medicine: Each individual is unique and therefore requires a personalized treatment plan. What works for one person may not work for another, even if both have the same condition. We see this frequently when using traditional treatments for depressive, anxiety, psychotic, and other common psychiatric disorders.

Patient-directed motivation and empowerment: Patients are encouraged to take an active role in their health and related decisions. By leading the approach to their care and utilizing a team-based approach with the medical team, patients are more likely to benefit from treatment plans and make lifestyle changes that support their well-being. Put another way, if the treatment plan is mainly generated from a patient and not a physician, there is a higher chance for sustained motivation to change and improve health.

Addressing root or underlying causes: Rather than just treating symptoms, integrative medicine seeks to identify and address the root causes of health issues. This can lead to more effective and long-lasting solutions.

Filling gaps in conventional medicine: Some conditions, such as chronic pain, depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, insomnia, or fatigue, might not be adequately addressed or fully explained by conventional medicine alone. Integrative medicine offers additional options and support for managing these often-complex conditions.

Supporting the patient: For individuals undergoing treatment for serious conditions like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or increased risk for self-harm or suicide, integrative therapies can provide supportive care to help manage side effects, improve quality of life, and enhance overall well-being.

The need for integrative medicine continues to grow as more people seek out personalized, whole-person approaches to care that consider their full spectrum of needs, values, and health goals. The global market for integrative health and medicine has been expanding in recent years. A report by Grand View Research shows this market size was valued at $82.27 billion in 2020 and is expected to expand at a compound annual growth rate of 22% from 2021 to 2028. This growth showcases the increasing patient interest and the broader acceptance of integrative medicine practices. The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), part of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, has shown that a significant portion of the U.S. population uses integrative health approaches. For example, its 2017 survey found that 33.2% of Americans used integrative health approaches, such as use of supplements, acupuncture, chiropractic care, meditation, or other treatment modalities.

Practical Integrative Psychiatry Pointers

Movement and Exercise

Sedentary behavior, defined as any waking behavior characterized by an energy expenditure of ≤1.5 metabolic equivalents (METs) while in a sitting, reclining, or lying posture, is becoming increasingly prevalent due to changes in work, home, and leisure activities and environments. Sedentary behavior can negatively impact mental and physical health. Decreased movement and physical activity are risk factors for the development or worsening of depression, anxiety, stress, cognitive function, and sleep dysregulation. When used as an independent treatment for depression, exercise showed a 58% reduction in symptoms of major depression, more than double that of the placebo group (22% improvement). Social isolation and obesity are both correlated with suboptimal exercise regimens and can also worsen self-esteem and overall mental health.

Adults should aim for at least 150 minutes a week of moderate-intensity exercise (for example, brisk walking, biking, swimming), or 75 minutes a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity (jogging, running, biking on elevated terrain, fast-paced sports activities). Muscle strengthening activities at least twice a week are recommended. Those between the ages of 6 and 17 should exercise for at least one-hour a day.

Patients who are new to exercise or struggle to maintain a routine exercise schedule should work with the clinician to help develop a movement plan. This plan should be realistic and start at a lower level of duration and intensity, while building up slowly and reliably. Clinicians should assess the level of patient motivation and co-develop a plan accordingly.

Restorative sleep

Sleep has an important role in maintaining brain homeostasis, neuroplasticity, cognition, emotional regulation, and overall behavioral health. Sleep disorders affect up to 70 million adults in the United States, and approximately 80% of patients experience insomnia while in the acute phase of a mental health episode. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends at least seven hours of sleep for adults.

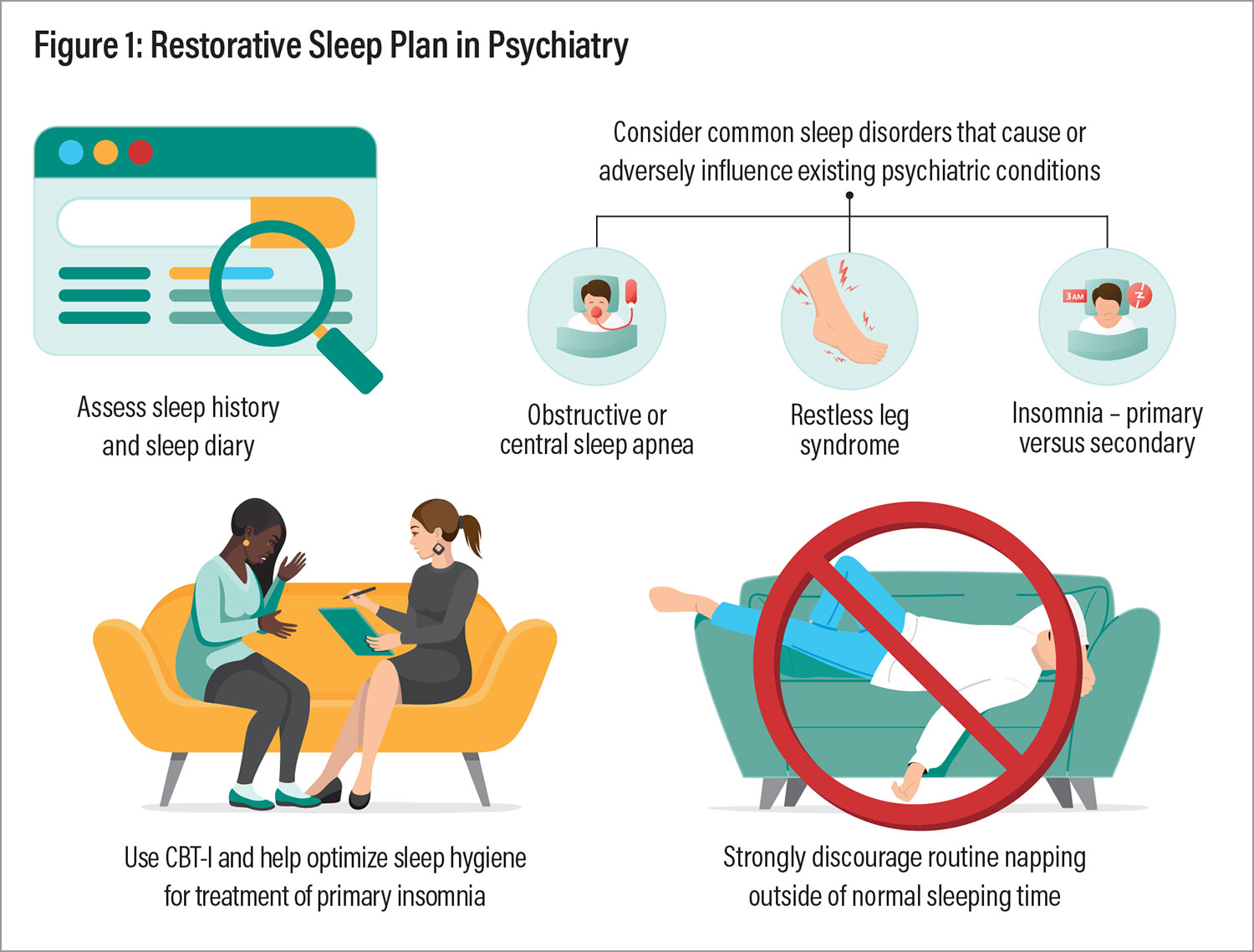

Insomnia is defined as the inability to fall or stay asleep for at least three nights a week, while a chronic diagnostic specifier indicates this condition is ongoing beyond three consecutive months. It is important to exclude medical causes of insomnia, which may include anxiety, depression, psychosis, substance use disorder, obstructive or central sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movement disorder, chronic pain, and metabolic conditions, among others.

Once secondary medical causes are excluded, the first-line treatment of primary insomnia includes incorporation of sleep hygiene and utilization of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I). CBT-I combines cognitive therapy strategies with education about sleep regulation and hygiene, with additional focus on relaxation techniques, recognizing positive associations with the sleeping environment, and sleep restriction. Treatment usually involves six to eight sessions with a behavioral sleep medicine practitioner and the assessment of information gathered by the patient in the form of a sleep diary.

Figure 1: Restorative Sleep Plan in Psychiatry

Sleep hygiene is an important component of CBT-I and should be part of the treatment plan for those struggling with insomnia. The essentials of sleep hygiene include educating patients about normal or restorative sleep architecture, while discussing specific behaviors that negatively impact sleep. This includes avoiding caffeine and alcohol; engaging in moderate intensity physical activity (not immediately before bedtime); avoiding blue light exposure in the evening; and keeping the bedroom dark, quiet, and cool. Patients should be strongly encouraged to not take naps outside of the normal sleep cycle. (see Figure 1).

Food as Medicine and Supplements

The connection between food, supplements, and behavioral health is an area of growing research interest, exploring how specific dietary patterns and nutrient intakes can positively influence mental well-being.

Balanced diet

Diets high in processed, preserved, and high-sugar foods have been linked to elevated risks of depression and anxiety, among other medical illness. These types of food also have more potential to create a dangerous pro-inflammatory state. In contrast, diets emphasizing whole foods, such as the Mediterranean diet, have been associated with a lower risk of mental disorders. This diet focuses on fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fish, olive oil, and moderate wine consumption. Studies show moderation and balance are most important with healthy eating. Relative excess with any of the macronutrients, over an extended period, is not recommended.

Omega-3 fatty acids

Omega-3 fatty acids (OFA-3s) are essential fats, meaning the body cannot naturally produce them, and they must be obtained through diet. OFA-3s are needed to optimize cellular function, cardiovascular health, brain function, and inflammation control. There are three main types of OFA-3s: alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA).

OFA-3s, particularly EPA and DHA, are found naturally in salmon, mackerel, sardines, and algae oils. Many people are deficient in OFA-3s and, as a result, may suffer from anxiety, depression, and cognitive decline. This potential connection is grounded in the role of OFA-3s to enhance brain function by way of anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties.

In addition to lowering triglycerides and blood pressure, OFA-3s can also decrease the potential for atherosclerosis in those at risk for heart disease, including people with schizophrenia or those who take certain antipsychotic medications. OFA-3s may decrease the severity and duration of anxiety and depressive episodes, while protecting against cognitive decline.

The American Heart Association recommends eating at least two servings of fatty fish a week for heart health and to obtain adequate amounts of EPA and DHA. If this diet cannot be maintained, at least 1 gram of EPA+DHA, with a higher proportion of EPA, may be used as a supplement for the treatment of depression. Some studies suggest that doses between 2 to 3 grams of EPA+DHA daily may be more effective for the treatment of severe depression, particularly with a higher ratio of EPA.

Magnesium

Magnesium plays a crucial role in brain function and mood regulation, with deficiencies specifically linked to an increased risk of anxiety. Some studies suggest magnesium supplementation can improve symptoms of depression and anxiety, as an adjunct to other treatment modalities. The recommended dietary allowances (RDAs) for magnesium for adult men are 400 mg to 420 mg a day and for adult women, 310 mg to 320 mg a day. A diet rich in leafy vegetables, nuts, seeds, legumes, and whole grains should provide a healthy amount of magnesium.

Vitamin D

Observational studies have found an association between low levels of vitamin D in the blood and an increased risk of depression. Vitamin D not only is essential for bone health and immune function but also plays a role in brain development and monoamine neurotransmitter regulation and serves as an anti-inflammatory agent. People with low serum 25 (OH)D levels should be considered for replacement therapy. D3 supplements may be used at a conservative dosing range of 800 IU to 1000 IU or 20 mcg to 25 mcg a day. If the serum level is <12 ng/ml, higher doses may be considered, and malabsorption and routine inactivity with limited sun exposure should be considered and addressed, as indicated.

Gut/brain axis

The gut-brain axis is a complex communication network that links the gastrointestinal tract and the brain. A key component of this axis is the gut microbiome, or the collective grouping of microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other entities that reside in the digestive tract. The gut microbiome plays a significant role in brain health, while having an effect on mood, cognition, and susceptibility to neurological disorders. Microbiome diversity, or lack thereof, as well as overabundance of certain microbial species has been linked to various mental disorders, such as anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.

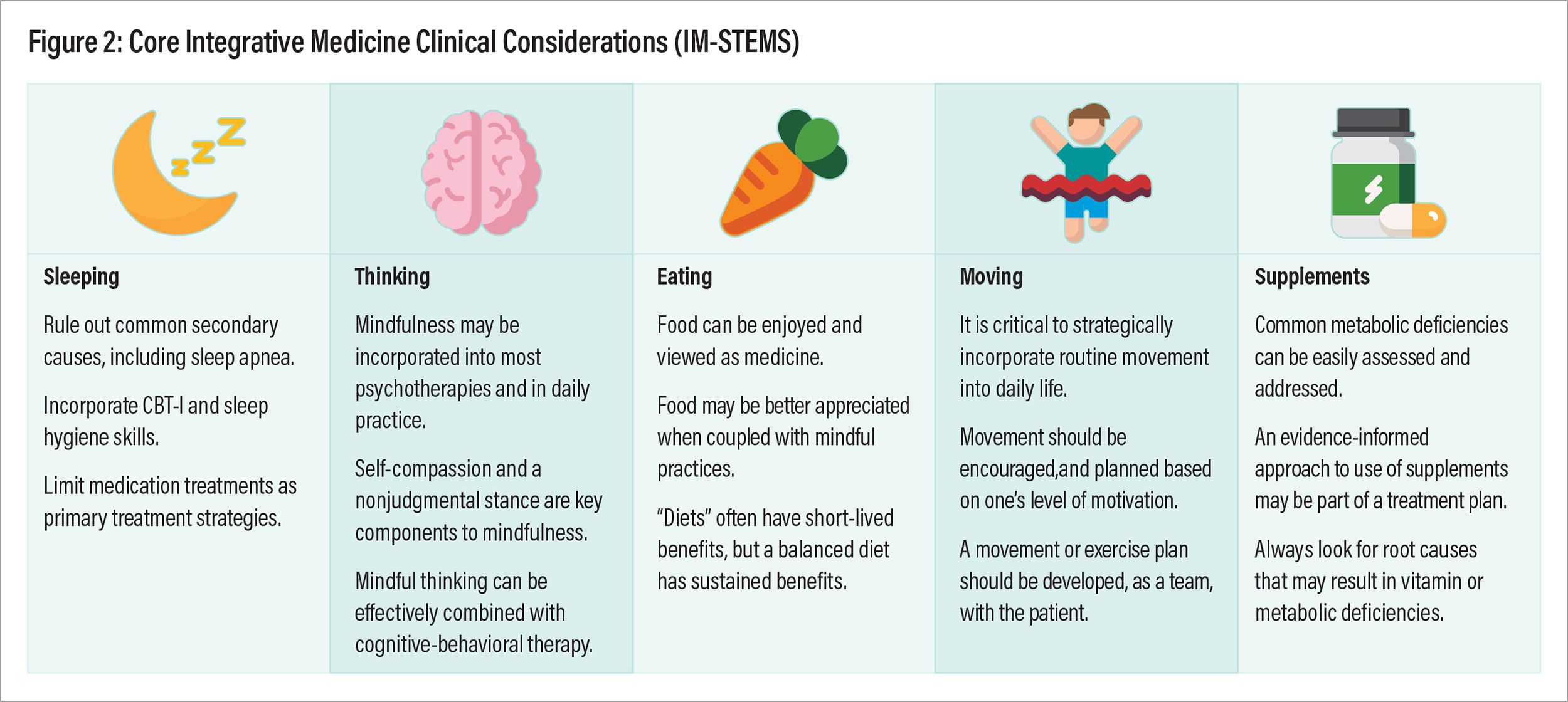

Figure 2: Core Integrative Medicine Clinical Considerations (IM-STEMS)

The gut-brain microbiome axis plays a critical role in the overall function of the immune system. A pro-inflammatory state can influence brain function and is implicated in several psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases (for example, depression and anxiety). The gut microbiome plays a role in modulating immune responses, which affects emotion. The gut microbiome not only influences the production of monoamine neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, which may cause fluctuations in mood or emotion, but also produces neuroactive compounds by producing short chain fatty acids and regulating the taurine and cortisol metabolism pathways. An altered gut microbiome has been linked to increased permeability of the blood-brain barrier, which is associated with several neurological and psychiatric conditions, including depression, anxiety, and cognitive slowing, among others.

Probiotics are live microorganisms that may address an unhealthy gut microbiome. They can help restore or maintain a healthy gut microbiota composition, which, in turn, may positively affect the gut-brain axis. Probiotics have been studied in the context of mental health disorders, such as anxiety and depression, with some promising but mixed results. A balanced diet plays a crucial role in maintaining a balanced gut microbiome. Diets rich in fiber, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fresh yogurt, and fermented foods can promote and accelerate the growth of beneficial gut bacteria. The Mediterranean diet, in particular, has been associated with benefits to both the gut microbiome and mental health.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a mental practice that uses meditation and breathing techniques to help the patient pay full attention to the present moment—the here and now—with an attitude of nonjudgmental awareness and self-compassion. The key aspects of mindfulness involve being aware of one’s thoughts, emotions, bodily sensations, and the surrounding environment without trying to change or judge them. All of this is done in lieu of focus or contemplation on existing negative thoughts or emotions, such as depression, anger, or anxiety. Mindfulness may be used to treat psychiatric conditions and comes in various forms, including mindfulness-based stress reduction, and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR)

MBSR helps people focus on positive or neutral stimuli instead of negative emotions or situations. This brings the patient to a state of calmness and reduced stress. MBSR combines mindfulness meditation and yoga in a group psychotherapeutic setting to address a broad array of health problems, including stress, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and chronic pain. A typical program is relatively brief, only eight to ten sessions over the course of several weeks. Group participants discuss their experiences on a weekly basis and also complete about 45 to 60 minutes of independent study each day.

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT)

MBCT is a structured, brief, group-based program designed to prevent the recurrence of depressive episodes, particularly in individuals who have experienced one or more episodes of major depression. It combines the principles of cognitive therapy with meditative practices and attitudes based on the cultivation of mindfulness. The core premise behind MBCT is to acknowledge the challenge of directly changing a negative emotion, and instead work toward finding and reconstructing inaccurate thinking, which is closely linked to the emotion. This approach is comingled with the use of group-based mindfulness techniques.

Similar to MBSR, MBCT is typically delivered in a group format over eight weeks, with weekly sessions and daily “homework” assignments. MBCT has been most extensively researched for its effectiveness in reducing the risk of relapse in individuals with recurrent major depressive disorder. Studies have shown it to be as effective as first-line antidepressant medications in preventing major depressive episode relapse.

The UCI Susan Samueli Integrative Health Institute Integrative & Functional Medicine Fellowship prepares physicians to deliver evidence-informed integrative, personalized whole-person care. More information here.

Final Thoughts

The practice of psychiatry includes part “science,” part “art of medicine,” and an authentic partnership with our patients toward better health. Understanding how to incorporate evidence-informed integrative medicine approaches to care, while we continue our career-long search for the root cause of psychiatric disorders, will help our patients recover quicker and more fully (see Figure 2). Discussing the importance of wellness—in place of disease—with our patients can be therapeutic in itself. For example, discussing treatments to advance “happiness” with a patient who is struggling with depression may be forward thinking and more goal directed. Redirecting thoughts and real-time focus with mindfulness techniques can be an added feature to traditional psychotherapy. Psychiatrists can encourage lifestyle changes to improve health and promote wellness among their patients. ■

Resources

Investigating Nutrient Biomarkers of Healthy Brain Aging: A Multimodal Brain Imaging Study

Social Determinants of Health and Diabetes: A Scientific Review

Access to Specialty Healthcarein Urban Versus Rural US Populations: A Systematic Literature Review

Integrative Medicine Therapies for Pain Management in Cancer Patients

Sleep, Insomnia and Mental Health

Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Sleep Hygiene

Sleep Duration and Health in Adults: An Overview of Systematic Reviews

Exercise Interventions for the Prevention of Depression: A Systematic Review of Meta-Analyses

The Effects and Mechanisms of Exercise on the Treatment of Depression. Front Psychiatry

A Randomised Controlled Trial of Dietary Improvement for Adults With Major Depression

The Role of Diet and Nutrition on Mental Health and Wellbeing

Dietary Recommendations for the Prevention of Depression

Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Mental Health

The Role of Magnesium in Neurological Disorders

Vitamin D and the Brain: Genomic and Non-genomic Actions

Mindfulness-Based Interventions: An Overall Review